A Change of Plans at Brookwood

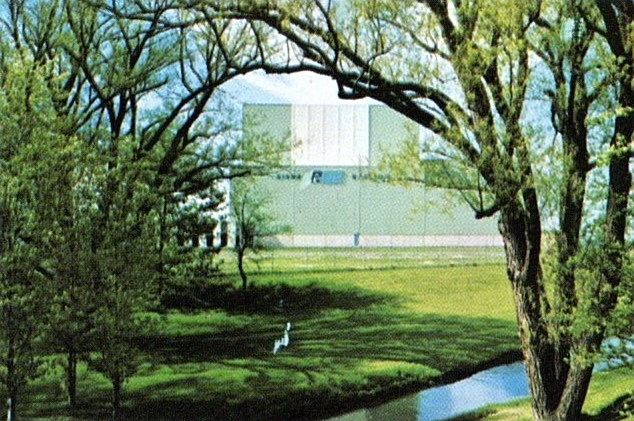

R.E. Ginna Nuclear Plant, built for Rochester Gas & Electric Company in a beautiful natural setting. Photo from brochure in Will Davis library.

By the middle of the 1960's, Robert Emmett Ginna had already spent over a decade taking part in, and in no small part championing, the development of what we would today call advanced reactors. His efforts contributed to the development of breeder and high temperature reactors, yet when it came time for his own utility to construct a nuclear plant, it made a sudden reversal to construct a very conventional pressurized water design.

Beginnings

The early days of nuclear power planning in this country included a number of large groups of utility companies and interested manufacturers and shippers who realized that the development costs for nuclear power would be huge. These groups formed official promotional and developmental organizations, whose names quickly became well-known in those early days. Ginna himself, representing his own employer, Rochester Gas & Electric Co., played a vital part in several of these early organizations.

Two of these organizations took part in designing and constructing the world's first commercial breeder reactor nuclear power plant. Atomic Power Development Associates, Inc. was formed as a nonprofit corporation under New York law, with a goal of developing "atomic power into a commercially practicable means of electric power generation." Rochester Gas & Electric was a member of this corporation, along with 29 other utilities and 12 industrial manufacturers and shippers. The power plant they funded, which became the Enrico Fermi Atomic Power Plant near Detroit, included a nuclear portion designed by the Power Reactor Development Company, which included 21 utilities and manufacturers. RG&E was again among the members of this group.

Another different organization, known as High Temperature Reactor Development Associates, Inc. focused on gas-cooled reactors. In this group, Ginna himself acted as President. No less than 53 utility companies across the United States joined together in this group, whose efforts culminated in the 1958 proposal to the Atomic Energy Commission to construct a high-temperature, gas-cooled commercial nuclear plant on property owned by Philadelphia Electric Co. This plant eventually became known as the Peach Bottom Atomic Power Station.

RG&E Bids In Itself

Given all this, it seemed only natural that Ginna, as chairman of Rochester Gas & Electric, would steer that company toward building a nuclear plant when it required increased capacity. The company's first proposal for a nuclear plant followed right along in the footsteps of Peach Bottom.

