A Savannah Story

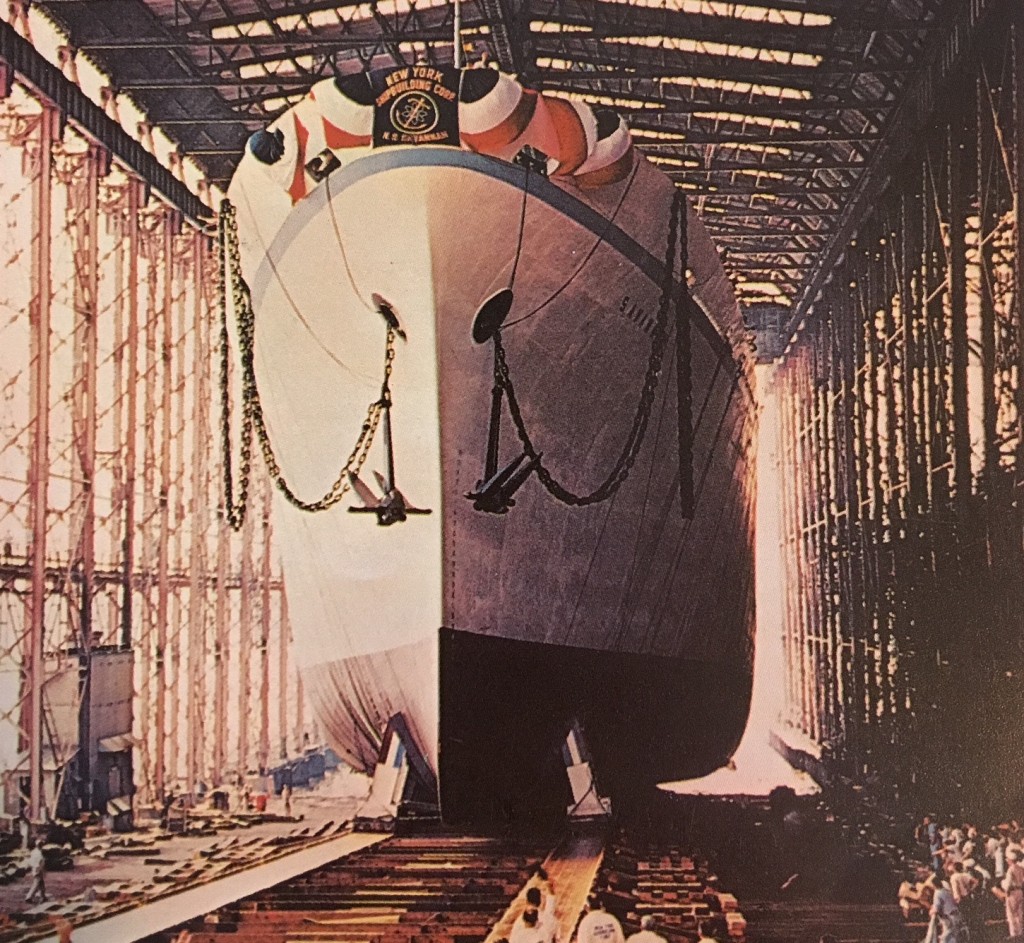

July 21 will bring with it another anniversary of the 1959 launching (shown above) of the only US-built nuclear powered commercial ship, the NS SAVANNAH. We've covered the ship fairly well here at ANS Nuclear Cafe over the years, so perhaps it's time for a story about the ship that's practically unknown. Did you know SAVANNAH was pioneering in another way .. with respect to uprates? That's right. The nuclear plant on SAVANNAH was uprated!

July 21 will bring with it another anniversary of the 1959 launching (shown above) of the only US-built nuclear powered commercial ship, the NS SAVANNAH. We've covered the ship fairly well here at ANS Nuclear Cafe over the years, so perhaps it's time for a story about the ship that's practically unknown. Did you know SAVANNAH was pioneering in another way .. with respect to uprates? That's right. The nuclear plant on SAVANNAH was uprated!

The Problem

When NS SAVANNAH was designed and constructed, it was built to a set of predetermined requirements for performance. Most importantly, the ship was required to produce 20,000 shaft horsepower (SHP) continuously, and 22,000 SHP on overload. The normal full power rating was achieved by the remotely operated throttle, whose controller was on the main control console; achievement of 'overload' power required an operator to manually open a valve on the HP turbine throttle body itself.

What happened during the early operations was this: It was discovered that the ship's electrical and "house" steam requirements were in excess of the original planned amounts; this placed a restriction on total power that the plant could devote to propulsion, with the result being that the 22,000 SHP contractually mandated overload was not at all times achievable without attempting to cut other loads.

