The NRC: Observations on commissioner appointments

In 2015, we wrote an article for Nuclear News analyzing the history of commissioners appointed to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and assessing their backgrounds, experience, and qualifications at the time of their appointment. At the time, ANS had not established a formal position statement on NRC commissioner appointees. Our article provided an objective assessment of historical patterns and was used to develop ANS position statement #77, The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (2016). This article draws upon the 2015 article and provides updated data and analysis. Also, the recommendations of the position statement are applied to the current vacancy on the commission.

The NRC is an independent federal agency with approximately 3,000 employees nationwide. It is responsible for regulating commercial nuclear power plants and other civilian applications of nuclear materials in the United States. The NRC is governed by a five-member panel of commissioners who are nominated by the president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate to serve five-year terms. The president appoints one of the commissioners to be the chairman and official spokesperson for the commission. No more than three commissioners can be appointed by one political party. On June 30 of each year, the term of one of the commissioners expires.

The commission formulates policies and regulations governing nuclear reactor and materials safety, issues orders to licensees, and adjudicates legal matters brought before it. The commissioners, and in particular the chairman, establish the vision and direction for the NRC and make or oversee all of the key decisions, including licensing actions and the selection of certain senior personnel (e.g., the NRC’s executive director for operations, who manages the NRC’s day-to-day operations). Moreover, the commissioners represent the agency to elected officials and the public. As a result, the NRC is hugely consequential to the present and future health of nuclear power in the United States. If the NRC regulates too stringently, innovation will be stifled and costs will rise, potentially to the point that nuclear power becomes uneconomical as a domestic source of electricity. If it regulates too loosely or ineffectively, public confidence in nuclear power will erode, and public health and safety may be put at undue risk. Accordingly, having a competent and qualified commission is extremely important, not only to the commercial nuclear power industry, but also to the larger nuclear community, including the Department of Energy, the national laboratories, and the universities. Absent competent, qualified commissioners, the NRC will not fulfill its mission in the long run, and all who practice in the field of nuclear technology will suffer.

Historically, the NRC has been a well-respected institution. It has been referred to as the “gold standard” for nuclear safety regulation worldwide. As an independent federal agency with an oversight role, the NRC has been viewed as largely nonpolitical in carrying out its mission of protecting public health and safety. That view has changed somewhat in recent years, however, primarily due to the controversy over actions related to the proposed geologic repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada, but also due to concerns expressed by antinuclear groups about a perceived lack of timeliness and stringency in the NRC’s regulatory actions.

The NRC was established as an independent agency by federal legislation in 1974, and the first commission was seated on January 19, 1975. As of January 1, 2020, 38 people have served or are serving as commissioners, and 18 of the 38 have served as chairman. Most commissioners have garnered little notice outside of the nuclear field. Over the past decade, however, several factors have focused increased attention on the NRC’s governing body. Those factors include the controversy leading to the resignation of former chairman Gregory Jaczko, unusually high turnover among other commissioners, persistent criticism of the NRC by several members of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, and acute political overtones in the commissioner nomination and confirmation process.

The NRC maintains on its website the official biographies of all commissioners, past and present. Those biographies were reviewed to establish the background and qualifications of all 38 people who have served as a commissioner, as of his or her time of service. Those data are aggregated in this article to catalog the background and qualifications of commissioners on a collective basis. Trends related to the selection of commissioners are identified, and insights are provided that may be pertinent to future commissioner nominations and chairman appointments.

