Showdown at Shoreham

The story of the Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant on Long Island, New York was once well known in the industry and in utility circles; the plant, which took a very long time to construct and which faced considerable cost overrun, was heavily opposed by locals and in fact was never placed in operation. The specific details of the plant's long but non-operational history are, though, considerably more interesting and, in many ways both more revealing and more depressing than such a brief description implies.

SPARK OF OPPOSITION

According to US AEC WASH-1250 (1) "organized resistance to nuclear power plants first emerged in the period beginning about 1962" and was "regionalized in the New York City and California areas.." The opposition in New York was primarily because of the proposed Ravenswood nuclear plant, a Consolidated Edison project that was popularly opposed by former AEC Chairman David Lilienthal. According to WASH-1250 Lilienthal was quoted as saying that he would not continue to live in Queens, New York were the Ravenswood plant completed. "CANPOP" - or, the Committee Against Nuclear Power Plants - was one organization formed in the area to oppose ConEd's plan, and as is recalled by WASH-1250 "persons attending public meetings were greeted with literature headlined 'No Hiroshima in New York'."

Consolidated Edison never actually ordered the plant, it turns out; the company pulled its application for the Ravenswood project before the licensing process with the AEC had moved very far along. The outcome though was that nuclear power was on the radar screen of local activists who, apparently, did not seem to care about rising energy prices generally in the region or pollution from fossil fired power plants.

SHOREHAM SEES THE SAME

It's not a surprise then to discover that just a few short years later in the mid-1960's when Long Island Lighting Co. (LILCO) announced and then ordered a nuclear power plant to be constructed on the north end of Long Island, there was a ready base of opposition.

Shoreham was ordered in 1967, with the AEC authorizing construction in 1970. That meant that Shoreham, like so many other contemporary plants, was about to run into a regulatory buzzsaw of changing requirements, moving targets and of course compliance with NEPA as a result of the Calvert Cliffs decision. That in part helped ensure delays and, with those, cost overruns. But it was the organized opposition to the plant that pushed the experience from the frustrating to the farcical.

According to the brochure "The Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant - An Overview," which was published by LILCO in 1982 the first public hearings on the project were scheduled for March, 1970. The story LILCO tells in the publication is exceedingly frustrating:

"Meanwhile, an intervenor group, calling itself the Lloyd Harbor Study Group, was formed. This group asked for and obtained six months of delay in the opening of the hearings.

The hearings finally opened in a school gymnasium in Rocky Point on September 2, 1970. In the ensuing weeks, months and years of interminable hearings, Long Island was treated to a new phenomenon in the conduct of what was supposed to be an austere, administrative proceeding. The process was supposed to be one in which the evidence was submitted, facts examined, issues resolved, relevant cross examination conducted, and, as a result of this, a license would be issued or the Company could have been required to modify its designs. As a practical matter, the AEC did not even allow applications to get as far as the hearing process if their staff did not believe the plants to be licensable. The Shoreham hearings were very different. The plant's opponents turned the hearing into what they called 'multi-media confrontation,' designed to attract press attention and spur the development of an anti-nuclear movement.

This took the form of bringing in a total impostor, claiming to be an expert with a PhD and an MD; endless days of reading aloud from newspaper and magazine articles; interminable 'cross examination' without regard to whether it contributed to an intelligent determination of issues relevant to the proceeding; and an imaginative variety of other devices to delay the proceeding and attract the attention of the press."

The only good thing to come from this deliberate and embarrassing circus put on by the anti-nuclear operatives was that, according to LILCO, "the agency (NRC) tightened up its rules so that other companies would not be subjected to similar sabotage of the licensing process."

Control room, Shoreham; from LILCO brochure.

MAJOR COST DRIVERS HIT SHOREHAM

LILCO described six considerations in the plant's delay and cost overrun other than organized opposition. Briefly paraphrased, these were:

1. Changing regulations caused the owners to be unable to get jobs bid on fixed price contracting, forcing cost-plus contracting except at the very end of construction.

2. Inflation shot up to 10.3 percent per year in the 1970's and, worse, inflation in the market for construction supplies went up to around 300 per cent in some cases.

3. Interest rates shot up in the 1970's as well, "to levels which would have been almost unthinkable a decade earlier" which seriously drove up the cost of loans. LILCO said that over a third of the Shoreham project cost was interest on (loans for) construction work in progress, which it could not recover from ratepayers at that time.

4. Rapidly changing regulations required "innumerable" plant design changes and unfortunately affected parts and structures already installed. The tearout of installed components often disturbed other installed components so that costs snowballed on the changeouts.

5. Several factors contributed to cause late delivery of scheduled parts and materials to the plant. Project managers were then often forced to install what they had on hand rather than wait for all the parts to perform work in the originally specified order (a failing that sometimes happens in project management when percent completion is the only metric of importance.) This led to various "best of the bad choices" construction process changes in terms of winging the construction schedule and procedure while maintaining the requisite level of quality and integrity of work required by the NRC.