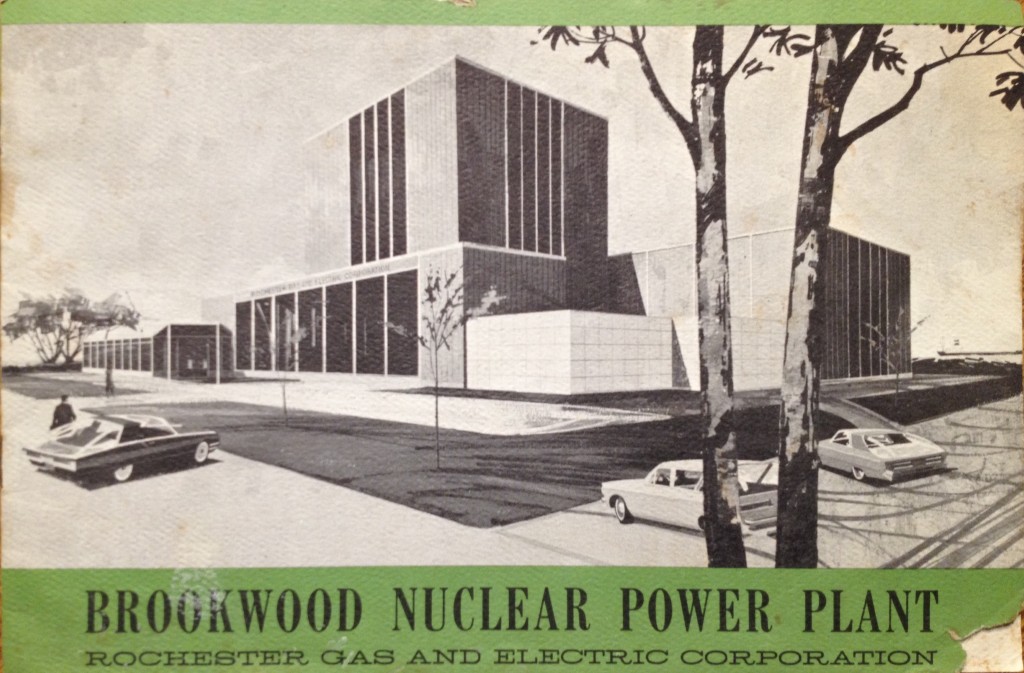

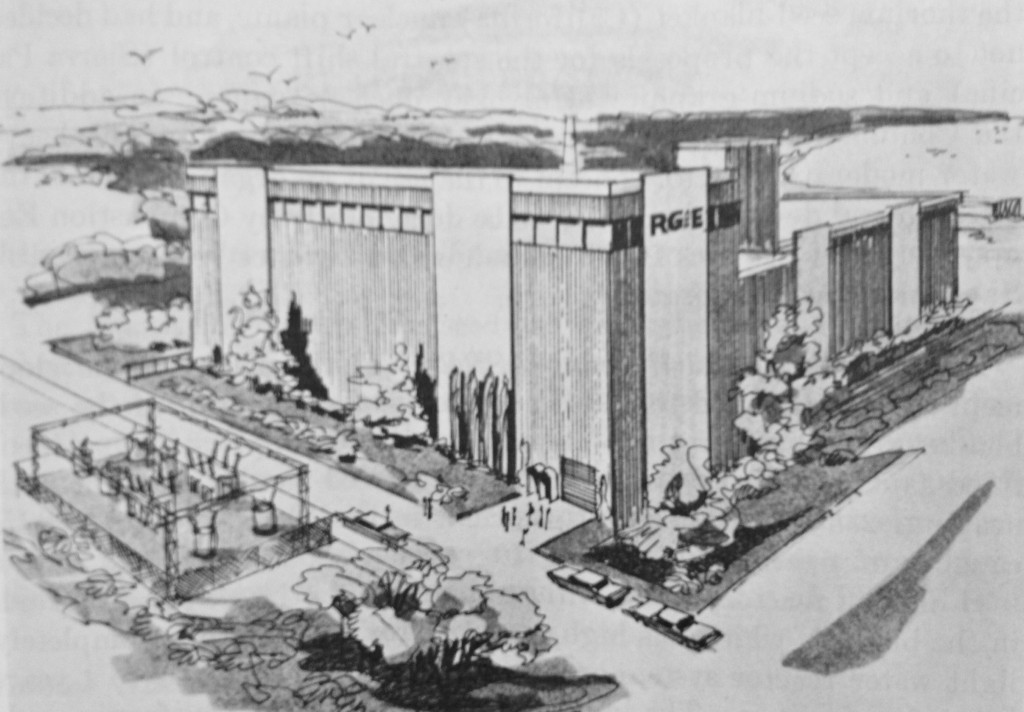

Proposed High Temperature Gas Cooled Reactor nuclear power plant for Rochester Gas & Electric. Shown in 1964 AEC Annual Report to Congress, in Will Davis library.

In response to a general request by the Atomic Energy Commission for proposals in advanced reactor designs, RG&E and General Atomic (the vendor behind Peach Bottom) made a proposal in 1964 to construct a high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) plant on property owned by RG&E in New York. The proposal to the AEC included what was then known as a "turnkey" contract, in which a reactor vendor would construct the complete nuclear power plant, with the utility essentially "taking the keys" at the end of the construction process (although in reality the owners of turnkey plants had to be more involved than this description might imply). General Atomic, according to the proposal, would construct for RG&E a 260 MWe HTGR nuclear plant at a site about 19 miles east of Rochester, NY. The September 1964 acceptance of the proposal by the AEC formed the basis of what were to have been negotiations on pricing, and work on AEC licensing of the plant.

Turn Key Yes; HTGR, No

The RG&E HTGR project must certainly go down as one of the shorter-lived nuclear plant proposals, because the next year, in 1965, the RG&E board of directors made the solid decision to order a new power plant, and made the decision (based on economics) that it would be nuclear. However, instead of pursuing negotiations on the HTGR plant, the utility instead accepted a proposal from Westinghouse Electric to construct, also in turnkey fashion, a much more powerful 450 MWe pressurized water reactor nuclear plant. Gilbert Associates was retained as Architect-Engineer, while Bechtel Corporation was hired to construct the plant. The contract called for the plant to be financed wholly by RG&E with no AEC assistance, and there was no AEC fuel-charge waiver issued. The plant was truly commercial and on its own feet. RG&E backed out of the HTGR proposal and would have the new PWR plant built on the same site; it was announced and ordered as the Brookwood Nuclear Power Plant.

