Atoms on the Grid! - Shippingport, 1957

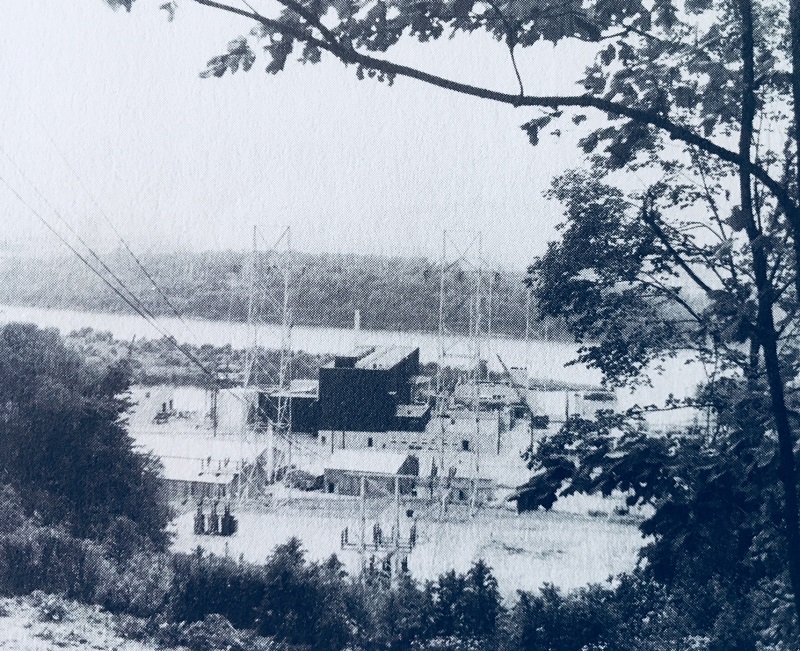

Shippingport Atomic Power Station as pictured in original press package; photo PR-19109

December 1957 would prove to be a month of firsts for the Shippingport Atomic Power Station; the plant had only recently been completed, and its new and novel reactor had only just achieved its first criticality on December 2nd. These were pioneering days, though - after all, the plant project had only been authorized in July 1953, some four and a half years earlier, give or take. Groundbreaking for the plant, after a selection process to decide who would partner with the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in the project happened on land provided by Duquesne Light Company in September 1954 with real construction work starting in March, 1955. Thus, the plant had been constructed in about two and a half years. In that spirit, operating the plant to see what it could do wouldn't wait for a battery of tests.

So, on December 18, 1957, after having operated the reactor and the plant's steam systems on and off for about two weeks, it came to pass that the first full-scale atomic power station to be built in the United States was synchronized with and connected to the grid. At first, the plant was operated at just low power levels. It didn't take long to complete some tests and reach full rated power on December 23, 1957, with the plant putting its full rated 60,000 kilowatts onto Duquesne's commercial grid. Atomic power had arrived in the United States.

Control Room, Shippingport Atomic Power Station. Westinghouse photo PRX-19630 from press release package on Shippingport in Will Davis collection.

So How Did It Do?

Shippingport Atomic Power Station was a hybrid, of sorts; it wedded a nuclear steam supply system (NSSS) intended originally for an aircraft carrier prototype plant, heavily modified, with a steam plant designed and built for it but designed and built by other firms than those involved with the nuclear portion. This arrangement was a result of the desire to have the AEC forge a relationship with private industry and utilities in the development of commercial atomic power. As a result, the nuclear portion and the steam plant portion were physically interconnected but were in at least some ways separate projects (having separate funding as well.) This would set the pattern for the demonstration plants the AEC would assist in constructing over the next decade.

Even with this duality the plant was well and solidly designed, and for the most part, quite reliable. Like any other pioneering project Shippingport did have some initial problems; it also had to shut down fairly often for testing, and often had to operate at low power for training. Still, the plant did quite well over its first few years.

