Argonne’s NSTF: Active testing of passive cooling

A facility at Argonne National Laboratory has been simulating nuclear reactor cooling systems under a wide range of conditions since the 1980s. Its latest task, described by Argonne in an August 13 news release, is testing the performance of passive safety systems for new reactor designs.

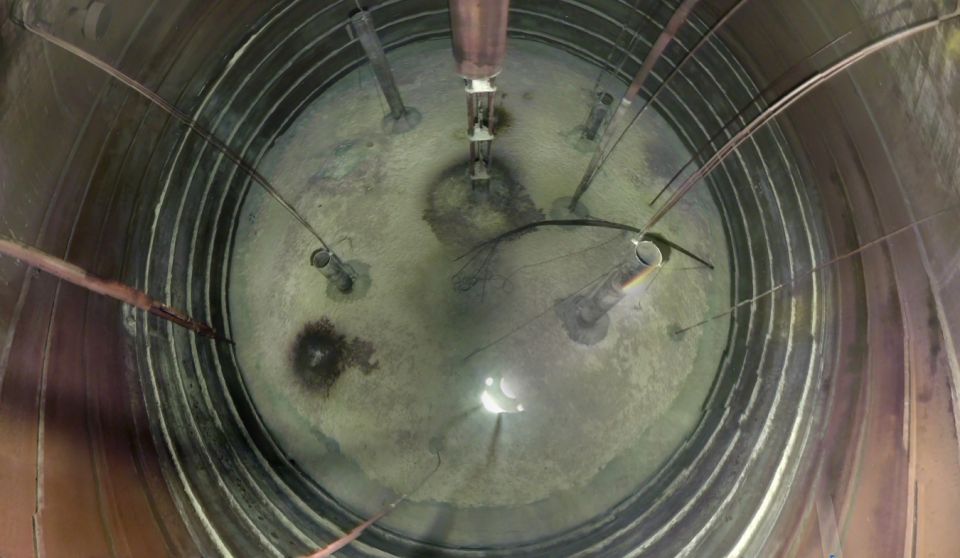

Designed as a half-scale model of a real reactor system, Argonne’s Natural Convection Shutdown Heat Removal Test Facility (NSTF) is used for large-scale experimental testing of the performance of passive safety systems, which are designed to remove decay heat using natural forces including gravity and heat convection. Those tests yield benchmarking data qualified to the level of National Quality Assurance-1 (NQA-1) that is shared with vendors and regulators to validate computational models and guide licensing of new reactors and components.

-3 2x1.jpg)