As announced, the project cost was estimated at $74 million; the nuclear plant was actually ordered in 1965, and was scheduled to produce its first electricity in 1969. Actual construction of the plant began in April 1966; construction was very rapid, and on November 9, 1969 the completed nuclear plant achieved its first criticality. The first electric power was generated on December 2, 1969. However, an important change had occurred.

Robert Emmett Ginna, who had championed nuclear power and steered RG&E through several early and significant contributions right through to owning its own nuclear plant, had retired from the company in 1968, having served it in various capacities since 1927. To honor Ginna and his contributions, the RG&E board made the decision to change the name of the plant to what it is today - the Robert Emmett Ginna Nuclear Power Plant.

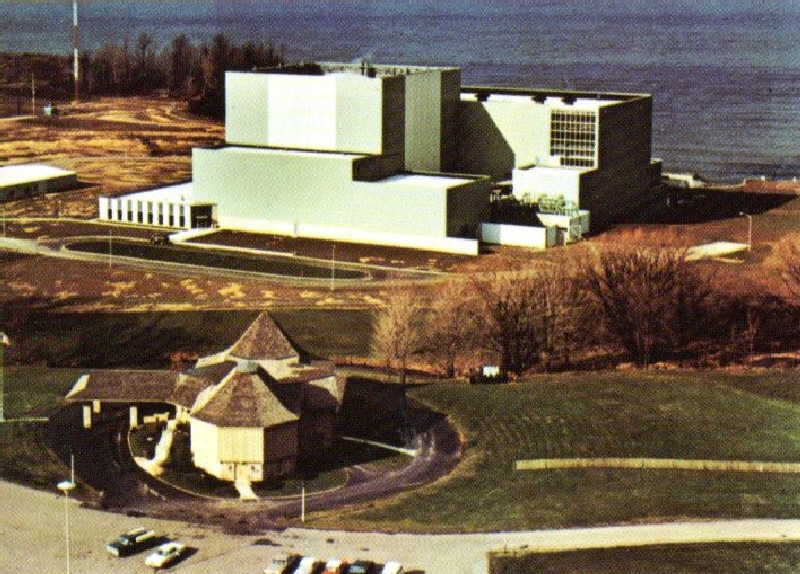

R. E. Ginna Nuclear Power Plant. In the foreground is the Brookwood Science Information Center. From brochure in Will Davis library.

One part of the project retained the original name - the Brookwood Science Information Center, located (as were so many such facilities across the US) right next to the nuclear plant, opened in 1966 and within a couple years was hosting 60,000 visitors a year.

Brookwood Science Information Center, adjacent to R. E. Ginna Nuclear Plant. From brochure in Will Davis library.

Postscript - What of the HTGR?

The high-temperature gas-cooled concept did not die off, as we know - in fact, it barely missed a beat. Another group stood in the wings, having conducted negotiations at the same time as RG&E, that would effectively rescue General Atomic and the gas cooled reactor. Advanced Reactor Development Associates, a consortium of 11 investor-owned utilities, had begun discussions in 1963 along similar lines to RG&E. As a result of two years of study, one of the consortium members, Public Service Company of Colorado, ordered a 330 MWe HTGR nuclear plant in 1965. This plant, unlike Ginna, was to receive considerable assistance from the AEC; up to $40.9 million was authorized for general developmental costs, along with a fuel charge waiver good up to $6.4 million. Public Service of Colorado was slated to contribute $57 million for the plant.

Fort St. Vrain Nuclear Generating Station. From brochure in Will Davis library.

Fort St. Vrain, it is well known, was not ultimately a successful proposition. Ginna, on the other hand, according to U.S. AEC data from 1973, had a reactor availability factor of 95.27 percent and an overall plant capacity factor of 87.35 percent. Although Ginna would have its share of troubles over the years, the plant survives to this day - keeping alive, at least in part, the memory of the contributions of Robert Emmett Ginna and those early-day nuclear industry groups who pushed for the future, willing to break their picks, so to speak, to advance the cause.

Will Davis is Communications Director and board member for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and on the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar.

Will Davis is Communications Director and board member for the N/S Savannah Association, Inc. He is a consultant to the Global America Business Institute, a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, and he writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is also a consultant and writer for the American Nuclear Society, and serves on the ANS Communications Committee and on the Book Publishing Committee. He is a former U.S. Navy reactor operator and served on SSBN-641, USS Simon Bolivar.