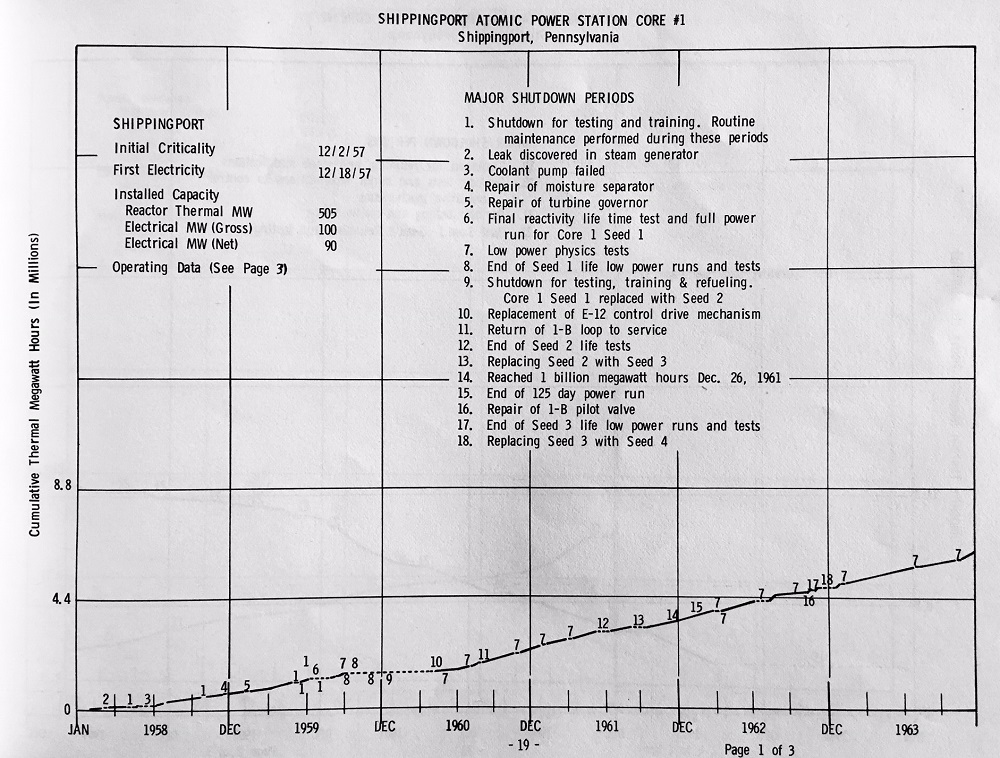

Our first illustration concerning Shippingport's early operation is the first of three pages covering the plant in "Operating History - U.S. Nuclear Power Reactors," WASH-1203-73, published 1973. This interesting and rare book graphically depicts the accumulation of actual megawatt-hours of nuclear plants in the US, with annotation to disclose reasons for power reductions and stoppages. As we can see, there were a few mechanical failures early in the plant's life - to be expected with new and developmental technology. By the end of this volume's reporting period in 1973 however, the average availability of the reactor plant was 99.5% while that of the total plant was 82.5% - an echo of the fact that steam plant, aux system and other problems were the causes of non-availability more so than the nuclear steam supply system.

Our first illustration concerning Shippingport's early operation is the first of three pages covering the plant in "Operating History - U.S. Nuclear Power Reactors," WASH-1203-73, published 1973. This interesting and rare book graphically depicts the accumulation of actual megawatt-hours of nuclear plants in the US, with annotation to disclose reasons for power reductions and stoppages. As we can see, there were a few mechanical failures early in the plant's life - to be expected with new and developmental technology. By the end of this volume's reporting period in 1973 however, the average availability of the reactor plant was 99.5% while that of the total plant was 82.5% - an echo of the fact that steam plant, aux system and other problems were the causes of non-availability more so than the nuclear steam supply system.

