What Next for SAVANNAH?

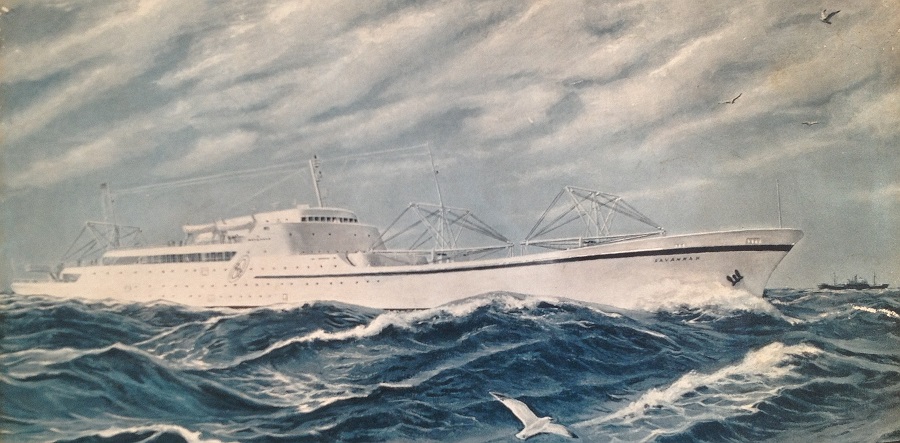

Illustration of NS SAVANNAH from Launch Ceremony Brochure in Will Davis' collection.

Observers were startled to learn in March that the Omnibus Spending Bill had included, in the budget for the U.S. Maritime Administration, the complete estimated amount required to perform the nuclear decommissioning of America's only commercial nuclear powered vessel, the NS SAVANNAH. While there had been some funding toward beginning the process in a previous year's budget, the provision of the full amount - not specifically requested by MARAD - was a surprise.

A SUCCESS, BUT NOT A SPARK

SAVANNAH was conceived at the end of the 1950's as the first of, it was hoped, a fleet of commercial nuclear powered ships. While during the 1950's the Congress had been pushing at times for either a nuclear powered bulk freighter (carrying oil, ore or coal) or a nuclear powered icebreaker, President Eisenhower understood what it meant to commercialize the technology. What was required was not just a "proof of concept" operational prototype, but also an international ambassador which could secure the agreements with other nations that would be required to allow US-flagged nuclear merchant ships to do business in their harbors. Without such agreements, nuclear ships would have nowhere to go - meaning that the technology wasn't truly commercialized.

In operation, then, during the first several years of its life, SAVANNAH did just that job, and did it admirably. Following a labor dispute (over the high pay of the engineering department) and a change of contract operators, the ship then ran for a number of years sans passengers. Freight was the order of the day; cargo tiedowns were added on the decks, and containers sat atop what had been a shuffleboard court.

In 1970, SAVANNAH was taken out of service. While various plans and schemes (and rumors) about the ship's fate circulated, the reactor was defueled in 1971. During the years 1973-1976, the nuclear power plant of the ship was rendered inoperable; steam pipes were taken down, the main coolant pumps were removed, and even the bull gear (largest gear in the reduction gears) was eventually taken out for use in another ship. Because of these alterations it was possible to amend the nuclear license for SAVANNAH to become "possession only" in 1976. Amazingly, the passenger areas remained intact as did the beautiful Veranda bar/lounge.

On board NS SAVANNAH, summer 2014. Photo by Will Davis.

IN STASIS FOR DECADES

The modifications to the plant to make it inoperable did not in any real way constitute what we'd normally think of as decommissioning - a process which, according to the PSDAR (Post Shutdown Decommissioning Activities Report) must be competed by 2031. The reactor vessel, steam generators, main coolant system and other smaller nuclear components still exist in the containment; there are also other areas to decontaminate and free release.

The ship variously was docked in Georgia, then in South Carolina at Patriots Point Naval Museum. After Hurricane Hugo's effects and several years of deterioration the ship was returned to MARAD hands and was docked in the famous James River Reserve Fleet off Newport News, Virginia. Here the ship stayed until moving to Baltimore in 2007.

At present, then, the characterization work begun under a smaller previous budget allocation will now swing into a much more serious effort. The nuclear steam supply system components will almost surely have to be removed; none has ever been released before to remain in place during a decommissioning although test bores show that the vessel itself would qualify as low level (Class A) waste. There is no schedule for the work as yet, as the announcement is still so fresh that there has not been time to develop one, much less select and hire all the contractors who will be required to perform the work. Early indications are that the work might be performed where the ship sits now.