The plant needed increased steam flow - and for that, it would need to have more power from the reactor. The reactor was originally rated for a maximum power of 70 MWt, with an operating limit of 69 MWt and a "normal" operating power of 64.7 MWt. If these limits were not addressed, the ship would not meet its original contractually stipulated performance.

The Solution(s)

As it turns out, the reactor protection analysis performed on the core by Babcock & Wilcox, the company responsible for it as well as the whole Nuclear Steam Supply System and the Instrumentation and Control, was in some ways far overdone (as was the design of the NSSS and core). Steady-state analysis of the core design by that company's engineers had been carried out, analytically that is, up to levels of ~114 MWt. What was required, then, in way of the core itself was not really a completely new RPA, but rather a restating of the approximation at a new, higher power level to the important limits (such as PCT or Peak Centerline Temperature of the fuel.)

It was shown that a new core operating power limit of 80 MWt would provide the required increase in thermal energy input to the two steam generators to then get the increased steam flow that would be needed to achieve the full 22,000 SHP requirement with maximum "house loads" on the plant. Flow in the primary would not be changed, but steam flow would increase from about 284,000 lbs/hr total to about 307,400 lbs/hr. The steam generators could take the increased flow - and the engines would just be producing their originally mandated power (at which they had been tested at the shops of De Laval Steam Turbine before ever being shipped to New York Shipbuilding for installation.) There would however have to be a few other changes made.

The comfortable lounge on board NS SAVANNAH at it originally appeared. Photo from brochure in Will Davis collection.

One change that had to be made was operation of the ship's main feed pumps. These steam driven pumps pushed water into the two steam generators; originally the ship was designed to operate at full power with one pump running, making the other effectively a standby. The new steam flow numbers (and thus feed flow) were too high for one pump; thus, to achieve full power, both feed pumps would now have to be running.

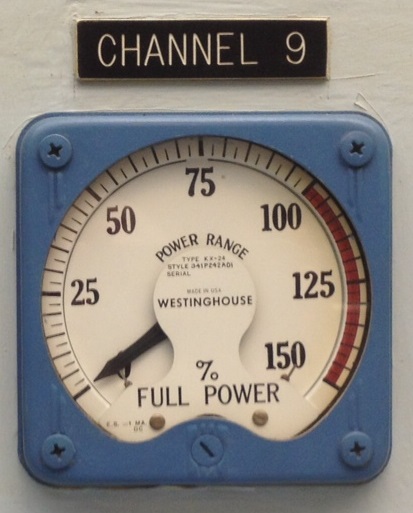

Reactor Power Meter, NS SAVANNAH. Westinghouse KX-24 D'Arsonval type meter. Photo by Will Davis.

The uprating had an effect on other systems as well, especially the emergency cooling system. This system, powered by a compact Fairbanks-Morse diesel (up at wheelhouse level) which hydraulically started on a loss of all A-C power on the ship, used a seawater heat exchanger to cool the plant. Naturally, this system was designed to remove decay heat only, since a loss of all A-C power would also scram the reactor. However, the system was designed to handle the heat load derived from a scram from 69 MW of power - not from 80 MW of power. It was shown in studies that simply operating the cooling system as it was but from the new core power rating would result in a lift of the primary relief in something like a half an hour. The change that was made was to double the seawater flowrate in the emergency cooling system; this put the temperature and pressure vs. time curves after a scram pretty much right on top of what they had been before.

Of course, a number of setpoints had to be changed - for example, the protection system was reset to give a high reactor power scram at 95 MWt. This was low enough to protect the core, and high enough to prevent scrams in situations where maximum power was required and some overshoot occurred on the up-power transient. Analysis showed that a high pressure reactor scram was required; this was added, set at 2000 pounds. Other changes were made as well to the reactor protection and control systems such as removal of the long-period fast insertion (intended to protect against excessive rod withdrawal below the point of adding heat, but which was too restrictive). These alterations and others were made when the ship was out of service for a period in 1964, and new specifications were issued at that time covering the changes.

"The Veranda" on board NS SAVANNAH as it originally appeared. The tables surrounding the dance floor had Lexan plastic tops which were internally illuminated. The large windows, facing aft, looked over a swimming pool and shuffleboard area.

The Result

The fact that this uprating never got any press to speak of is really a testament to the fact that it worked perfectly with no problems. What really paid off for the contractors, especially Babcock & Wilcox, was the original overdesign of important components that allowed for the uprating. Had these components not been overbuilt for the original specified power level by such a great amount there could well have been significant trouble in meeting the contractually required performance. As it was, though, the "spare no expense" thinking of the day paid off. The ship operated reliably for years after the changes.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account, @atomicnews is mostly devoted to nuclear energy.

Feel free to leave a constructive remark or question for the author in the comment section below.