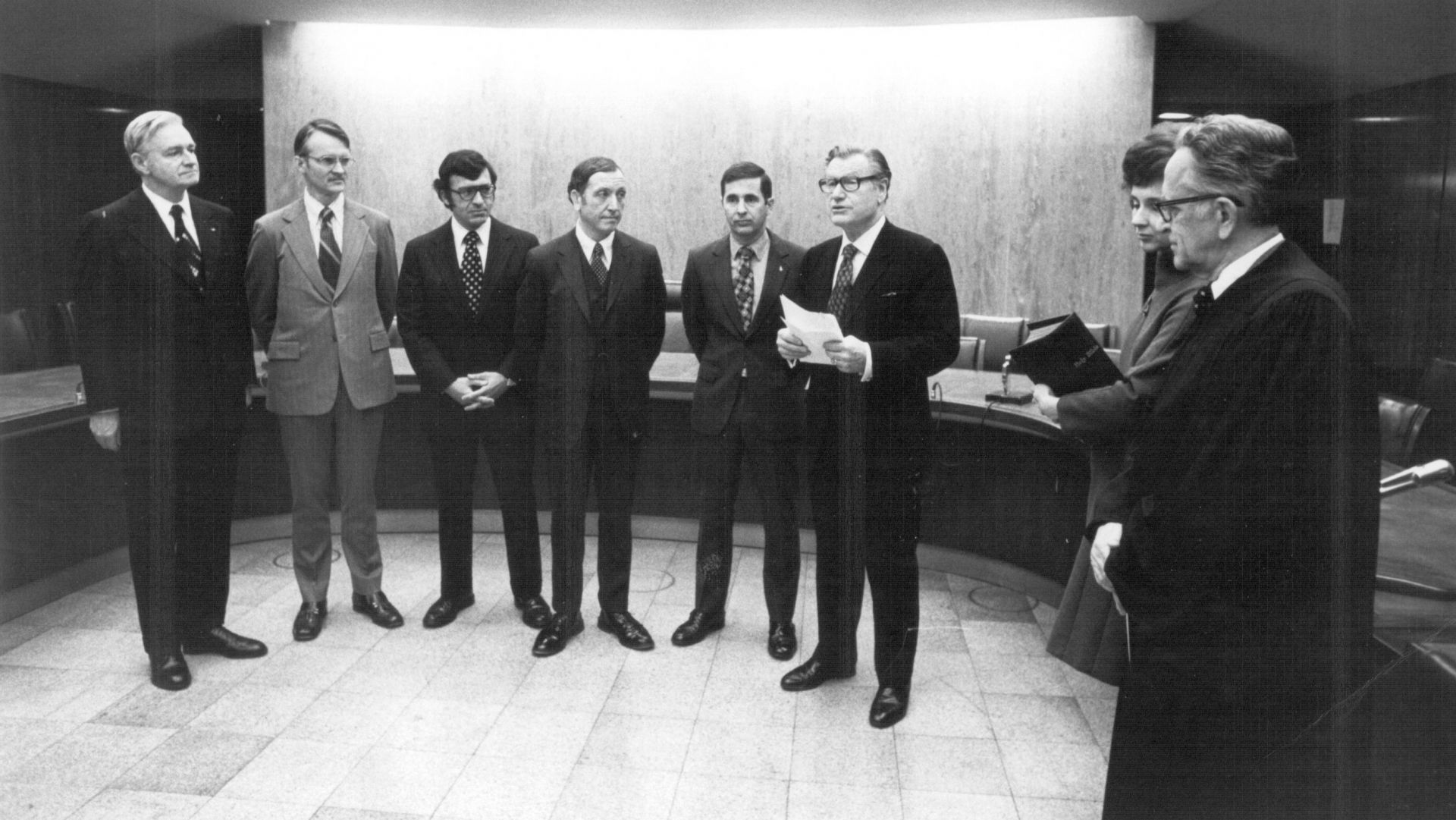

The NRC commissioners at the first swearing-in ceremony at the U.S. Capitol, January 23, 1975. Left to right: Richard T. Kennedy, Edward A. Mason, Victor Gilinsky, Marcus A. Rowden, William Anders (chairman), Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller, Mrs. Valerie Anders, and Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun.