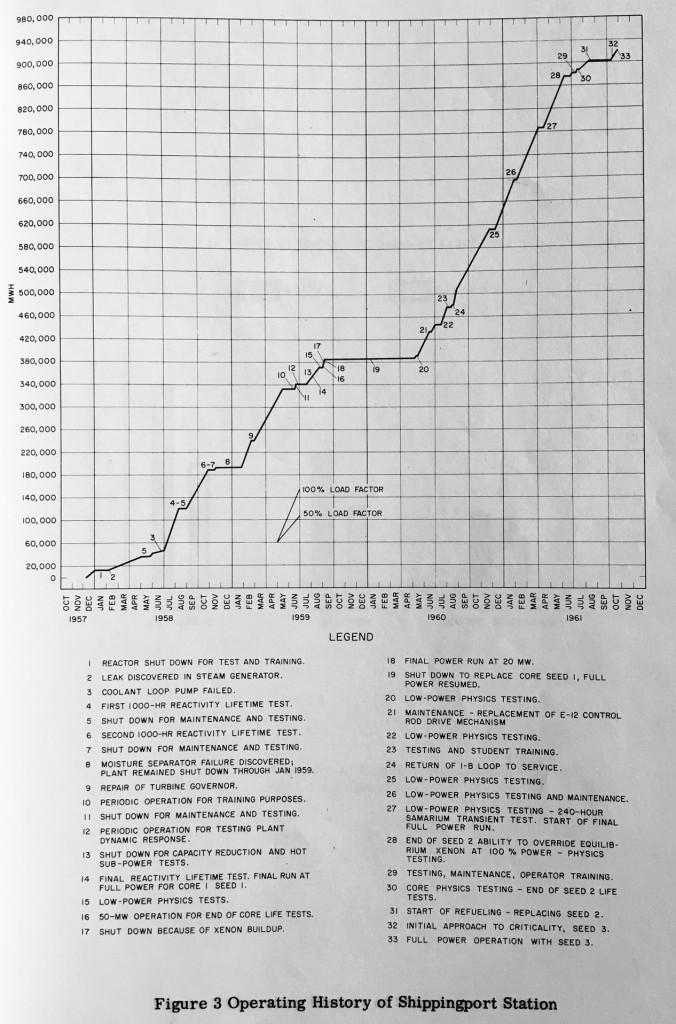

The next illustration, taken from "Shippingport Atomic Power Station Operating Experience, Developments and Future Plans" shows the early operation of the Shippingport plant in more detail. Click either photo to enlarge.

Operation of Shippingport

According to WAPD publication "Shippingport Atomic Power Station Operating Experience, Developments and Future Plans" (published December 1961) there were no actual large system disturbances during the first several years of operation of Shippingport which functionally tested its ability to respond to severe transients. However, the plant was actually tested in such situations by manual control and was found to meet or exceed all expectations and design criteria.

To wit:

"The simulated system disturbances showed that the reactor plant met all of its design requirements. These requirements included step changes of +15 MWe and -12 MWe; ramp changes of +/- 15 MWe at 3 MW/sec, and +/- 20 MWe at 25 MW/min. Manual control rod motion was used to maintain the magnitude of the plant temperature and pressure excursions during these load changes within desired limits."

