First Light Fusion shifts focus from power to amplify its technology and revenue

First Light Fusion announced last week that it has set a new record for the highest quartz pressure achieved on Sandia National Laboratories’ Z machine using its amplifier technology to achieve an output pressure of 3.67 terapascal (TPa)—roughly doubling the pressure the company reached in its first experiment on the machine one year ago.

First Light Fusion, which is based near Oxford University in the United Kingdom, developed the technology to support its own fusion energy design. The Z machine experiments demonstrate the viability of that technology at other facilities and, “critically, when driven by different types of projectiles and drivers,” First Light said. That fits the company’s new strategy. In early March, First Light announced it would abandon its own plans to build a fusion energy machine, instead using its technology to help others “access pressure regimes that will support vital materials science research in fusion, defense, and space science.”

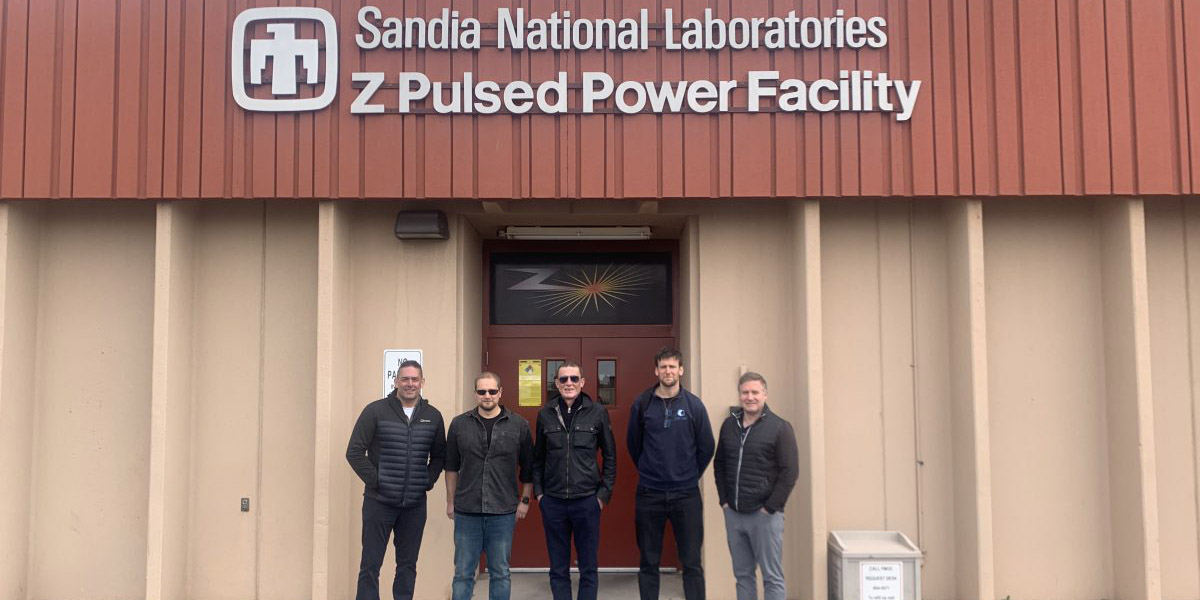

At the Z machine: With a peak power of 80 trillion watts, the pulsed power Z machine is the world’s most powerful laboratory radiation source. Impacting samples with electromagnetically launched particles allows researchers to test materials at extreme pressures. The company’s experiments at Sandia form part of the lab’s “Z Fundamental Science” experiment program. First Light reports it has more experiments planned at Sandia over the next 12 months.

According to First Light, its amplifier technology has helped the Z machine break a long-standing pressure record for the facility, reaching—with 3.67 TPa in February 2025—a pressure equivalent to 10 times the pressure at the center of the Earth.

The experiment was led by Jon Skidmore and Guy Burdiak, principal scientists at First Light, in collaboration with Sandia’s Pulsed Power Sciences Center Department.