The commissioners

The 37 people who have served or are serving as commissioners are a distinguished group with a variety of backgrounds, qualifications, and experiences. The five members of the first commission were William Anders (chairman), Marcus Rowden, Edward Mason, Victor Gilinsky, and Richard Kennedy. Three of the five (Anders, Mason, and Gilinsky) had technical backgrounds. Rowden was a lawyer and former head of the NRC’s predecessor agency’s Office of General Counsel, and he went on to chair the commission for a year following Anders’s resignation. Kennedy had a career in the U.S. Army, largely in policy and strategy roles, and served on the National Security Council staff prior to his selection as a commissioner. Republican president Gerald Ford nominated the members of the first commission, which consisted of two Republicans, one Democrat, and two independents.

Svinicki

Baran

Caputo

Wright

Hanson

The current commission consists of two Republicans, Annie Caputo and David Wright; and two Democrats, Jeff Baran and Christopher Hanson. Republican Kristine Svinicki, who had served as chairman since January 2017, departed the NRC on January 20, 2021, the third commissioner in a row to leave before the end of their term.

It is expected that President Biden will move quickly to name one of the Democrats to serve as chairman, at least for the time being. The president could also nominate another person to fill the vacancy left by Svinicki and, upon confirmation, could name the new commissioner as the chairman.

Two of the first five commissioners (William Anders and Edward Mason) resigned before the end of their terms, but between Mason’s resignation in 1977 and Dale Klein’s resignation in 2010, only three commissioners resigned prior to completing their terms: Peter Bradford, Ivan Selin, and Richard Meserve. During that period, it was common for commissioners to serve a full term, and eight commissioners served longer. Beginning with Klein’s resignation in 2010, however, eight commissioners have served and departed the NRC, and six of the eight (Klein, Jaczko, William Magwood, Allison Macfarlane, Stephen Burns, and Svinicki) resigned before the end of the terms they were serving. The recent increase in resignations has led to greater turnover and less experience on the commission.

Backgrounds of the commissioners

The NRC’s official biographies were used to determine certain characteristics of individual commissioners prior to their service on the commission. It is important to note that no specific qualifications are required for an individual to serve as a commissioner. With that being said, 13 characteristics and types of experience that are considered pertinent to the job are listed in Table 1, along with the percentages of the 38 past and sitting commissioners who possessed that particular attribute prior to beginning service on the commission. Both the mean and median number of the attributes possessed by individual commissioners was three. No commissioner was characterized by more than seven of the characteristics; all had at least one.

Table 1. Commissioner Characteristics

| % | Characteristic |

| 74% | Education in a technical field |

| 45% | Political experience on congressional staff, White House staff, or as a political appointee in an agency involved in nuclear matters |

| 32% | Experience as a college professor or instructor |

| 21% | Worked for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission or its predecessor agency |

| 18% | Law degree |

| 18% | Service in the Department of Energy or a predecessor agency |

| 18% | Worked for a state regulatory body overseeing nuclear matters |

| 18% | Experience in a nongovernmental organization or trade association |

| 16% | Experience in the nuclear industry |

| 13% | Member, Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards |

| 13% | National laboratory experience |

| 11% | U.S. Navy nuclear propulsion experience |

| 8% | Member, National Academy of Sciences or Engineering |

There is no objective measure of performance of individuals as commissioners, so there is no correlation between any of these attributes (or the number of these attributes) of individual commissioners and the performance of a commissioner in office. Nevertheless, to the extent that experience and achievements may be pertinent to the ability to carry out the job of commissioner, it is instructive to see the extent to which certain characteristics have been shared among past and present commissioners.

The percentage of commissioners with a formal education in science, engineering, or health physics is 74 percent. That percentage has always been high and has actually increased since the 1970s and early 1980s. However, on the current commission, only one of the four has a technical education; Caputo holds a bachelor’s degree in nuclear engineering from the University of Wisconsin.