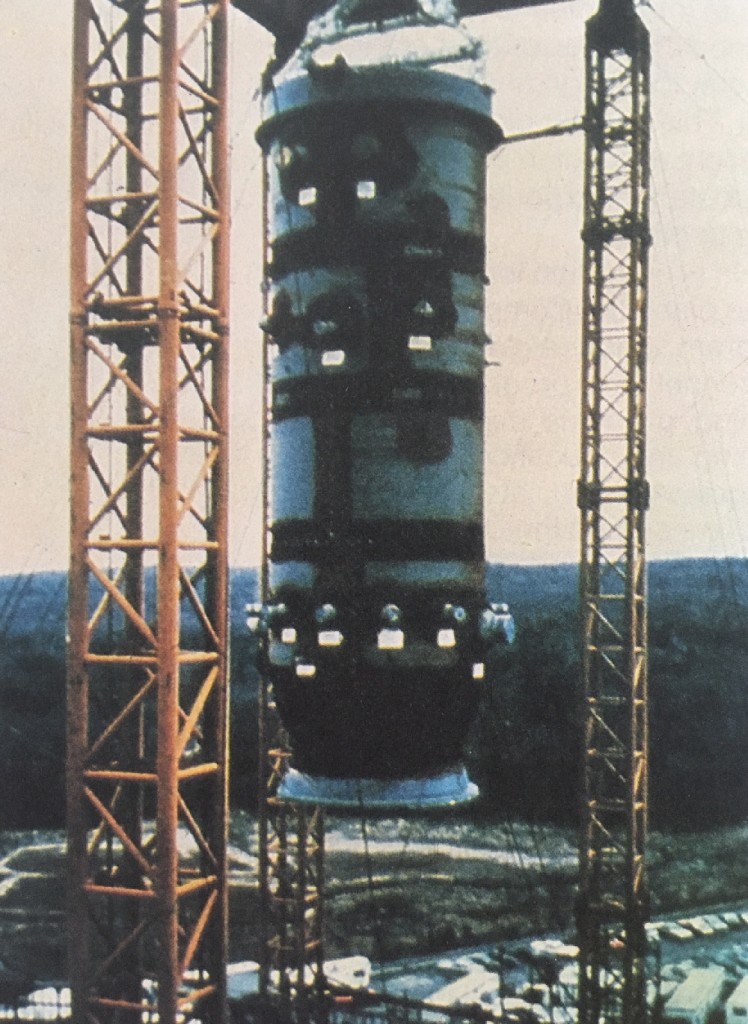

6. The containment was completed fairly early in the process but continuously changing equipment requirements, driven by changing regulations, led to numerous changes of, or additions of, equipment inside that already-crowded structure. According to LILCO, "While the engineers were able to design these components into the structure, their installation was a cumbersome and costly process."

COMPLETED BUT NEVER COMMERCIAL

Shoreham was finally declared complete in 1985 and preparations were made to load fuel and start up. Adding insult to injury, the plant had experienced incredibly bad luck in 1983 when one of its diesels broke its crankshaft (kicking off the whole TransAmerica - DeLaval Diesel debacle that affected numerous plants nationwide when it was discovered that all suffered from torsional vibration problems.) The plant was actually operated at 5% power, but was destined ultimately never to operate as intended.

New York Governor Cuomo, father of the present Governor, negotiated with LILCO to shut down Shoreham permanently in 1989; with the Legislature of New York having passed the Long Island Power Association Act to set up an authority to take over Shoreham and decommission it, the fate of the plant was sealed. Before a decade more had passed, Shoreham was decommissioned; the nuclear steam supply system was removed, and the plant could never operate as a nuclear plant (although there were plans to power the original turbine with steam from a fossil plant.)

Shoreham had ultimately, according to the New York State Comptroller, taken about $5.6 billion to construct; according to LIPA, the decommissioning (taking only two years, from 1992-1994) cost about $181.5 million. Although the entire region continued to experience increasing generating costs, nuclear was ultimately not to be allowed to stabilize those costs for New Yorkers. Uneducated fear and party line politics, assisted by numerous external factors, had won.

Today the site sits almost unused; while there are some small power generation and distribution assets on the site, the power output is nothing like that which would have been available for Shoreham. Further, had the plant been completed it would only have been in operation at this point for about 30 years - meaning it would have a long time to go given the general trend to push nuclear plant lives out to 60 years and perhaps beyond. The plant itself is an off-limits shell occasionally visited by curiosity seekers (a dangerous trip, given the unmaintained nature of the empty hulk) which stands as a testimonial to past days of hope and promise on one side and activist obstruction on the other. In a world now looking at needing vastly more electric power to meet needs and reduce pollution, the Shoreham tale can be a cautionary exercise for both sides if viewed soberly.

(1) WASH-1250; The Safety of Nuclear Power Reactors (Light Water Cooled) and Related Facilities. Final Draft, US Atomic Energy Commission July 1973. This report never made it beyond this final draft version, and was instead replaced by the very different and much more analytically oriented WASH-1400 Reactor Safety Study so well-known in nuclear energy.

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account is @atomicnews

Will Davis is a member of the Board of Directors for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar. His popular Twitter account is @atomicnews

Feel free to leave a constructive remark or question for the author in the comment section below.