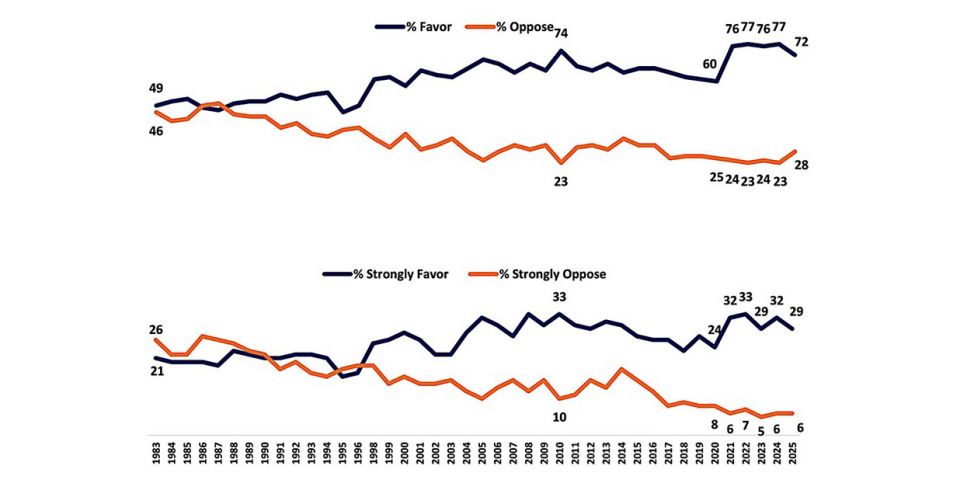

Why is there irrational fear of radiation?

Improvements are needed in explaining the significance of the numbers to the public

Editor for this multi-author blog post: Dan Yurman

The Fukushima reactor complex, before March 11, 2011, provided 10% of Japan's nuclear generated electricity.

The crisis at the Fukushima nuclear reactor complex in Japan, caused by a record earthquake and equally record shattering tsunami, has created a maelstrom of fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) when it comes to radiation measurements.

For instance, the importance of distinctions between fast and slow decaying isotopes of iodine and cesium are sometimes lost on media and the public.

Worse, the differences between accounting for the sheer amount of radiation and giving an assessment of the potential health effects of uncontrolled releases takes place using different sets of measurement units. Is it any wonder that mainstream news media editors get headaches when their reporters file stories about radiation?

It hasn't helped that Japanese and American nuclear experts have called for different distances for evacuation zones around the plant site. Can we fault the public for concluding that any report about radiation at a nuclear reactor is bad news?

Organizations with agendas that call for removing nuclear reactors from the energy mix have been known to exploit public fears of radiation. In doing so, they've sometimes failed to understand the scientific basis for the measurements.

In one case, a critic of a reactor relicensing application, writing in a political news magazine, said that a tritium release was 500 times more than expected, which was none. What he failed to realize is that the measured quantity was still 500 times less than the EPA drinking water standard.

Calling this type of mistake "junk science" misses an important point. What the public thinks is that regardless of how much radiation you are talking about, it is colorless, odorless, and tasteless. FUD fosters fear.

On the other hand, people in the nuclear energy field, who routinely work with some of the most dangerous radioactive materials in the universe, are quite calm about it, citing and practicing the principles of time, distance, and shielding. In fact, some can't understand what all the panic is about because they know, by the numbers, that the risk isn't commensurate with the noise level.

Is it time for a change in the way radiation measurements are communicated and explained to the public? At the ANS Social Media list, I asked four contributors to share their views on this question.

These four people have deep insights into the world of nuclear energy, but they also have very different takes on the current systems of radiation measurement and how they are used to explain risk to the public and the press. In this multi-author guest blog post, an ecologist, a chemist, an energy expert, and a public affairs consultant offer ideas about what to do about making radiation numbers more understandable and, in doing so, foster better public understanding about what they mean.

Is obfuscation deliberate?

~ Stewart Brand

The aversion to nuclear would be due to aversion to the uncertainty of radiation risk, itself a product of lack of familiarity with the weird units of measurement.

NO KIDDING! Sieverts, rems, rads, grays, becquerels, curies, and roentgens are reported in their densely confusable forms of milli, micro, and mega. None of them are calibrated around dimensions that might make intuitive sense concerning human safety, and they all obfuscate each other.

Listening to engineers debate about how many microcuries can dance on the head of a megabecquerel all by itself introduces profound dread in anyone listening in.

With its Babel of measurements, the nuclear power industry has guaranteed that all of its communications with the public are maddeningly confusing and frightening.

It is such conspicuously incompetent social engineering that observers understandably suspect that the nuclear engineering behind it is equally incompetent, and that nuclear engineers must hate people.