A substantial number (45 percent) of commissioners served in the White House, on a congressional staff, or as a political appointee in an executive agency prior to becoming a commissioner. Interestingly, that number was generally much lower—in the 20 percent range—until the late 1990s, when it increased fairly dramatically. Beginning with Commissioner McGaffigan in 1996, 12 out of 16, or 75 percent of individuals acceding to the office of commissioner, have had a political background; three of the current commissioners have served either on a congressional staff or in an executive agency.

Of the 37 commissioners who have served, 17 are identified as Republicans, 14 as Democrats, and seven as independents. Six of the seven independent commissioners began service on the commission in 1986 or earlier. With the exception of Burns, all current and recent commissioners are linked to one of the two major political parties.

The percentage of commissioners with a background in academia has been fairly steady, in the 30 percent range. However, none of the four current commissioners has been a university professor or lecturer.

It used to be much more common for commissioners to have experience with the NRC or a predecessor agency prior to joining the commission, but only one former NRC employee (Burns) has been confirmed to the commission since Forrest Remick in 1989.

Although it was relatively rare for lawyers to serve on the commission, after William Ostendorff was confirmed in 2010, there were two more lawyers appointed (Burns and Baran) as commissioners. The three most recent appointees do not have a law background, and one sitting commissioner, Baran, is a lawyer.

The NRC has been routinely criticized by antinuclear groups for being too close to the industry it regulates, but that concern is not reflected in the characteristics of the commissioners. Since the early days of the commission, less than 20 percent of commissioners have had any commercial nuclear power experience. Only one sitting commissioner, Caputo, has experience working in the nuclear power industry.

Through the 1980s, it was not uncommon for commissioners to have served on the Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards (ACRS), the technical advisory body to the commission established by the Atomic Energy Act. The only former ACRS member acceding to the commission since 1989, however, was George Apostolakis, who completed his only term as commissioner in 2014. Apostolakis was also one of just three commissioners recognized for technical accomplishments by being named a member of the National Academy of Sciences or the National Academy of Engineering.

The 1980s and early 1990s saw the service of three commissioners associated with the U.S. Navy’s nuclear propulsion program, either as a civilian (Nunzio Palladino) or as a naval officer (retired admirals Lando Zech and Kenneth Carr). All three served as chairman during some or all of their tenure on the commission. Since Carr’s departure in 1991, Ostendorff is the only commissioner to have served as a naval officer.

The then NRC commissioners listen to staff discuss the agency’s international program activities during a public meeting on July 10, 2013.

Commission chairmen

President Gerald Ford selected a Republican, William Anders, as the first NRC chairman. It is often assumed that the chairman must be from the same party as the president, but that has often not been the case. The chairman was not from the party of the president during substantial portions of the presidencies of Republicans Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush, as well as Democrats Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton. Four of the first seven chairmen were independents, but the only independent chairman since 1991 is Burns.

Soviet Atomic Energy chairman Alexander Protsenko and NRC chairman Lando Zech at the signing ceremony for a bilateral agreement.

It has usually been the case that a new president will allow an NRC chairman to continue to serve in that capacity, even if he or she is not of the party of the president. In 1977, President Carter followed Gerald Ford into the presidency but allowed independent Marcus Rowden to serve out his term as chairman. In 1989, independent Lando Zech completed his term as chairman into the presidency of George H. W. Bush, who succeeded Ronald Reagan. Republican Ivan Selin served as chairman from 1991 to 1995, despite the presidential transition from George H. W. Bush to Bill Clinton in 1993. Similarly, Democrat Richard Meserve served as chairman from 1999 through 2003, well past the 2001 presidential transition from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush.

