Cuban Agreement Awakens Memories of Juragua

The announcement made this past September 27 that Russia had signed an agreement with Cuba to cooperate in the advancement of nuclear technologies raised in some quarters the notion that Cuba might again aspire, eventually, to investigate nuclear energy. The details of the original effort to give nuclear energy to Cuba were remembered in some places; we will take a brief look at that effort and what became of it.

Juragua and the VVER-440

It might be remembered today that upon the collapse of the Soviet Union, a wide effort began to have the earliest of the Soviet designed PWR or Pressurized Water Reactor plants shut down everywhere throughout Europe. This design of nuclear plant, the V-230, was troubling to Westerners because (like the RBMK-1000 plant that experienced an accident at Chernobyl) there really was no containment in the event of an accident.

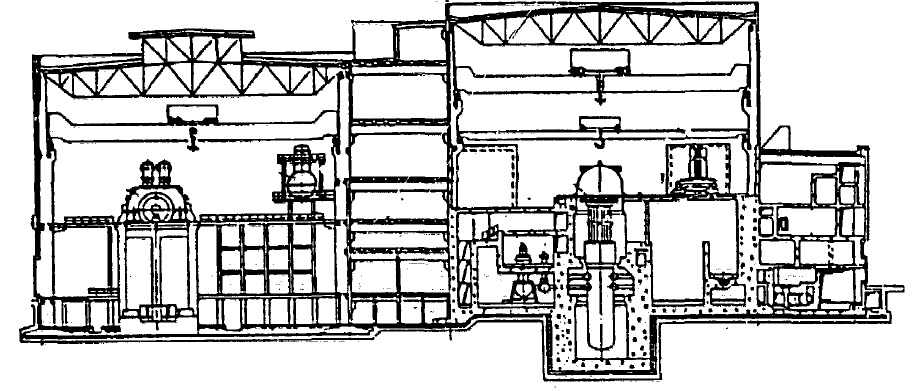

VVER440 V230 nuclear plant design; illustration courtesy Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The V230 plant design nuclear plant (shown above) was always built in pairs, with two reactors each rated roughly 1375 MWt, and four 220 MWe turbine generators (two to a reactor). The net 440 MWe output of each nuclear unit or "block" gave rise to the VVER-440 designation (VVER is an acronym that stands, roughly, for "water - water power reactor") very generically applied to these plants. However, the power rating is far less important than the overall plant design -- a designation derived from the particular design bureau and project which develops each detailed plant design.

In the illustration above the reactor can be seen at the right; the vessel is supported in concrete but the rest of the building is more or less like a general industrial facility. The turbine hall on left houses all four turbine generators for the two reactors and is open inside end-to-end.

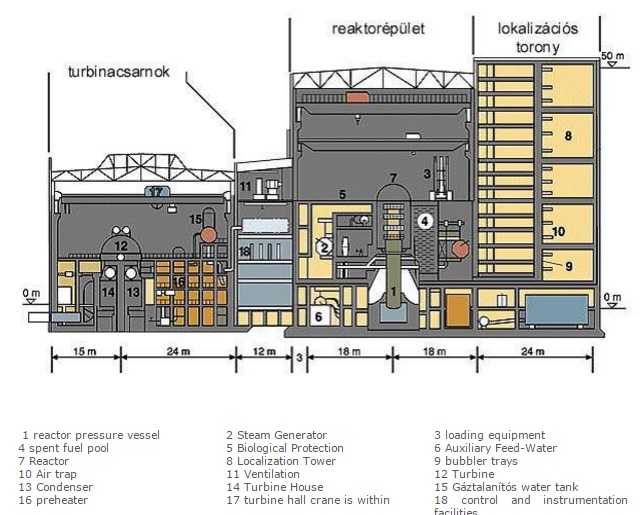

The V230 was replaced, somewhat confusingly. The V213 plant design, which took a step toward Western standards by improving containment for the reactor and by including a large "bubbler" tower, seen at the right of the illustration below, connected to the steam generator spaces. It was intended to contain and condense gases in the event of an accident.

VVER440 V213 plant design courtesy Atomeromu, Hungary (Paks Nuclear Power Plant.)

The Soviet Union developed some other derivations of these designs - for example, the V270 for Armenia, which has extra consideration for the seismic conditions there. However, that plant is not vastly different to those shown above.

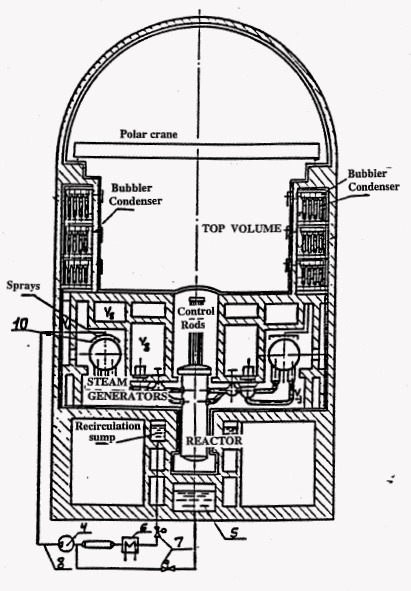

What was really different though in the VVER-440 range was the plant that the USSR designed for export, or construction well outside the Soviet bloc. This design, the V318, included a decidedly western style cylindrical containment building for each reactor. A cross section of the V318 type containment is seen below, and the similarity to Western style PWR plants is remarkable.

VVER440 V318 containment building, courtesy ORNL

This advanced style of VVER-440 nuclear plant was that selected for construction in Cuba was also, it was reported at the time, selected for construction at at least one other location inside the USSR, but construction was not proceeded with. Thus, Juragua was the only plant of its type.

