New Reports? No, Old Facts. Nuclear Plant Construction Delay and Cost 1.

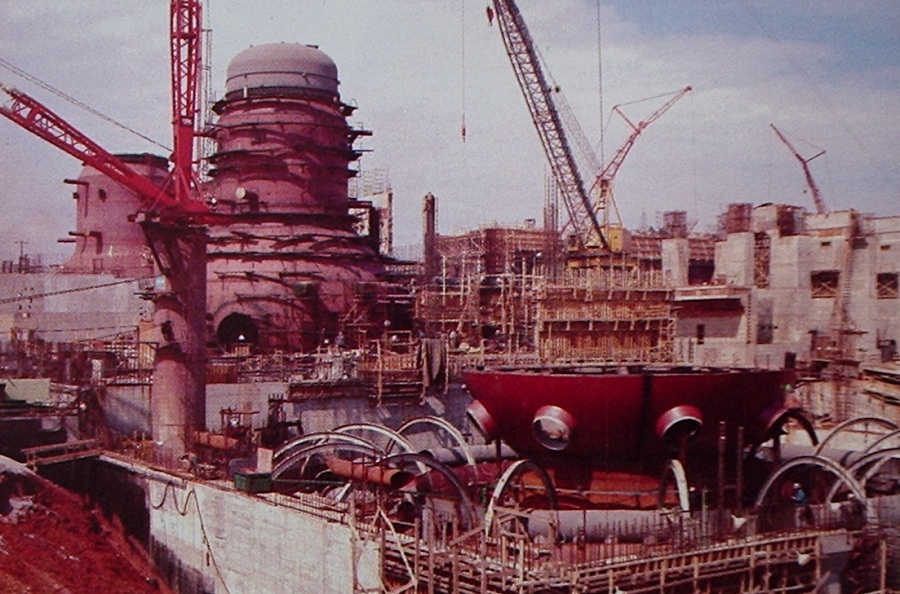

Photo showing the TVA Browns Ferry Nuclear Plant under construction at the end of the 1960's. This was TVA's first nuclear plant, which attained some notoriety for having been ordered in what previously had been considered "coal country."

Another, modern-day report has come out which in part discusses the problems encountered in nuclear plant construction - and discusses some suggested fixes for these. I welcome such research and reporting, but I have begun to wonder how many people realize that all of these studies have been done before and, more importantly, that the conclusions of those studies apply exactly to today's situation.

What situation is that? It's a situation where there is no established or "up and running" nuclear engineering and construction industry. Sure, there are firms with these things advertised over their doors, but we need to realize that nuclear plant orders here in this country halted in 1978, and construction dragged on only through the 1980's for the most part. There is a swath of time breaking that early design-build-redesign feedback loop so vital to success, but it's a swath that doesn't block some of the findings of that earlier, "First Nuclear Era" wherein nuclear construction started to come off the tracks.

While it's possible to review this earlier knowledge from many angles, for the start to this look back I'm going to consult a remarkable set of documents: A complete set of the annual US Atomic Energy Commission reports entitled "The Nuclear Industry." Each year a new volume was produced with a great amount of detail and analysis of the events of the year prior; each volume had the stated title plus a stated year of coverage. This series ran from 1964 through 1974, although it was not published for 1972. We can leaf through the pages of these important historic references to see what went wrong, when.

Early Years - No Problem, At Least Openly

It may surprise readers to learn that from the inception of this series (the 1964 volume) through the 1968 volume there's no mention of nuclear plant construction delays or cost overruns. There are a number of reasons for this, but frankly, many of these early plants were completed quickly as they were extremely simple even as they grew in size and output. Some of the plants, also, were ordered on a turnkey basis; Westinghouse and GE both offered, for just a couple years, a "turnkey" nuclear power plant which was ordered directly from them, and then built by them on a fixed cost basis. Overruns, if any, were absorbed by these companies and not widely discussed. Naturally, the firms had to hire architect-engineer and constructor firms like in any other large construction project but in the turnkey cases these firms worked for the reactor vendor, not the plant owner. Finally, a number of plants built during that time were AEC Power Demonstration plants built with AEC assistance in various ways and with the AEC responsible for the construction of the nuclear portion of the power plant.

It is important to note that the first nuclear plant ordered in the United States purely on an economic basis (that is, on the basis that it would be cheaper right then to operate and to fuel than a fossil plant) was Oyster Creek, which was ordered only in 1963. 1964 saw no orders at all for commercial nuclear plants, while 1965 saw seven units ordered. The flood gate opened in 1966 when 20 units were ordered; according to the AEC data for 1969, these 1966-ordered units were expected to come on line variously in 1970 (four years, six units), 1971 (five years, nine units), 1972 (six years, four units) and 1973 (seven years, one unit.) It's clear that a majority of these 1966 orders was expected on the grid, then, in five years.

1969 - First Reports of Delays

"The Nuclear Industry 1969" which, as stated earlier, actually covers the year 1969 (and thus was published early 1970) is the first in the series that mentions troubles with nuclear plant construction.

After mentioning that "1969 was a year of growing pains for the industry," the volume proceeds to open, for the first time, problems with nuclear plant construction on page 10:

"Serious delays in construction schedules of many nuclear power plants became evident during the year, along with substantial increases in construction costs."

