The Atomic City

In 1959, a small community in Ohio completed a lobbying effort to bring a modern marvel to town-a nuclear power plant. Piqua, a town of less than 20,000 people, took its place on the broader news map, and set its sights on the stars. The journey would stop short of the citizens' dreams.

Energy

Piqua had something of a history by this time when it came to electric power, because it had divorced itself from outside commercial supply and "done the job in house." In the early part of the century, after electrification came to town, the city had purchased electricity from Dayton Power & Light. The city began to feel by the early 1930s that the prices charged by DP&L were far too high. Repeated negotiations lowered, then raised, and then lowered the rates until the ground swell by the Piqua town folk was large enough to take matters into their own hands. The city built a municipal power plant and, in 1933, severed outside electric connections. The plucky Ohioans had proven that even in the height of the Great Depression it was possible to make investments and advances, and no small amount of pride was taken in their achievement. Post cards showing the power plant were widely printed and sold.

Atomic possibilities

The US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) made several rounds of investment in nuclear plants of various designs in the late 1950s and sought to build prototype plants in actual, working locations spread around America-so long as the sites were logical and safe. Rural nuclear plants-smaller units powering outlying communities instead of large cities-were a feature of this program (at least in effect, if not in deliberate purpose or design) and a number of smaller designs were right for smaller electric systems. Of course, as with today, there were dozens of hopeful designers but unlike today many more dozens of hopeful locations. After significant lobbying work was performed by Piqua city officials, the AEC selected Piqua to host a new organic-cooled type of reactor that had only been built in test form prior to this time.

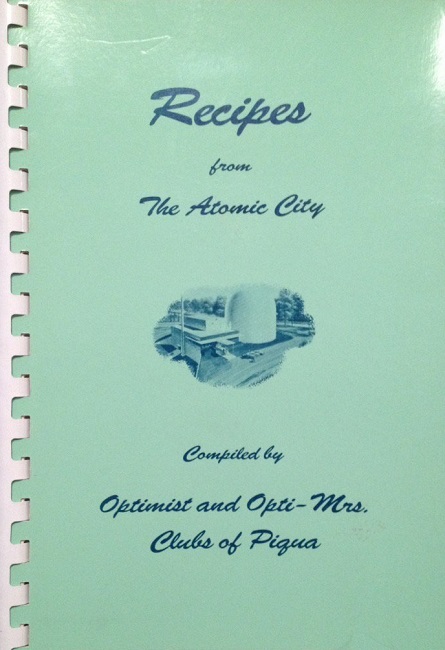

Newspaper clippings of the day (provided by Piqua Municipal Power from its archive) clearly show the immense interest of the city. Many articles were printed before any actual construction even began, and the updates on the progress of the plant were frequent. Very early in the process the city began to think of itself as something special for having won the chance to host a nuclear plant, and began calling itself "The Atomic City." The name spread around not only the local papers, but to other publications as well.

"Recipes from The Atomic City." Piqua Ohio Optimist and Opti-Mrs. Clubs cook book, mid 1960s. Courtesy Will Davis.

Progress

As the Piqua Nuclear Power Facility (PNPF) began to take shape, it seems that reporters constantly visited the site for photos and information. Changes in staff at the plant, new features being installed, inspections, and other normally somewhat mundane things made the newspapers. A look at the papers of the day (too lengthy to include here) shows that the townspeople believed all sorts of good things would come their way after this modern marvel was in their midst. And many of them did.

After the plant was operational, it was decided by the AEC that the PNPF would be placed experimentally under the supervision of the International Atomic Energy Agency. This brought interested foreigners from many locations to the city to inspect the plant, of course to the delight of the locals-and, of course, these visits also made the news. The city felt as if it were on an international stage, and of course in a narrow consideration it was.

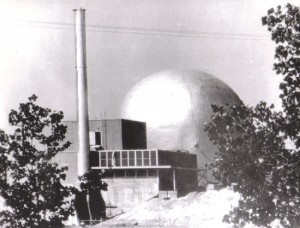

The new plant was right in town, where it could be seen. And yet, it supplied not electricity but steam-steam that was piped over to Piqua's earlier energy achievement, the original Municipal Power building, where it was used to run the steam turbines already located there. The blue-painted containment dome stood in contrast to the early '30s brick architecture of the nearby power plant, and one could say easily that the Alpha and Omega of Piqua's energy history stood hand in hand, joined by a short bridge across the Great Miami River.

The Piqua Nuclear Power Facility is seen on the right of this PR photo; the Municipal Power Plant is up river, on the other bank. Photo in Will Davis collection.

Realities

As with many other early nuclear plants, some delays were encountered as technology was being developed and in some cases "designed as you went." However, after its initial startup, the plant experienced very little trouble for over a year. The novel organic-cooled reactor, which operated at a low pressure thanks to its terphenyl coolant (a heavy oily substance known under the commercial name of "Santowax"), operated as had been expected and predicted. However, later in 1965, the reactor began to experience problems with sticking control rods; this and other concerns led to the reactor being shut down in January 1966 to examine the causes.

It was discovered that a large deposit of polymerized coolant had developed in somewhat of a doughnut shape inside the core. The coolant was subject to breakdown by radiation, and was generally maintained at about 80-percent purity by bleeding off coolant and adding coolant continuously. The broken down, or "cracked", coolant had polymerized and caused the blockage. Disassembly of the reactor and preparation of new procedures to flush and clean the system were prepared, but these were not things that had been prepared ahead of time and so took time.

The process dragged on for almost two years until Piqua's city officials had enough; they ventured to the AEC headquarters to find out just when the plant would restart, and at what point ownership of the nuclear plant would be turned over to the city. Instead, at that meeting, the officials were shocked to learn that the AEC had decided to drop its organic-cooled reactor research and that the Piqua Nuclear Power Facility would be permanently shut down and decommissioned. The shock of this decision registers clearly in surviving newspaper clippings of the day. Piqua's AEC meeting contingent had hoped for a triumphant return or at least answers but were instead sent back with what felt like doom; the Atomic City was no more.

Legacy

Today, the once-marvelous PNPF structure still sits in its spot on the river bank, with meager remains of the nuclear plant entombed in its basement while the upper floors are used daily by the city to store materials and park vehicles. After the AEC and its nuclear vendor, the Atomics International Division of North American Aviation, were done clearing out the nuclear plant and the control and support equipment, Piqua turned the property over to the AEC (now the Department of Energy) and agreed to maintain the property while using it for city business and work.

Piqua celebrated its bicentennial in 2007, and saved newspapers and flyers of the day include reference to many of the "good old days" of the past. The Atomic City era is viewed in these with some nostalgia, but with even more regret-regret that the plant did not continue to operate, yes, but perhaps even more (and maybe unintentionally) with regret for how much of the city's self-image had been propped up, and then dashed, based upon this single project. Perhaps that's Monday morning quarterbacking. The city itself could not have been prouder to host, help construct, staff, and operate a nuclear plant than it was in the 1960s. Perhaps for today's world, it is that desire and pride that is best remembered-and perhaps even envied.