Exelon to close Oyster Creek early

Deal with New Jersey will let it operate for 10 more years without having to build cooling towers

No one is happy with the decision by Exelon (NYSE:EXC) to close its 615-MW boiling water reactor at Oyster Creek in New Jersey. The company made the announcement on December 8 that it would shut down the plant in 2019, just halfway into its 20-year operating license issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in April 2009. The company said in a statement that a "unique set of economic conditions and changing environmental regulations" make ending operations in 2019 "the best option."

No one is happy with the decision by Exelon (NYSE:EXC) to close its 615-MW boiling water reactor at Oyster Creek in New Jersey. The company made the announcement on December 8 that it would shut down the plant in 2019, just halfway into its 20-year operating license issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in April 2009. The company said in a statement that a "unique set of economic conditions and changing environmental regulations" make ending operations in 2019 "the best option."

The economic challenges faced by the small reactor are 1) the lower demand for electricity brought on by the deep and seemingly intractable recession and 2) the costly maintenance. The environmental challenge is the one that has created the most controversy. At the state level, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie had decided to push the requirement that the reactor be told to build expensive cooling towers as a condition of its water pollution control permit.

At the federal level, the Environmental Protection Agency is considering a rule under Section 316 of the Clean Water Act to require power plants to reduce their thermal discharges into the nation's waterways. Draft regulations are expected in early 2011.

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie

Perhaps the most dramatic item in the news is that just prior to Exelon's announcement, Gov. Christie told a group of editors at a media roundtable that he thought the company was bluffing over the cooling towers issue. For more than a year, Exelon has been telling the state of New Jersey that it would be too expensive to build the cooling towers. The company said that if the state moved ahead with the requirement, it would close the plant. According to various estimates, the cooling towers could cost between $200 million-$800 million.

Reactions swift to reactor closing

In Washington, Rep. Fred Upton (R.,Mich.) issued a statement in which he called the news that Oyster Creek was closing early "a wake-up call that rampant regulations are shutting down power plants and costing jobs."

"Oyster Creek is a foreboding sign of what awaits the nuclear power industry if federal and state regulators continue to promulgate rules and regulations with no cost-benefit analysis. We cannot allow bureaucrats to regulate the nuclear energy sector out of business-nuclear is a reliable, inexpensive, and emissions-free source of power. It is the citizens of New Jersey who will pay the price, as Oyster Creek powers 600 000 homes and employs 700 folks," Upton said.

Upton, who will chair a House Committee that oversees the NRC, told the New York Times that the news the reactor will close is "the first domino" of what could be a slew of forced nuclear and coal plant closings. Upton's comment is a reference to the Cold War "domino theory" of nations that might fall to communist aggression.

Upton, who will chair a House Committee that oversees the NRC, told the New York Times that the news the reactor will close is "the first domino" of what could be a slew of forced nuclear and coal plant closings. Upton's comment is a reference to the Cold War "domino theory" of nations that might fall to communist aggression.

MorningStar, an investment advisory and financial news wire service, said that there might be more to the economics of the plant closing than just the cost of cooling towers. In a December 9 message to subscribers, the wire service called Oyster Creek the "lowest margin plant" for Exelon, and said that it had been plagued by "relatively high operating costs."

Chris Crane, Exelon chief executive officer, told the New York Times on December 8 that if maintenance expenses run up too quickly, the firm might close the reactor even earlier than 2019. Coincidentally, on December 10, one of the plant's two main transformers-a $16-million unit-failed and now requires a replacement. In addition, since 2009, Exelon has spent $13 million cleaning up leaks of radioactive tritium from underground pipes.

MorningStar also said that the closing of Oyster Creek could have an upside for other power generators in the region. Removing 6 percent-8 percent of the electricity generation capacity in the New York-Philadelphia region would boost the value of the remaining plants owned by Public Service Enterprise Group (NYSE:PEG), among others. The plants includes 2300 MW at the two-unit Salem nuclear plant and the 1160-MW Hope Creek plant, both located in southwest New Jersey on the banks of the Delaware River.

![]() Exelon's Eddystone Generating Station, just across the Delaware River from the reactors in New Jersey, generates power from two coal-fired power units and two more natural gas fuel-powered units. In 2009, Exelon announced that the coal units will be retired by 2012, leaving a combined total of 820 MW of fossil-fueled power that will be more valuable to the region once Oyster Creek shuts down in 2019.

Exelon's Eddystone Generating Station, just across the Delaware River from the reactors in New Jersey, generates power from two coal-fired power units and two more natural gas fuel-powered units. In 2009, Exelon announced that the coal units will be retired by 2012, leaving a combined total of 820 MW of fossil-fueled power that will be more valuable to the region once Oyster Creek shuts down in 2019.

The NJ Chapter of the Sierra Club, which has been trying to close the Oyster Creek reactor for years, was not pleased with the deal that Exelon struck to keep the plant open for another nine years without having to build the cooling towers.

Sierra Club chapter director Jeff Tittel told the Trenton Times on December 8, "Exelon gets to operate the plant for 10 years, then walk away with a pile of cash at the expense of the bay."

Bob Martin, a New Jersey environmental official, told the Wall Street Journal on December 10 that the agreement with Exelon gives the utility "predictability," and it saves the state from the delay and expense of protracted litigation. Negotiations took almost a year to complete to seal the deal for early closure as a price for not having to build the cooling towers.

Regardless of when the reactor closes, it will take Exelon at least two years to transition it from an active, operating reactor to a site made ready for decommissioning. It could be at least 10 years before the decontamination and decommissioning process gets underway, but when it does Exelon has $750 million in a decommissioning fund to pay for the work.