There have been three cases of a premature change in NRC chairmanship when a president of a different party was elected. (In this case, a premature change refers to a situation in which the president appoints a new chairman, but the sitting chairman continues to serve on the commission—that is, the individual has not resigned, and his or her term has not expired.) The first occurred early in the term of Ronald Reagan, who appointed Republican Joseph Hendrie as chairman in March 1981, replacing independent John Ahearne. The move was seen as a reaction to the slow pace of reactor licensing under Ahearne following the Three Mile Island-2 accident in March 1979. Interestingly, Hendrie had served as chairman from 1977 until President Carter replaced him with Ahearne in December 1979, in the aftermath of TMI.

President Carter meeting NRC Chair Hendrie in the Oval Office.

The second instance of a premature chairman transition following an election occurred when President Barack Obama replaced Republican Dale Klein with Democrat Gregory Jaczko in May 2009. The promotion of Jaczko, former aide to the then Senate majority leader Harry Reid and a staunch opponent of the proposed repository for spent fuel at Yucca Mountain, was seen by many as part of the Obama administration’s initiative to end the Yucca Mountain project. The third instance was when President Trump replaced Burns with Svinicki after his inauguration in 2017. Svinicki’s departure in January is somewhat different, since she left the commission voluntarily, although it is generally expected that a new chairman will be appointed early in President Biden’s term. This will be the third administration in a row to appoint a new chairman at the beginning of its term.

Backgrounds of the chairmen

Table 2. Chairman Characteristics

| % | Characteristic | Delta |

| 89% | Education in a technical field | +15.20% |

| 39% | Experience as a college professor or instructor | +7.31% |

| 28% | Political experience on congressional staff, White House staff, or as a political appointee in an agency involved in nuclear matters | −16.96% |

| 22% | Worked for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission or its predecessor agency | +1.17% |

| 17% | Law degree | −1.75% |

| 17% | Service in the Department of Energy or a predecessor agency | −1.75% |

| 17% | U.S. Navy nuclear propulsion experience | +6.14% |

| 11% | Worked for a state regulatory body overseeing nuclear matters | −7.31% |

| 11% | Member, Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards | −2.05% |

| 11% | National laboratory experience | −2.05% |

| 11% | Experience in the nuclear industry | −4.68% |

| 6% | Experience in a nongovernmental organization or trade association | −12.87% |

| 6% | Member, National Academy of Sciences or Engineering | −2.34% |

When Svinicki, the longest-serving commissioner, with over 12 years of service, was named chairman of the NRC in 2017, she was one of the more experienced commissioners at the time of her appointment. While it might seem desirable to select a chairman with prior commission experience, that approach is actually as much the exception as the rule. Hendrie became chairman immediately upon his appointment in 1977, as did Palladino in 1981, Selin in 1991, Meserve in 1999, Klein in 2006, and Macfarlane in 2013. In addition, Shirley Jackson became chairman shortly after joining the commission in 1995, and Burns was named chairman only two months after being appointed to the commission.

There have been 17 chairmen since the commission was constituted in 1975. Soon it will be 18, with a new chairman to be appointed by President Biden. Greta Dicus served as chairman for only four months; all others served for at least a year. Palladino was the longest-serving chairman, with a tenure of five years. Not including Svinicki, who served as chairman for four years, the average tenure as chairman is 2.6 years, and the median is 2.9 years.

We developed a compilation of characteristics of chairmen based on the official NRC biographies, in Table 2. In this instance, the percentage exhibiting a particular characteristic is based on all chairmen, not all commissioners. The far right column shows the difference between the value for all chairmen and the value for all commissioners (as provided in Table 1). A positive number means that the population of chairmen possessed this trait to a greater extent than the population of all commissioners. The compilation includes all 16 past chairmen, irrespective of length of service.

Most of the characteristics were present in the population of chairmen to a similar extent to which they were present in the population of all commissioners. The following, however, represent a few differences.

An even higher percentage of chairmen (89 percent) had technical educations than the commissioner population at large. In fact, the only two chairmen without a technical education were the two lawyers and former general counsels, Rowden and Burns.