The containment of this plant was supplemented by other systems not found in the V213 plant design that preceded it. For example, the containment had both active and passive pressure suppression installed in the containment to mitigate potential accidents. The plant was also designed from the outset with high seismic loads in mind throughout. Emergency Diesel Generators (EDG) were kept well separate from each other to prevent common failure. Emergency Core Cooling was installed in multiple systems, intended to handle requirements of a double ended main coolant pipe shear; for example, a passive injection system capable of reflooding the core to two thirds height in 40 seconds was fitted, which sourced borated water from four tanks (only three being actually required.) There was also a low pressure injection system with three duplicate injection trains 120 degrees apart around the containment to inject borated water to a depressurized main coolant system. Further, there was a separate high pressure injection and cooling system, also in triplicate. The plant's six main coolant loops were isolable from the reactor using remotely operated valves, as a further added safety feature.

In fact, the almost incredible (for Soviet plants, for that day) assumption was made in the safety design that the maximum credible accident occurred simultaneous with the maximum credible earthquake and seismic load; this is what led to the remarkable safety system redundancy and the use of the massive containment. There were many other improvements (too numerous to list here) but it suffices to say that the nuclear power plant under construction in Cuba beginning in the 1980's was nothing at all like the VVER-440 plants anywhere else, and was exponentially safer by design.

COMECON builds; alone, Cuba fails

Construction of the project got underway in 1982, although the agreements that led to the plant being built in the first place go all the way back to 1972 when Cuba became part of the Soviet-bloc economic cooperative known as COMECON. Without going into detail, it will simply be noted that under the original arrangements the Juragua plant was being built for Cuba by Soviet experts (although Cubans were also heavily involved) while Cuba's exports to the USSR were simply taken in. There was, more or less no specific accounting going on in which Cuba was paying dollar for dollar the construction costs, as "trade credits" were being exchanged.

Originally this plant, sited at Cienfuegos, was planned as a four-unit site but construction of only two units was first authorized because Cuba did not yet need the energy of a four reactor plant. Juragua was part of a general plan of the time to industrialize Cuba, and for this naturally there would be a large demand for electric power, but only eventually, so that construction of Units 3 and 4 could wait. Unit 2's construction began somewhat later that Unit 1, not starting until sometime in 1985. Construction in this location, the most remote yet selected for a Soviet plant, went slowly.

Before the first unit was complete came the rapid decline and then, in a historical sense, very rapid collapse of the COMECON arrangement and the Soviet Union itself in the 1989-1992 time period which more or less cut off all of the broad economic and technological aid programs that were being branched out from the Soviet Union through the Communist nations, and of course to Cuba.

Reports began to circulate at the end of 1991 that economic aid for the Juragua project was to be ended by Russia; at that time Cuban officials stated their intent to somehow attempt to continue the project. In fact, in February 1992 Cuba announced that it had completed a radioactive waste treatment facility near, but not in, Havana which was built in part to handle wastes from the unfinished power plant. By September the Cuban government was forced to admit that support for the project from their former masters had indeed ended, and that all work at the site had halted. Fidel Castro, perhaps largely symbolically, fired his son who had been directing the construction project on the Cuban government's behalf, but this change could not possibly affect the cutoff of cash, expertise and equipment from the former suppliers.

At the time of cessation of work in 1992 it was being reported in the trade press that construction of Unit 1 was approaching 80%, while Unit 2 was a much more modest 15% complete. The high level of completion for Unit 1 though related, actually, only to "civil works" portions of the plant. Not nearly all of the primary plant equipment was yet installed, and much of the secondary plant equipment was not even in Cuba yet. (The reactor vessel, steam generators and turbine generators for Unit 1 were in Cuba.) Thus, on a more modern or Western schedule Unit 1 was in fact not actually 80% complete.

Still, the project had been something of a source of pride for the Cuban government and for a number of years it attempted to figure out deals with Russia (now handling by itself the export nuclear plant business) to get the plant finished. At the time work was stopped, Russia said that it would take about $2 billion to finish the plant, and that instrumentation and control would have to be purchased from a Western vendor. (Siemens was approached.) Later estimates by the Russians were as low as $1 billion, but were only rough estimates of what would need to be new arrangements. Even in 1995 deal making continued; Russia at that time agreed to an equipment grant for Cuba to the tune of $30 million to buy secondary plant equipment for Unit 1, and stated at that time that it felt the plant could perhaps run by 1999. The site had been in a controlled upkeep mode with regular stops by Russian technicians since then, and material deterioration had been prevented. None of these talks of course were to come to fruition; Cuba could not pay for, and really in fact did not need, this nuclear power plant (in terms of electric power demand) particularly with none of the other programs to build up Cuba with cash, supplies and personnel from the now-collapsed USSR still operating.

Today, the Juragua Nuclear Power Plant site is essentially abandoned. Occasionally, photos or videos are seen of the site after curiosity seekers enter for a look - and the site looks very much like a number of abandoned nuclear construction sites in the United States (such as TVA's Hartsville A and B sites.) There is perhaps only the most remote chance that the plants there could ever be finished now, after years of exposure to the elements and total lack of upkeep - but could the site be re-used for a new plant? Perhaps; it was originally intended for four units, so indeed there may be room there if, once again, Cuba decides that it has aspirations for nuclear energy. Considering the recent agreement with Russia, it just well might. And we may see that Cuba's nuclear energy history has only been paused.

Sources: Nuclear Engineering International Magazine (February, September, November 1992 and December 1995). "Accident Sequences Simulated at the Juragua Nuclear Power Plant." Juan J. Carbajo, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1998.

-3 2x1.jpg)