It's hoped that the ultimate fate of the ship, after completion of the nuclear work, is a life as a unique museum or exhibit ship under private (decidedly non-MARAD) ownership. This notion is supported by the various historic designations the ship has been honored with (not least of which is designation by ANS as a Historic Landmark) but not guaranteed; sinking of the ship as a reef, or complete dismantling (scrapping to most of the world) are real possibilities. It's imperative then that effort be mounted beginning very soon to ensure that the ship is preserved if that is to be its fate. For example, it's not too soon to begin looking for a location and, probably, an integrated concept for a waterfront area for tourists and locals that incorporates the ship as an integral part.

THE MESSAGE OF SAVANNAH

It's especially unfortunate given today's focus on the pollution from merchant shipping around the world that nuclear ships didn't take off. The follow-on of sorts, OTTO HAHN, incorporated an integral PWR reactor designed from the experience with SAVANNAH. Both ships were highly successful; SAVANNAH had a power plant availability well over 90% and only ever suffered two significant mechanical failures during its decade of operation.¹ Still, this performance wasn't enough to offset uncertainties in the 60's and 70's about construction cost of future nuclear merchant ships, about insuring those ships, and about paying the highly qualified staff that would have been needed to run them.

Integral reactors - necessary to hold down power plant weight and size - are on the market again, right now, in 2018, and we're already seeing the flickering chance that more and more automation in power plant control will be embraced by the NRC. These factors, coupled with pollution considerations, might well spark a new generation of nuclear commercial ships. What's important to recognize, at least so far as SAVANNAH is concerned, is that the promise extended by that ship of a clean future has never been removed and stands just the same today as when the ship was conceived. What a shame it would be to begin building nuclear commercial ships once again just after the completion of the sinking or scrapping of this pioneering nuclear vessel.

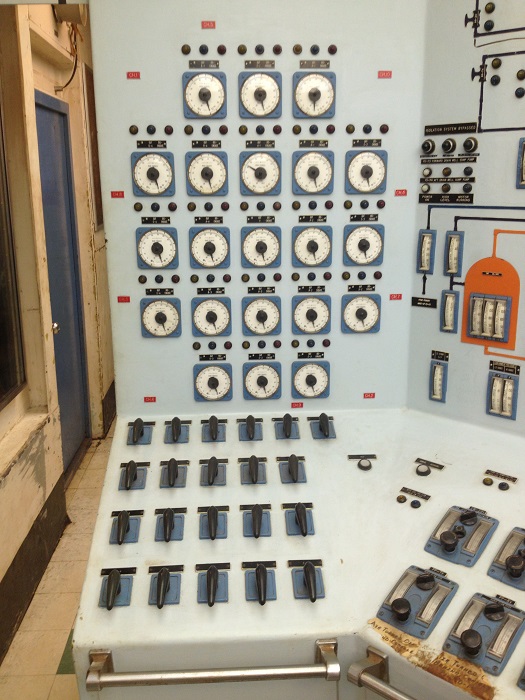

Rod control at the left of SAVANNAH's control panels. The ship used General Electric control rod drives like those found on early BWR's, but mounted on top of the vessel. As a backup, there was a contract with the Marvel-Schebler Division of Borg-Warner to provide electro-magnetic rod drive if the GE system didn't work out - but it worked quite well in service. Photo by Will Davis.

Notes:

1. Only twice did SAVANNAH have to suspend operations to take care of mechanical failures. The first event was the failure of the canned rotor main coolant pumps due to gas binding of the bearings; this occurred due to leakage of the pump cable penetrations during a pressurized containment leak test. Rigging out the motors was laborious, as was repairing the pump motors. Although the ship was built with four Allis-Chalmers pumps, two of these were put back in and two Westinghouse pumps were also added; Dymo tape on the reactor control panel to this day indicates which was which. Second, the ship experienced failure of the control rod drive buffer seals. These were wearing parts expected to fail. The condemning limit was reached while the ship was in New York; it was decided to transport parts and technicians there to perform the repairs rather than tow the ship to its maintenance base at Galveston, Texas (Todd Shipyards) - a good demonstration in light of the expected future fleet of nuclear ships which could not all be towed around the world for every sort of problem encountered.