“The concept of target-based power amplification successfully demonstrated on the Z machine can enable a simpler and more cost-effective route to commercial fusion across multiple drivers,” Skidmore said.

Becoming a supplier: Earlier this month, First Light announced a new operating strategy, abandoning its plans for a projectile fusion power plant to seek commercial partnerships with other companies that could use its amplifier technology. The company attributed the change as an opportunity to “capitalize on the huge IFE [inertial fusion energy] market opportunities enabling earlier revenues,” and attributes to opportunity to “advancements in First Light’s proprietary amplifier technology, combined with progress in the wider [IFE] sector.”

According to the company’s early March press release, “This shift will significantly reduce First Light’s funding requirements while accelerating the path to revenue generation.” In other words, First Light thinks it can make money faster by marketing its technology than it could by marketing energy.

That announcement followed a recent leadership shift. Mark Thomas, who has 30 years of experience in the aerospace and defense industries, including as chief engineer at Rolls-Royce, was announced to be the new CEO in February.

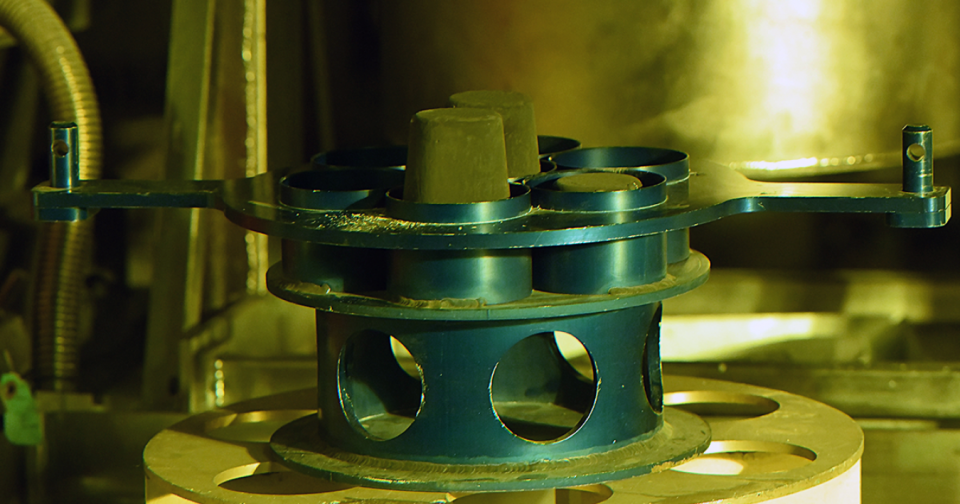

Specific plans: First Light will focus on targets “for all inertial driver schemes, including lasers,” by designing and manufacturing “consumable ‘targets’ embedded with its proprietary amplifier technology.” This technology “concentrates and shapes pressure to amplify power,” First Light said. The company estimates that fuel amplifiers represent about 20 percent of the inertial fusion value chain.

The company also plans to “partner with companies, universities and institutions in non-fusion sectors that can benefit from its unique technology and research facilities . . . across sectors including space exploration and defense.” First Light pointed to new research with NASA and the Open University on high velocity impact testing of spacebound materials that will involve First Light leasing its technology and providing expertise.

Not the only one: First Light Fusion is not the only company to look for a profit from the technological expertise it gained while in pursuit of fusion power. In this, it has something in common with Commonwealth Fusion Systems, a magnetic confinement fusion developer based in Devens, Mass., which has begun marketing its high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnet technology to other fusion developers. In February, CFS and Type One Energy (which is developing fusion stellarator technology) announced that they had signed an agreement giving Type One an exclusive license to use CFS’s HTS cable technology in its own proprietary stellarator magnets. Realta Fusion also used CFS’s HTS technology in a recent mirror fusion test.

There’s one critical distinction, however: CFS has not abandoned its own plans for power generation. The company announced in December that it planned to build a power plant in Virginia near a retiring coal plant and have it operating in the early 2030s.