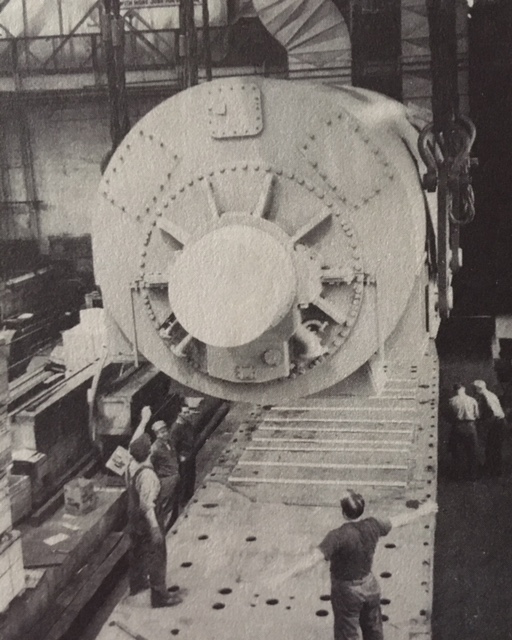

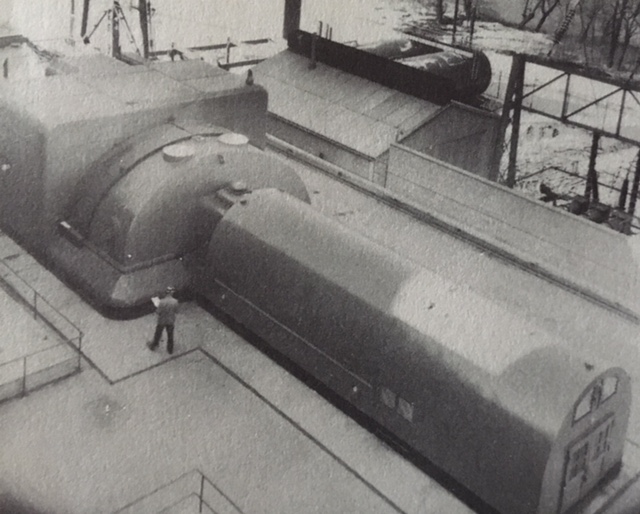

From Shippingport Press Package, photo PR-18318. "Generator for Shippingport Atomic Power Plant shipped from Westinghouse - Bound for Shippingport, Pa., site of the world's first full-scale atomic power plant devoted exclusively to serving civilian needs, this 100,000 kilowatt generator is prepared for shipment at the East Pittsburgh plant of Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Shown being lowered onto a flatcar by two traveling cranes, the 403,500 pound giant measures nearly 29 feet in overall length. When installed at the Shippingport site, the unit will not be housed in a building as is the conventional practice, but will operate in the open without the protection of walls or roofs - the first such installation of its type in this part of the country. Duquesne Light Company of Pittsburgh is building the electric generating part of the Shippingport plant and will operate the overall plant. Westinghouse, in addition to having built the generator pictured, is also designing and developing the plant's nuclear reactor under contract to the Atomic Energy Commission. The Shippingport plant is expected to be in operation in 1957."

"As a peak load facility the station followed all system load change demands in the power range. It also could be shut down and started up under controlled conditions at a faster rate than that of any conventional modern station on the Duquesne system."

Indeed, when compared with the modern Elrama Station Unit 4, a 175 MWe high pressure high temperature coal fired unit, Shippingport could go from zero output to 20 MWe in one minute; the Elrama station took 110 minutes to get to 35 MWe output.

Of course, the Shippingport plant also made long demonstration runs as a base load plant - two 1000 hour full power runs were made in 1958. Thus, the new atomic power station was operable either as a base load plant on the Duquesne system or as a peaker - a dual role not often ascribed to early nuclear plants but a role in fact inherent in the Naval origin of the NSSS, as well as other factors.

Shippingport Press Package photo PR-19857: "Shippingport Turbine Generator -- The nation's first commercial atomic-powered electric generating station can boast of many firsts; one of these is the installation out-of-doors of the 100,000 kw Westinghouse turbine generator shown above. Initially, the output will be 60,000 kw. This will be increased to full capacity later."

December 18 is an important day historically for nuclear energy because it was the first day that the much-heralded and highly anticipated Shippingport station, truly thought at the time to be a harbinger of a fleet of atomic plants, was placed on the Duquesne grid. Historic though it was, shortly Shippingport would actually prove itself in system operations and show that the payoff was as good as the promise; we have today's fleet of nuclear plants as a direct result of Shippingport's resounding success.

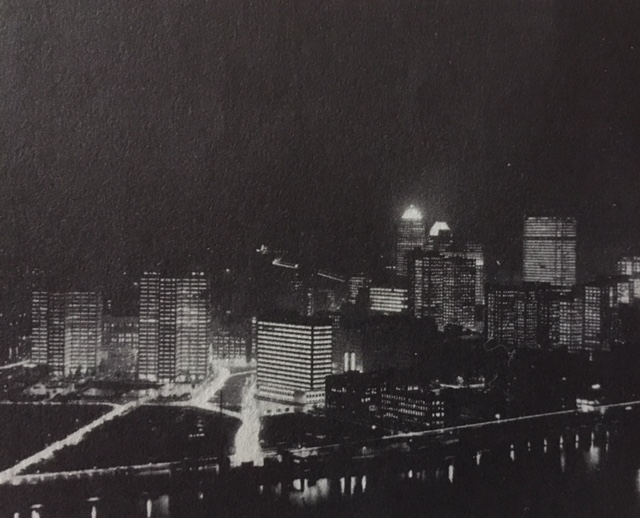

Shippingport Press Package photo PR-19658: "Symbol of Peacetime Power -- Symbolic of the historic event heralding the generation of electricity by atomic power from Shippingport, Pa. - site of the world's first full-scale atomic-electric generating station exclusively for civilian needs - are these lights of downtown Pittsburgh, Pa. Homes and factories of the Greater Pittsburgh area are receiving the electricity produced at the plant and transmitted through the Duquesne Light Company system. The Shippingport plant is a joint project of Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Atomic Energy Commission and Duqesne Light."

Feel free to leave a constructive comment for the author below. The author is also quite well aware that no atoms were actually transmitted to the grid by Shippingport; catchy titles require vague liberties with technical details at times.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.