Nuclear Technology: The Rewards and Penalties of Being Special

Years ago, a newspaper columnist intrigued me with a statement that science cannot tell us anything about real people. To the columnist, science could talk only about "average people," which exist only in the imagination of the speaker. The scientifically average American, for example, has one testicle and one breast, 2.3 kids, and 0.6 dogs. Most of us don't know anyone like that.

Growing up in such a world, it's comforting to be assured by parents and ![]() teachers that "you are special." Such assurance of specialness was granted the nuclear community. It brought respect, bright people, and high salaries, which in turn were used to create power plants of unprecedented safety, reliability, and performance.

teachers that "you are special." Such assurance of specialness was granted the nuclear community. It brought respect, bright people, and high salaries, which in turn were used to create power plants of unprecedented safety, reliability, and performance.

In a commercial society, however, specialness can be made into a penalty. When you start to solve a problem in the usual way-by adapting solutions that work in similar, non-nuclear situations-you're told, "Nuclear is special. Ordinary solutions are not good enough for nuclear applications." That may benefit the contractor who supplies or installs the extra frills that your specialness is said to require. But if the frills don't make the plant safer, or cheaper, or better in some way, then they merely add to the cost, and saddle you with a device or procedure that may bring problems of its own. Why should nuclear facilities be denied the problem-solving experience that everyone else depends on, and have to make do with impromptu suggestions and inventions?

So, what are the rewards and the benefits of being special? Here they are:

- It's a classic stimulus program. The more special, the more money comes in. The nuclear community became very good at this.

- The money, credibility, and other resources enabled the nuclear community to develop improved organizational structures, tests, and procedures that led to power plants with unprecedented reliability and safety. Not one member of the public has been killed by a commercial nuclear power plant of the kind that have been operated in America for more than half a century-a full lifetime in many parts of the world, two human generations.

- The advantages of the disciplined approach are more than safety, although that alone is enough to recommend it. But the performance records being set by nuclear plants, year after year, are also unprecedented. Prior to the TMI reforms, a 60 percent to 80 percent capacity factor (i.e., a 1000-MW plant would generate 600 to 800 megawatt-years during the year) was an excellent achievement. America's commercial nuclear plants now repeatedly exceed 90 percent.

- We proceed as if the lesson is that nuclear technology is so special that it requires a lot more restrictions and safeguards than other technologies. But that's not what the real world shows us. Ordinary technologies, like drilling for oil, or operating gas-fired or oil-fired plants, are killing people by the thousands, and polluting the earth, year after year. And for a century, the lessons from those incidents are being repeatedly ignored.

- The advisory committee set up to look for lessons from the recent Gulf of Mexico oil spill is recommending that the petroleum industry could benefit by reforming itself to operate more like the nuclear power industry. The benefits of being special are available to everyone. There is no basis for arguing that the nuclear business is especially hazardous, requiring additional specialness penalties. The evidence is all to the contrary.

- Saying that a lethal dose of radioactivity is worse than a lethal dose of mercury, arsenic, or botox, or that "man-made radioactivity" is 100 times more dangerous than "natural radioactivity," makes a mockery of science. We should stop doing that. Rewarding endless reduction of trivial radiation doses can reduce safety for no health benefit. (The easiest way to reduce total radiation dose is to minimize the time that workers spend in radiation zones. But that is where the most critical equipment is located, needing inspection, testing, and preventive maintenance.)

- None of this should be interpreted as a call to reduce safety standards. Real safety measures pay their own way. Adding more and more "safety requirements," however, does not necessarily make a system safer. There is wisdom in the advice, "Don't fix what ain't broke."