A much smaller percentage of chairmen had a political background prior to service on the commission—28 percent as opposed to 45 percent. As with the population of all commissioners, the percentage of chairmen with political experience had been increasing, but the two chairmen before Svinicki, Macfarlane and Burns, lacked a political employment background, bringing the numbers back down. Only one chairman (Selin) had nongovernmental organization/trade association experience, compared to four commissioners.

The U.S. Navy’s nuclear propulsion program experience is significantly higher for chairmen, at 17 percent, than for commissioners at large. This statistic is somewhat misleading, however, relative to recent trends. The last chairman with nuclear navy experience was Carr, whose term ended in 1991.

Brian Sheron, director of Nuclear Regulatory Research, discusses with NRC chairman Dale Klein (center) and commissioner Peter Lyons (right) a Davis-Besse nuclear reactor vessel head model that shows the football-sized hole from boric acid corrosion discovered in the carbon steel vessel head in 2002.

Observations and analysis

While it is instructive to examine the historical characteristics of the commissioners, it is important to note that a correlation has never been made between such characteristics and actual job performance. In fact, there is no objective ranking system for commissioner job performance, so any such correlation, if developed, would necessarily be subjective and therefore somewhat suspect. It appears logical that certain types of experience—such as a technical education or prior experience with the NRC—would be beneficial for commissioners, but there is no way to establish how important such experience might be.

Commissioner Gregory Jaczko, seated next to chairman Dale Klein, addresses NRC staff questions during the annual All-Hands Meeting in May 2008.

As another example, membership in the National Academy of Sciences or National Academy of Engineering is a high honor indicating significant accomplishment and stature, but it is not clear that technical achievement at that level enables better oversight and governance of the country’s independent nuclear regulatory agency.

Management experience may well be an important characteristic for commissioners to possess, but that characteristic is not included on the list. While day-to-day management of the NRC employees is not a direct responsibility of the commissioners, they select the NRC staff’s senior management team and set in place policies and directives that influence how well and how efficiently the NRC carries out its mission. The primary reason for not including management experience is the difficulty in assessing that characteristic in an objective manner for all 38 past and present commissioners.

The American Nuclear Society develops position statements that reflect the Society’s perspective on issues of public interest that involve various aspects of nuclear science and technology. Position statements are prepared by key members whose relevant experience or publications inform the documents, which are then reviewed by ANS committees and divisions and approved by the Board of Directors.

In 2016, ANS adopted position statement #77, The Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which lists four criteria that administrations should consider when nominating candidates for commissioner:

1. First and foremost among qualifications for a majority of commissioners is a strong background in the science and application of nuclear technology, particularly nuclear safety and electrical power generation. It is not essential that all commissioners be scientists or engineers, but the nature of the commission’s responsibilities makes a technical background a highly desirable trait.

2. All commissioner nominees should have significant, recognized accomplishments in the technical, management, legal, regulatory, or policy fields.

3. In selecting and confirming nominees to the commission, consideration should be given to the makeup of the commission as a whole. When functioning well, the commission acts as a collegial body of individuals with diverse and complementary abilities and backgrounds.

4. The president and Congress should strive to keep the commission at its full complement of five serving commissioners, rather than allowing extended vacancies, particularly involving two or more open seats.

Given that only one of the four sitting commissioners has a technical background, it would be highly desirable for the next commissioner nominee to have a strong background in the science and application of nuclear technology (see Recommendation 1). Three of the four sitting commissioners came to their posts from positions on congressional staffs. It would restore some balance to the commission if the next nominee does not have a predominately political background (see Recommendation 3).

Finally, ANS considers it important that the Biden administration and Congress act in a timely manner to restore the commission to its full complement of five commissioners (see Recommendation 4). The NRC plays a vital role in the safe application of nuclear technology for the betterment of the citizens of the United States, and ANS’s recommendations are intended to help ensure that the commission can carry out its mission effectively.