It could be even longer before the used nuclear fuel now stored at the reactor site goes anywhere, as the United States has no long-term plan for management of it from any reactor. A Department of Energy Blue Ribbon Commission, which includes Exelon CEO John Rowe as a member, is expected to make draft recommendations for national policy changes in 2011.

Thermal pollution and cost benefits

The EPA won't release draft regulations under Section 316(b) of the Clean Water Act until sometime in 2011. Final regulations could be several years away. One of the key areas of contention will be the possible use of cost-benefit analysis to assess the costs of new pollution control technologies for older power plants against the benefits of protecting fish and other aquatic wildlife. In April 2009 ,the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that EPA can conduct such an analysis as part of its efforts to regulate power plants that draw water from rivers and then discharge it back to them.

The EPA won't release draft regulations under Section 316(b) of the Clean Water Act until sometime in 2011. Final regulations could be several years away. One of the key areas of contention will be the possible use of cost-benefit analysis to assess the costs of new pollution control technologies for older power plants against the benefits of protecting fish and other aquatic wildlife. In April 2009 ,the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that EPA can conduct such an analysis as part of its efforts to regulate power plants that draw water from rivers and then discharge it back to them.

The lawsuit that was the basis for the Supreme Court's 6-3 ruling was brought by Riverkeeper, a New York environmental group that has been trying to impose cooling towers on the Indian Point Energy Center, located on the Hudson River in Westchester County, just north of New York City. Riverkeeper wanted to prevent the EPA from using cost-benefit analysis methods to evaluate permit conditions to control thermal pollution. As a result of the Supreme Court ruling, in July 2010 the EPA asked for public comment on the use of cost-benefit analysis in preparing the new Sec. 316 regulations. The EPA still hasn't conducted the survey.

Indian Point's cooling tower controversy

Indian Point is owned and operated by Entergy (NYSE:ETR). The 2200 MW of power supplied by the twin reactors are a major source of electricity for the New York metro area. It includes all the electricity used to power the city's subways that carry 5.1 million riders a week.

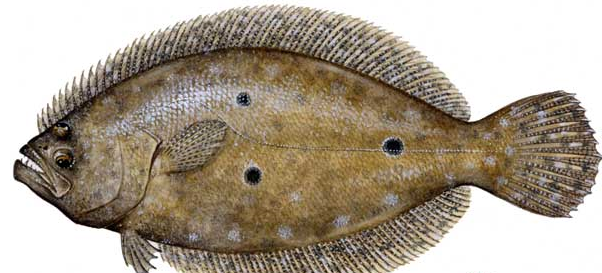

On April 2, 2010, the state of New York denied a water quality permit under the Clean Water Act to Indian Point. The state said that the permit was denied because the plant harms certain fish-shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon, which are endangered species-when they are pulled against intake screens for the cooling system that uses 2.5 billion gallons of water a day. The water is returned to the Hudson 20 degrees to 30 degrees warmer. In its letter, the New York state Department of Environmental Conservation wrote that because Indian Point is causing "fish mortality," the plant is "not in compliance."

On April 2, 2010, the state of New York denied a water quality permit under the Clean Water Act to Indian Point. The state said that the permit was denied because the plant harms certain fish-shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon, which are endangered species-when they are pulled against intake screens for the cooling system that uses 2.5 billion gallons of water a day. The water is returned to the Hudson 20 degrees to 30 degrees warmer. In its letter, the New York state Department of Environmental Conservation wrote that because Indian Point is causing "fish mortality," the plant is "not in compliance."

The denial of the permit is a potential roadblock to relicensing the two reactors at the Indian Point plant. The NRC requires all state environmental permits to be in place, and the plant in compliance, before it will extend the licenses for the two reactors for another 20 years. The plant licenses expire in 2013 and 2015.

Cost of cooling towers

The state of New York has called for Entergy to build cooling towers and has rejected its plan for better screens on intake pipes. For its part, the utility has said that the cooling towers are too expensive and that it will close the reactors rather than build them. The permit issue is now before an administrative law judge.

Entergy said in a statement that new cooling towers, which would support a closed-loop system, would cost $1 billion and take the plant out of operation for as long as 42 weeks. Permit approvals could take years before the first shovel of dirt was moved to build them.

This is exactly the type of fulcrum for political leverage that environmental groups such as Riverkeeper have sought for years. The group's objective, which now appears to be reaching its intended conclusion, is to impose regulatory burdens on the plant that make it too expensive to operate, forcing Entergy to shut down the plant rather than pass along the costs to stockholders.

Is this really about fish?

New York Governor Elect Andrew Cuomo

New York Governor-elect Andrew Cuomo won his office in November 2010 with the support of environmental groups because of his stand against relicensing of Indian Point. Cuomo has made a point of courting Riverkeeper and other environmental groups with his aggressive campaign against the reactor.

Cuomo has not answered questions about where replacement power would come from if the reactors would be closed or the trade-offs between saving fish and the additional greenhouse gases that would be released from replacement fossil-fueled power plants.

Alex Matthiessen, president of Riverkeeper, said that the power generated from Indian Point "is replaceable," but he did not say from what sources. In a more telling comment to the New York Times, he said, "For all we know, this is it-the beginning of the end (of Indian Point)."

Entergy may yet prevail, either as a result of an administrative ruling, or in court, citing evidence that improved fish screens are far more cost effective than a $1-billion set of cooling towers. The Clean Water Act was never intended to be a bludgeon to be used in defense of sturgeon. Stay tuned.

___________________________

Dan Yurman publishes Idaho Samizdat, a blog about nuclear energy. He is a contributing reporter at Fuel Cycle Week and a frequent contributor to ANS Nuclear Cafe.

-3 2x1.jpg)