Vogtle-4 reaches testing milestone

Cold hydro testing of Unit 4 at the Vogtle plant’s nuclear expansion site has been completed, Georgia Power announced on December 7.

Published since 1959, Nuclear News is recognized worldwide as the flagship trade publication for the nuclear community. News reports cover plant operations, maintenance and security; policy and legislation; international developments; waste management and fuel; and business and contract award news.

A message from Goodway Technologies

Optimizing Maintenance Strategies in Power Generation: Embracing Predictive and Preventive Approaches

Cold hydro testing of Unit 4 at the Vogtle plant’s nuclear expansion site has been completed, Georgia Power announced on December 7.

Nuclear Newswire is back with the final #ThrowbackThursday post honoring the 80th anniversary of Chicago Pile-1 with offerings from past issues of Nuclear News. On November 17, we took a look at the lead-up to the first controlled nuclear chain reaction and on December 1, the events of December 2, 1942, the day a self-sustaining nuclear fission reaction was created and controlled inside a pile of graphite and uranium assembled on a squash court at the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field.

The Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Energy announced December 7 that its new HALEU Consortium is open for membership. And not just from U.S. enrichers, fuel fabricators, and others working in the front-end fuel cycle, but from “any U.S. entity, association, and government organization involved in the nuclear fuel cycle,” and—at the DOE’s discretion—“organizations whose facilities are in ally or partner nations.” The HALEU Consortium will essentially serve as an information clearinghouse to meet DOE-NE’s ongoing needs for firm supply and demand data as it supports the development of a commercial domestic high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) infrastructure to fuel advanced reactors. The consortium is open for business almost one full year after the DOE first requested public input on its structure.

.jpg)

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has docketed Vistra Corporation’s license renewal application for the Comanche Peak reactors.

Operated by Vistra subsidiary Luminant and located in Glen Rose, Texas, the Comanche Peak plant is home to two pressurized water reactors. The original 40-year licenses for Units 1 and 2 expire in February 2030 and February 2033, respectively.

Steven Arndt

president@ans.org

For years the U.S. nuclear industry has done an outstanding job keeping plant availability high while simultaneously continuing to improve safety and economics. With capacity factors averaging more than 90 percent, you would think that no one would shut down an operational nuclear power plant. But that is what we have seen in a number of cases. Fortunately, this now seems to be changing. As I write this column, Diablo Canyon’s new life extension application has just been submitted to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission for review, and the Department of Energy’s program to support continued operation of nuclear power plants is providing hope that current plants will continue to have the opportunity to demonstrate their operational excellence.

How did we get here? When I ask this question—both of myself and the industry as a whole—I envision this as two sides of the same coin. Through the efforts of many we have improved our financial and economic viability, but challenges remain because the full value proposition of nuclear energy has not been realized.

The British government has announced an investment of £679 million (about $828 million) in the proposed Sizewell C nuclear plant in Suffolk, England, confirming chancellor of the exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s remarks on the project in his November 17 Autumn Statement.

The Ontario government has announced the start of site preparation at the Darlington nuclear power plant for Canada’s first grid-scale small modular reactor: GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy’s (GEH) BWRX-300.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Office of Regulatory Research recently awarded 20 new research and development grants in the University Nuclear Leadership Program (UNLP). The grants, totaling $9,998,188, are derived from the $16 million that Congress appropriated for the program for fiscal year 2022. The 20 selected proposals were among the 89 that were submitted to the NRC and peer-reviewed by the commission staff and experts from academia.

A Westinghouse-Bechtel team, France’s EDF, and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power have all submitted their initial bids for securing the contract to build a fifth reactor at the Czech Republic’s Dukovany plant, Czech utility ČEZ has announced.

Centrus Energy confirmed on December 1 that its wholly owned subsidiary American Centrifuge Operating signed a contract with the Department of Energy, which was first announced on November 10, to complete and operate a demo-scale high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) gaseous centrifuge cascade.

.png)

NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes has completed construction and all equipment installation at its new facility in Beloit, Wis., to produce the medical radioisotope molybdenum-99 without the use of high-enriched uranium, the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration announced last week.

The ITER Organization is working on a new baseline schedule for the magnetic confinement fusion experiment launched in 1985 and now under construction in southern France. First plasma was scheduled for December 2025 and deuterium-tritium operations for 2035 under a schedule approved in November 2016 that will soon be shelved. In addition to impacts from COVID-19 delays and uncertainty resulting from Russia’s war in Ukraine, ITER leaders must now factor in repair time for “component challenges.”