The report continues with the mention that a number of utilities, balking at the delayed completion dates of some of the nuclear plants, had as a hedge quickly ordered either fossil fuel plants or gas turbine peakers to fill the gap in demand until the nuclear plants could be completed.

Concerning the actual magnitude of delays, the report tells us

"In early 1968, most utility executives expected that their nuclear plants for commercial operation in 1969 and 1970 would be on schedule. In contrast to the confidence expressed at that time, it now appears that only two of those 13 plants will be on the original schedule. The other 11 plants are experiencing delays of from about 2 to 13 months, due to many reasons, such as, late pressure vessel deliveries, regulatory requirements and proceedings, but predominantly due to the lack of experience in building nuclear plants and the inability to obtain experienced labor and craftsmen during the construction phase."

Nuclear plant cost rose 25 to 30 percent during this time, according to "The Nuclear Industry 1969," although it was pointed out that costs of fossil plants also rose considerably. Still, utilities continued to order nuclear plants based on the estimate that they would still be cheaper to operate over their full expected lives than coal, oil or gas fired conventional steam power plants.

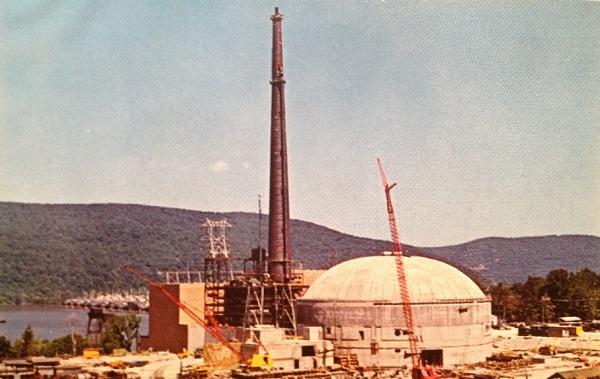

Consolidated Edison's Indian Point 1, ordered in 1955, did not come on line until 1963 for a variety of reasons; this was not called out by the AEC in its reporting, likely due to the early experimental nature of the plants ordered at that time. Photo in Will Davis collection.

Components Drive Some Delays Early

It was mentioned above that delayed delivery of reactor vessels was a contributor to overall construction schedule delays during the year 1969, and this fact led to the modern myth that component problems were part and parcel with nuclear builds. However, these problems were alleviated simply by market forces driving other companies into the field, leaving the initial impression as just a bad memory. For example, originally, in the United States, only Babcock & Wilcox and Combustion Engineering could factory fabricate reactor vessels for large commercial reactors; some smaller reactors had vessels made by other companies (A. O. Smith, Pacific Coast Engineering, Foster Wheeler and perhaps a few others) but the bulk of commercial power reactors in the light water class initially depended upon these two firms. While both scrambled to increase capacity at their plants, other vendors entered the fray to take up the slack; Chicago Bridge & Iron worked out a deal with GE to field fabricate two BWR pressure vessels per year completely on the site of a nuclear plant build, while other overseas vendors in Japan and Europe stepped in to assist with either complete PWR vessels or components (such as nozzle rings) for them. The field of turbine generators for nuclear plants experienced a similar "moment of alarm" due to supply which was then alleviated by Brown Boveri, English Electric and Allis-Chalmers entering the large, saturated-steam nuclear turbine generator market. (A-C had been in the steam turbine business until 1962 when it shut down that line, but decided to re-enter with Siemens partnership at the end of the 1960's when the demand for such machines proved solid enough to risk a new venture.)

In this quite natural way, industrial capacity rose to the (sustained) demand for these expensive, specialized products and alleviated large component-related delays overall except for a few special circumstances.

The Public Weighs In

The nuclear industry also began to face a new force in 1969 - public opinion. We find this to be true in the section "Civilian Power" of this same 1969 report. To wit:

"The decrease in orders and announcements of nuclear power plants during 1969 was, no doubt, partly due to a number of serious problems which began to appear around the end of 1968. Delays in construction schedules began to become apparent, with increased costs accompanying these delays. Also, certain segments of the public began to raise serious questions in regard to radiation effects and thermal effects of nuclear power plants and to intervene at the public hearings for some plants."

So, while the industry was experiencing what could rightly be judged as a period of rapid growth and the expected growing pains that come with it, it also had to face outside forces motivated by things other than economy and availability of power.

In defense of the business at large, though, the AEC added this on page 129:

".. Many of these delays are not unique to nuclear plant construction, but are characteristic of the construction difficulties experienced in general throughout the country. The delays in building nuclear plants are probably more pronounced, because of the higher degree of sophistication required on the part of craftsmen and the lack of experience by the architect-engineers and constructors in designing and building these new types of power plants."

Echoes of today - back in 1969.

In the next installment of this series, we'll finish our look at '69 and move on to the next year as the AEC further details complications. Later, we'll look at the opposition movement to nuclear plants as seen by the AEC itself. You won't want to miss any of this series!

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.

Feel free to leave a constructive remark or question for the author in the comment section below.

-3 2x1.jpg)