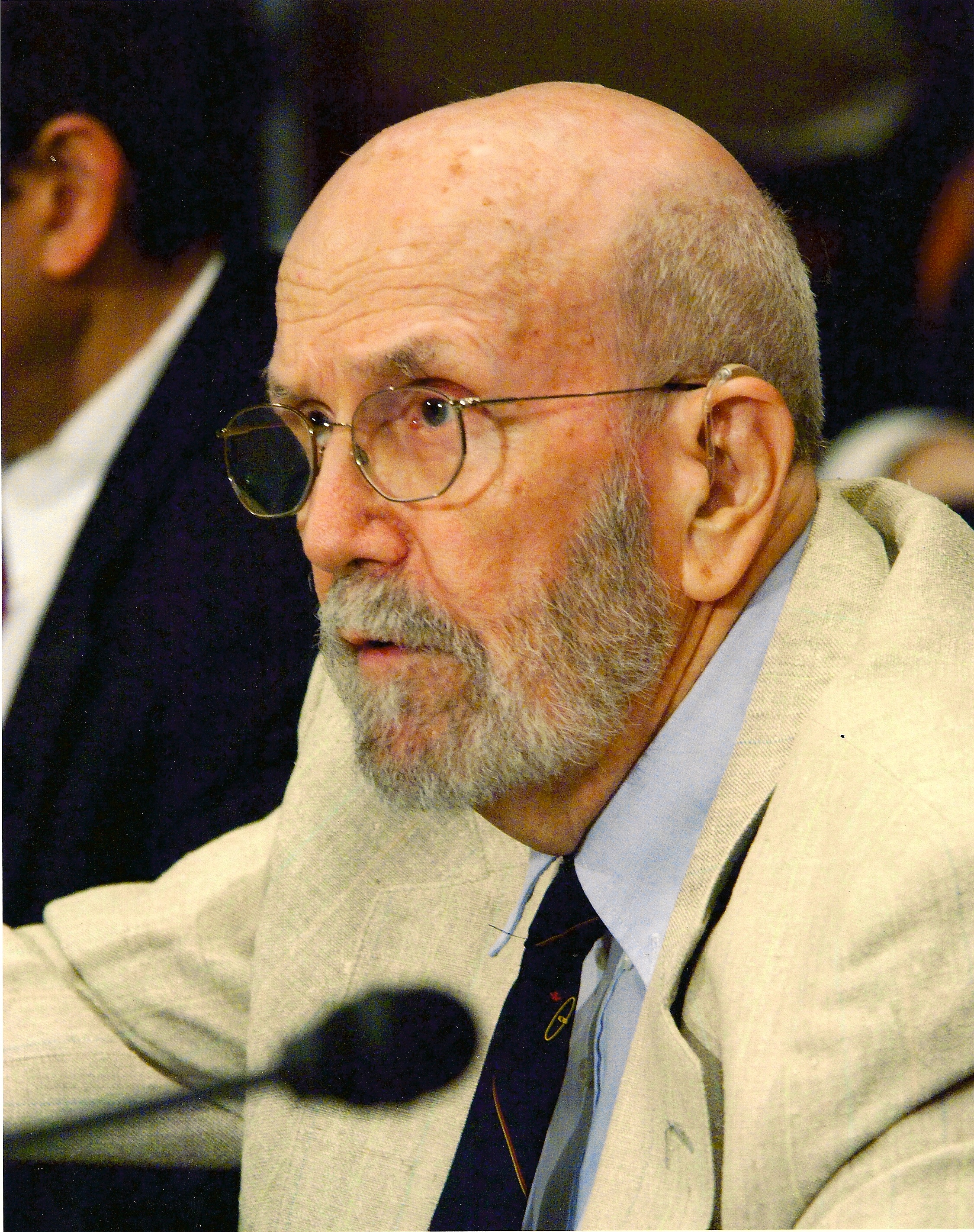

Ted Rockwell

Ted Rockwell wrote his first published article on nuclear technology, "Frontier Life Among the Atom Splitters," for the December 1, 1945, Saturday Evening Post. He was Adm. Rickover's technical director during the first 15 years of the naval propulsion program, while Rickover served as director of President Eisenhower's Atoms for Peace program. Rockwell then co-founded the international engineering firm, MPR Associates, and the public interest organization, Radiation, Science and Health. He was the first recipient of ANS's Lifetime Achievement Award, subsequently called The Rockwell Award. He is a member of the National Academy of Engineering and the author of several books, papers, and patents, including "The Reactor Shielding Design Manual" in 1956, which is still used as a standard textbook.

Rockwell is a guest contributor to the ANS Nuclear Cafe.

-3 2x1.jpg)