WHAM: Realta gets first plasma with 17 Tesla magnets in mirror fusion test

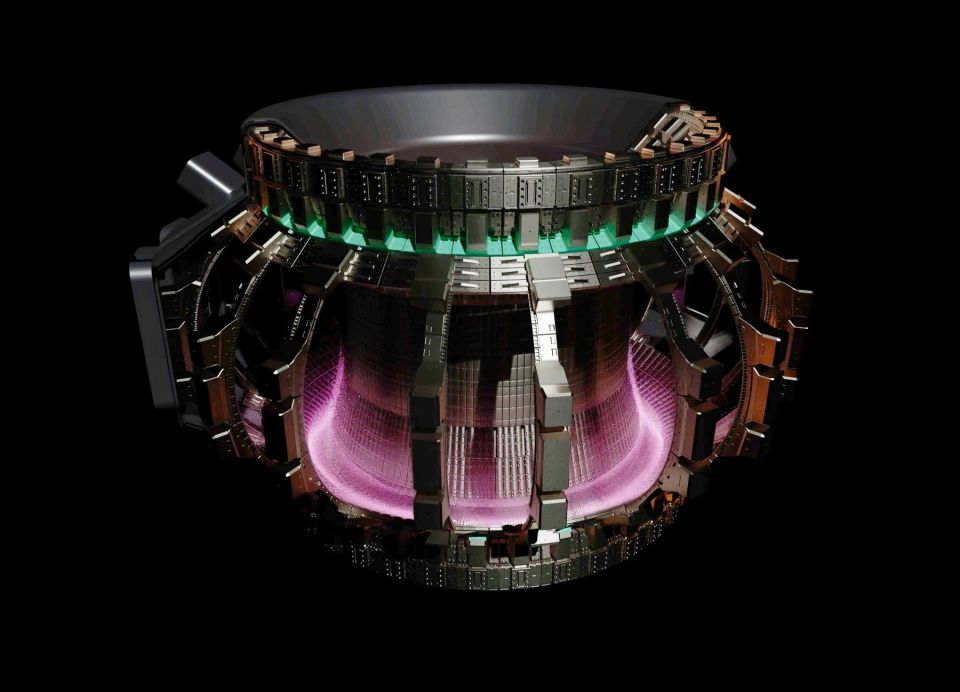

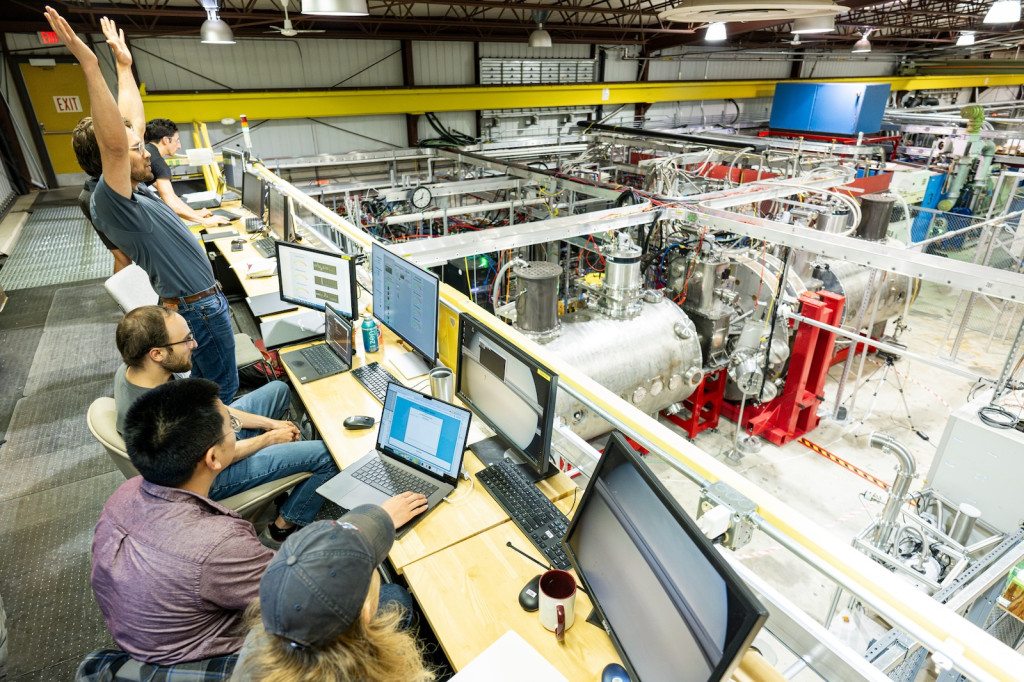

The magnetic mirror fusion concept dates to the early 1950s, but decades ago it was sidelined by technical difficulties and researchers turned to tokamak fusion in their quest for confinement. Now it’s getting another look—with significantly more powerful technology—through WHAM, the Wisconsin HTS Axisymmetric Mirror, an experiment in partnership between startup Realta Fusion and the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

-3 2x1.jpg)