Westinghouse Electric Company has announced the signing of a long-term technology license agreement with Swedish engineering services firm Studsvik to develop a metals recycling and treatment facility at Westinghouse’s Springfields site.

Located near Preston, Lancashire, in northwestern England, Springfields is the United Kingdom’s only site for nuclear fuel manufacturing, supplying all its advanced gas-cooled reactor fuel. According to Westinghouse, Springfields fuel is responsible for about 32 percent of Britain’s low-carbon electricity generation. In addition, the site exports other nuclear fuel products to customers around the globe.

Craig Piercy

cpiercy@ans.org

It’s always the first question asked. So, what is your approach? You have options.

You could go the “Yucca Mountain is the law of the land” route. But you’ll soon run into an immutable political truth. Nevada’s early presidential caucuses make it highly unlikely that any candidate would ever take a favorable position on Yucca unless it enjoyed commensurate support in the state. Not convinced? Nevada Gov. Stephen Sisolak signed a bill in August that replaces their closed caucus system with a primary during the first week in February, thereby putting the state in competition with Iowa and New Hampshire to be the “first primary” of the 2024 election. Face it: While you weren’t looking, Nevada secured its consent rights over Yucca Mountain; it’s just written in a different part of the law.

You could also double down on reprocessing/recycling and argue that we need some sort of Manhattan Project. But that requires convincing Congress that it’s a good idea for the government to build large, first-of-a-kind, multibillion-dollar fuel cycle facilities, the economics of which will be based on the estimated price of uranium (or thorium?) some number of decades from now. Good luck with that. As much as a grand solution to the fuel cycle may appeal to our engineering instincts, the funding simply isn’t there—there are no checks left in Washington’s checkbook.

Mobile unmanned systems, also known as MUS, encompass a range of robotic devices, including drones, ground vehicles, crawlers, and submersibles. They are used for a wide range of industrial and defense applications to automate operations and assist humans or completely remove human workers from hazardous conditions. Robotics are ubiquitous in industrial manufacturing. Military robots are routinely employed in combat support applications, such as reconnaissance, inspection, explosive ordnance disposal, and transportation. Drones are used in many industries for security and monitoring, to conduct aerial inspections or surveys, and to capture digital twins. Wind and solar farms use MUS technologies for day-to-day operations and maintenance.

The question of what to do with the radioactive waste has been raised frequently for both fission and fusion. In the 1970s, fusion adopted the land-based disposal option, primarily based on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s decision to regulate all radioactive wastes as only a disposal issue, following the fission guidelines. In the early 2000s, members of the Advanced Research Innovation and Evaluation Study (ARIES) national team became increasingly aware of the high amount of mildly radioactive materials that 1-GWe fusion power plants will generate, compared with the current line of fission reactors. The main concern is that such a sizable inventory of mostly tritiated radioactive materials would tend to rapidly fill U.S. repositories—a serious issue that was overlooked in early fusion studies1 that could influence the public acceptability of fusion energy and will certainly become more significant in the immediate future if left unaddressed, as fusion moves toward commercialization.

Whether commercial demand for high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) fuel ultimately falls at the high or low end of divergent forecasts, one thing is certain: the United States is not ready to meet demand, because it currently has no domestic HALEU enrichment capacity. But conversations happening now could help build the commercial HALEU enrichment infrastructure needed to support advanced reactor deployments. At the 2022 American Nuclear Society Winter Meeting, representatives from three potential HALEU enrichers, the government, and industry met to discuss their timelines and challenges during “Got Fuel? Progress Toward Establishing a Domestic US HALEU Supply,” a November 15 executive session cosponsored by the Nuclear Nonproliferation Policy Division and the Fuel Cycle and Waste Management Division.