Stewart Brand, an ecologist, is the author of many books including, most recently, "The Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto" (Amazon) or see his home page.

Stick with health effects measurements

~ Cheryl Rofer

What people want to know about radiation is whether it's a danger to them. What they get is numbers with funny units attached. These numbers may be presented as multiples of some standard. But that doesn't say what the health risks are. Recent changes in the units themselves have provided more confusion, along with the prefixes indicating powers of ten.

Each unit has a use:

- Monitoring instruments count disintegrations (counts per second, becquerel, curie); roentgens,

- Rads and grays measure the absorbed energy from those disintegrations; and

- Rems and sieverts measure the biological dose.

All of which moves toward health effects. But there is a big step missing.

That step is how the biological dose translates into disease, cancer in particular. That translation depends on many factors: the age and sex of the person exposed, the rapidity of the exposure, which part of the body is irradiated, and very likely the basic health of the person exposed and his or her genetic makeup. Even when all that is combined for an individual person, the result is a probability, not a certainty.

I don't see an easy way to make these units more understandable. But it would help if regulators, engineers, and reporters would stick with sieverts or millisieverts. These are the units and the range most relevant to health effects.

Cheryl Rofer, a chemist, worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 37 years on a variety of projects, many of them related to the nuclear fuel cycle. Her blog is The Phronesisaical, covering politics, philosophy, and fruit

No one has died from radiation at Fukushima

~ Steve Aplin

Why do we fear radiation? Throughout the Fukushima emergency, media stories have reported radiation in terms of picocuries, becquerels, rads, grays, millirems, microsieverts. Few of us know what these units represent; they sound ominous, uncontrollable. They scares us. In the 21st century, with our digital TVs and smart phones, we humans are still afraid of the dark.

There is one measurement, however, that almost nobody has mentioned in the coverage of Fukushima. It is a familiar number-zero. It represents the number of people who have died, so far, from radiation at the plant. That's right: after five weeks, thousands of hours of broadcast airtime, and millions of newspaper column-inches, zero people have died.

The number zero may be familiar to us today, but it took thousands of years to enter our mathematical lexicon. That's because as a concept, it is extremely elusive and complex.

Zero's subtlety may be why "zero deaths by radiation" has so little effect on our gut-level imagination. Contrast that with lurid descriptions of something unknown, out beyond the edge of darkness, beyond our control: something measured in picocuries, microsieverts. That "something" grabs our imagination; its mystery scares us. "Zero deaths" does neither.

Well, when you step down into a dark basement, what's the quickest way to turn off your fear? Turn on the light. Same with curies, rads, and microsieverts. The light of knowledge will help. Learn about radiation.

When you do, you'll understand why there have been zero deaths because of radiation at Fukushima.

Steve Aplin is vice president of Energy and Environment at The HDP Group, an Ottawa-based management consultancy. He blogs at Canadian Energy Issues.

Say it simply and say it in English

~ Mimi Limbach

The events at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant have brought many technical experts into contact with journalists who have little knowledge of nuclear energy, science, and technology.

Some of these experts are speaking a different language-jargon-than the journalists and the public. Environmentalist Stewart Brand said it better than anyone in a companion blog to this one. I showed his comment to a group attending last week's ANS Student Conference, and it brought down the house with laughter. As my audience looked sheepishly at each other, it was clear that most people in the room were guilty of using jargon that would be incomprehensible to the public.

Risk communication research tells us that when people hear jargon, they believe the speaker is trying to mislead them. So when you use jargon, you're also losing credibility with your audience.

Several years ago, I attended a community meeting in Jackson, Wyo., about a controversial facility that was to be built nearby. In the midst of a presentation, the woman sitting next to me said, "What are they hiding from us? Why can't they just say it in simple English?" The facility was never built.

Jargon is a shortcut for technical professionals ... or a very precise way of expressing concepts or measures. It works for technical audiences. But to most people, it is meaningless and insulting.

So, how should technical people make complex ideas meaningful to the public? Use examples and analogies that relate radiation measures to something we all live with in our everyday lives. Say it simply. And say it in English.

Mimi Limbach is a partner at Potomac Communications Group, Washington, DC. Her business blog is From the Potomac.

Last word from blog post editor

All four contributors, coming at the problem from very different perspectives, nevertheless find fault with the way current radiation measurement systems explain their results. The fault finding is not with the internationally accepted scientific measurement units, but rather in communication of the numbers to a skeptical and fearful public.

Until risk communication practice by nuclear regulatory agencies catches up with the public's needs for understanding, the nuclear industry may paradoxically continue to find itself sliced and diced in the news media by its own measurement precision.

____________________________________________________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy. From 1994 to 1999 he served as a citizen member of a Federal Advisory Committee to the Centers for Disease Control on radiation health effects studies at Department of Energy sites.

-3 2x1.jpg)