Similarly, there is an international component to the job of a commissioner, whose duties include interacting with nuclear safety regulators from around the world. Accordingly, international experience may be a desirable attribute for commissioners, but because it is difficult to objectively assess what constitutes significant international experience, that characteristic is not included in this assessment.

The nature of governance by commission requires that the commissioners work effectively together to accomplish the agency’s mission. Based on internal investigations, Senate oversight hearings, and numerous trade press reports, it is apparent that the commission ceased to function in a collegial manner during the latter stages of Jaczko’s 2009–2012 tenure as chairman. Ultimately, Jaczko resigned from the commission, and Macfarlane, his replacement as chairman, was generally praised for restoring a good working relationship among the commissioners. In fact, during the September 2014 confirmation hearing for Baran and Burns, much was made of the ability of both men, particularly Baran, to work well with others.

It is generally accepted that a good commissioner and, in particular, a good chairman, will have the ability to work in a collegial manner with peers and subordinates and will treat others in a respectful manner. This attribute, however, is not included in our list of characteristics due to the difficulty of determining the presence of sufficient collegiality in past and present commissioners. Any such assessment would be subjective and of questionable value.

Also inherent in the nature of governance by commission is the fact that the characteristics of individual commissioners cannot be considered in isolation but must be evaluated in light of the attributes of fellow commissioners as well. In addressing the wide range of issues that may arise in the NRC’s regulatory work, it would seem to be advantageous to have commissioners with a variety of backgrounds and experiences. For example, it might be considered advantageous to nominate an individual who brings experience with the naval nuclear program to the commission, but that advantage is minimal or even counterproductive if the commission already includes one or two members with nuclear navy experience. Similarly, a commissioner with commercial nuclear experience could bring the useful perspective of a licensee to the commission’s work, but having too many commissioners with an industry background would likely detract from the NRC’s reputation as an independent and impartial regulator.

A legal background is useful in carrying out the adjudicatory responsibilities of commissioners, but a commission made up entirely or predominantly of lawyers constrains opportunities for other important attributes. Given the highly technical nature of the NRC’s mission and regulations, the high percentage of technically qualified commissioners is understandable. While it is not essential that all commissioners have a strong technical background, when too many lack a scientific or engineering education and/or practical experience in the fields, it is very difficult for the commission to exercise its oversight role. The difficulty lies in assessing balance, another subjective evaluation.

NRC headquarters in Rockville, Md.

Looking at the trends

The review of characteristics of past commissioners and past chairmen reveals a wide range of pertinent experience in the group. Trends, including the following, can be discerned for some characteristics:

A technical background is historically very prevalent among commissioners, but only one of the four current commissioners has a technical education.

The percentage of commissioners with a political background has been increasing since the mid-1990s and is currently near its historical high of 45 percent. Of the current commissioners, 75 percent have a political background.

The influence of the nuclear navy was quite evident in early commissions and chairmen but has waned since the early 1990s.

The historical insulation of the commission from partisan politics appears to have come to an end. Six of the first 14 commissioners were unaffiliated with either major political party, but since 1986, there have been 24 confirmed commissioners, and only one, Burns, was an independent. Similarly, four of the first seven chairmen were independents, but of the nine chairmen since Carr, only Burns was an independent when confirmed.

During much of the NRC’s history, the commission was a very stable body. Most commissioners served to the end of their terms, and many served for more than a single five-year term; the overall average commissioner length of service is greater than five years. That stability has decreased lately, however, due to increased turnover from resignations. The average term of service for the four sitting commissioners is three years.

History shows that the safe and beneficial use of nuclear technology requires a competent, diligent, and independent regulator. In the United States, that regulator is the NRC, and it is governed by the commission. The commission is constantly evolving as members leave and new commissioners are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Commission turnover has increased recently, and among recent commissioners, a technical background is increasingly rare. The current trend is for commissioners to be nominated for a seat on the commission after working in a congressional staff role.