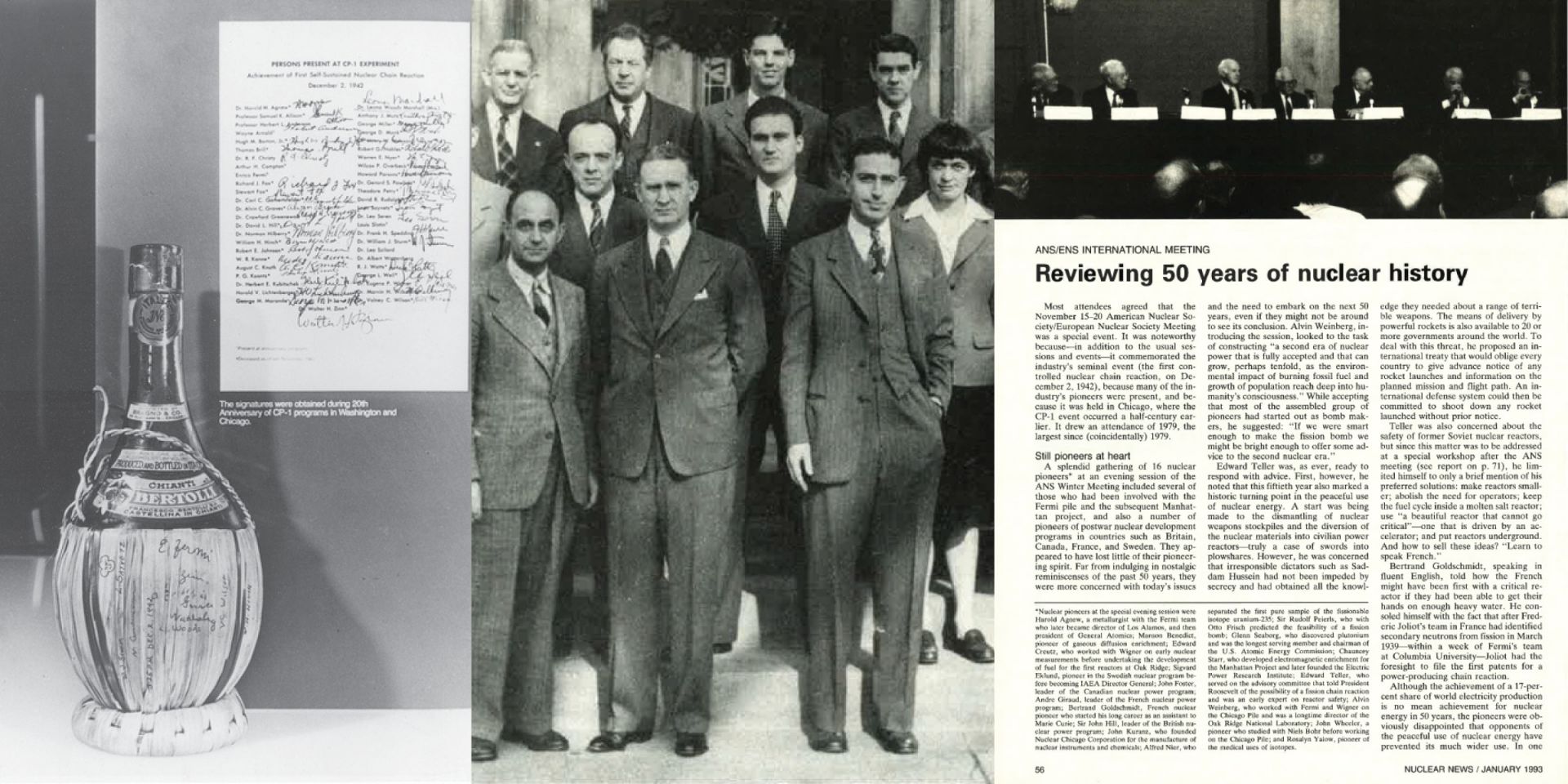

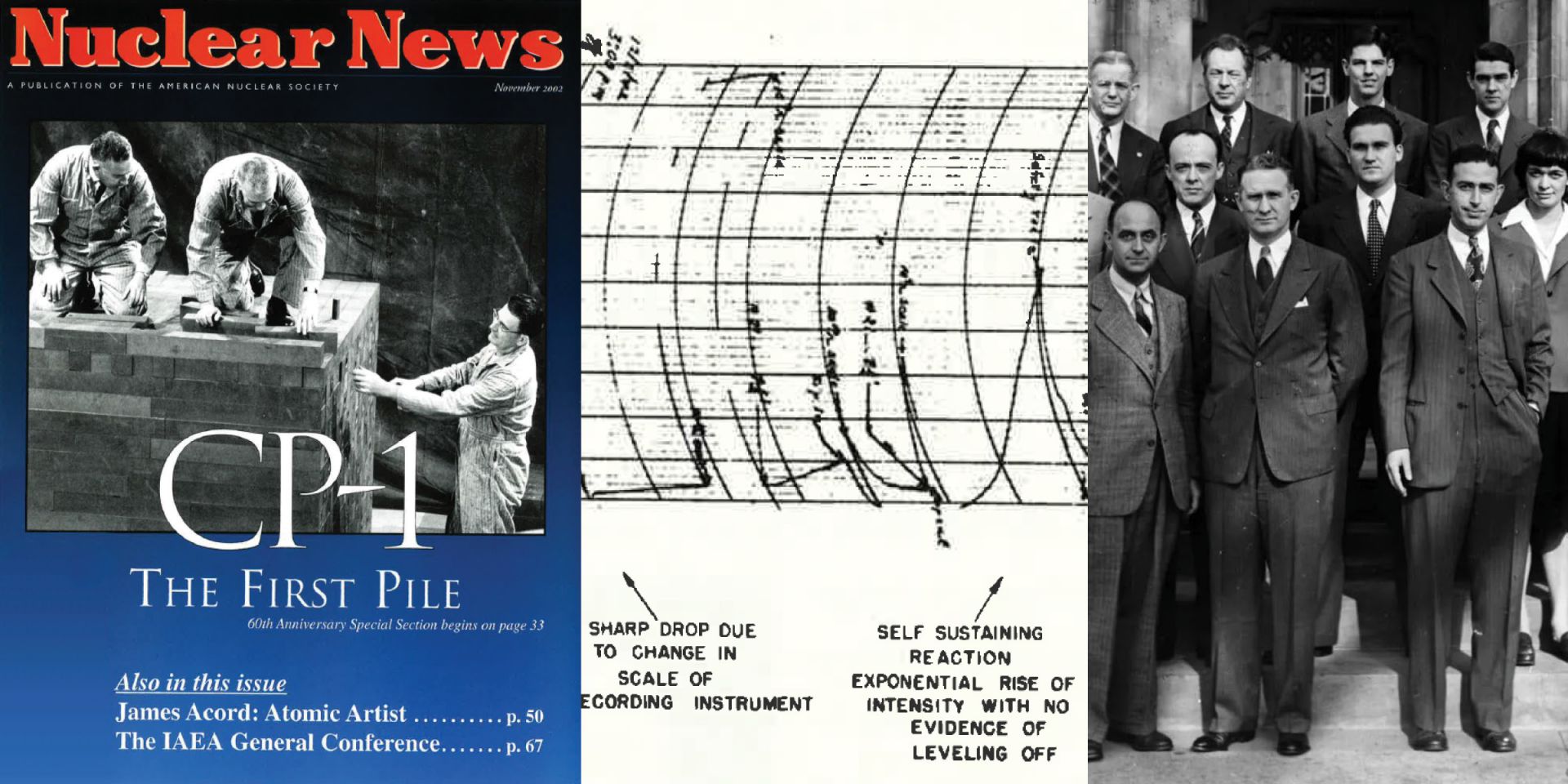

At a moment of global crisis, in a windowless squash court below the football stadium bleachers at the University of Chicago, a group of scientists changed the world forever.

On December 2, 1942, a team of researchers led by Enrico Fermi, an Italian refugee, successfully achieved the world’s first human-created, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Racing to beat Nazi Germany to the creation of an atomic weapon, the team of researchers, working as part of the Manhattan Project, split uranium atoms contained within a large graphite pile—Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor ever built.

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, Nuclear Newswire is back with the second of three prepared #ThrowbackThursday posts of CP-1 coverage from past issues of Nuclear News.

On November 17, we surveyed the events of 1942 leading up to the construction of Chicago Pile-1, an assemblage of graphite bricks and uranium “pseudospheres” used to achieve and control a self-sustaining fission reaction on December 2, 1942, inside a squash court at the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field.

Today we’ll pick up where we left off, as construction of CP-1 began on November 16, 1942.

Aecon-Wachs, the U.S. division of Aecon Nuclear, has been tapped to support the Department of Energy’s goal of repurposing the unfinished Mixed Oxide Fuel Fabrication Facility at the Savannah River Site (SRS) in South Carolina. Known as Building 226-F, the facility is being transitioned into the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility (SRPPF) to produce plutonium pits for the nation’s stockpile of nuclear weapons.