Eisenhower's Atomic Power for Peace – The Civilian Application Program

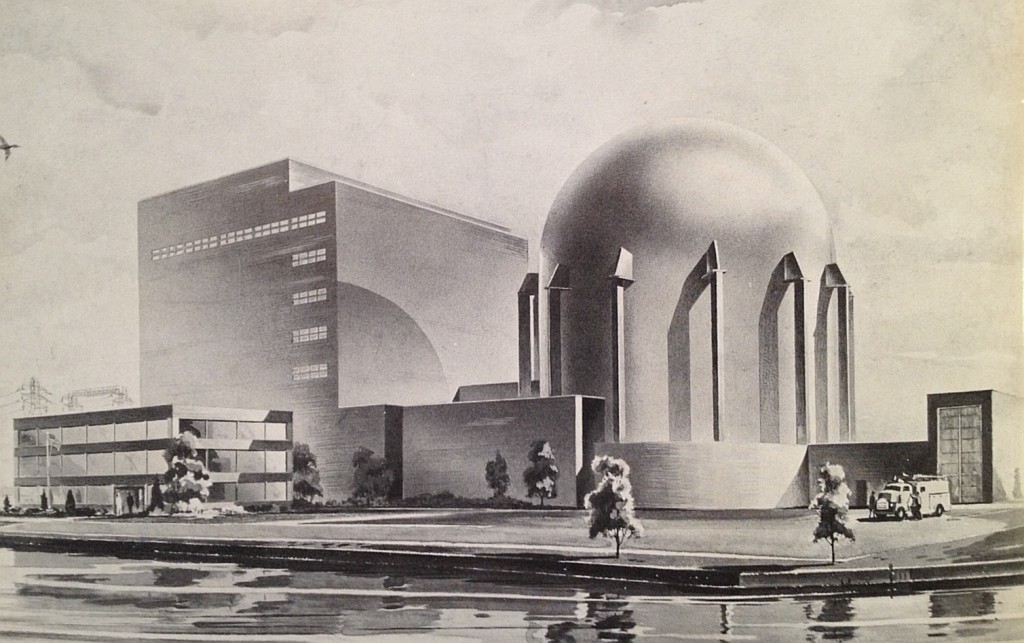

Futuristic illustration from 1955 Progress Report, Atomic Power Development Associates, published March 1956. This would become the Enrico Fermi Atomic Power Plant.

President Eisenhower's momentous Atomic Power for Peace speech to the United Nations in December 1953 included the bold statement: "It is not enough to take this weapon [a metaphor for atomic energy, specifically as weaponized only] out of the hands of soldiers. It must be put into the hands of those who will know how to strip its military casing and adapt it to the arts of peace." With that, he effectively launched the civilian nuclear power business as we know it today-of course, it having since undergone many changes and evolutions. What's little spoken of today is what happened before and after this speech.

President Eisenhower was only partly correct in his implication at this point of the speech that atomic energy had really only been weaponized up until that time; by then, a number of reactors had been built that generated power, including the EBR-1 in December 1951 (at the National Reactor Testing Station, Idaho), the HRE-1 at Oak Ridge in February 1953, and significantly the STR prototype at the Naval Reactors Facility, Idaho, in March 1953. (He of course knew of these developments quite well, as we shall see momentarily.) What he proposed to enable next had far bolder ends-the transfer of the knowledge of nuclear technology to those who could build commercial nuclear plants, medical research and treatment facilities, facilities for food preservation-in short, all the sorts of things that nuclear technology does so well today. Considering the development of a naval nuclear propulsion plant, nuclear energy was, even as a fledgling technology, perhaps ready to answer the call first.

There were already considerable efforts behind the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), but in fact the real start of what might be today recognized as the program to develop power reactors had begun back in 1948 when the AEC established a Division of Reactor Development. In this organization's years prior to Eisenhower's new paradigm, a number of advances were made that directly affected the ability to jump-start civil power reactor development. For example, not only had the AEC established a National Reactor Testing Station in Idaho where it built and tested a number of concepts, it had developed a type of fuel plate known later quite generally as "MTR type," which would in fact become one of the first standardized, off-the-shelf fuel elements offered to reactor designers (this would be by Sylvania-Corning). Studies undertaken in the early 1950s were either military-only with AEC funding, or else part of a 1951 invitation from the AEC to potential reactor vendors and engineering firms to study dual-purpose reactors for both weapons material production and power production. (While this concept spread widely later in the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, only one of this type was ever actually built and operated in the United States-the NPR, or New Power Reactor, at Hanford.)

The year 1948 was not, however, the first by any stretch that any entity in the United States had seriously considered nuclear energy for production of power. In 1939, the US Naval Research Laboratory began a study into the use of atomic energy to propel ships. This initial effort resulted in developing the thermal diffusion technique for enrichment of uranium, but nothing else concrete because the war effort soon dictated that all effort be focused on development of a weapon. However, the Navy picked right up again immediately after the war, when a team of Navy officers was assigned to study the prospective Oak Ridge helium-cooled power reactor. (One of these men was Captain Hyman Rickover.) Shortly, a contract to more formally study this project was given by the Navy to Allis-Chalmers-but the reactor project was cancelled very rapidly. Development of the Navy program is fairly well known after this point, leading to the already-mentioned prototype and another, less successful prototype using liquid metal coolant.

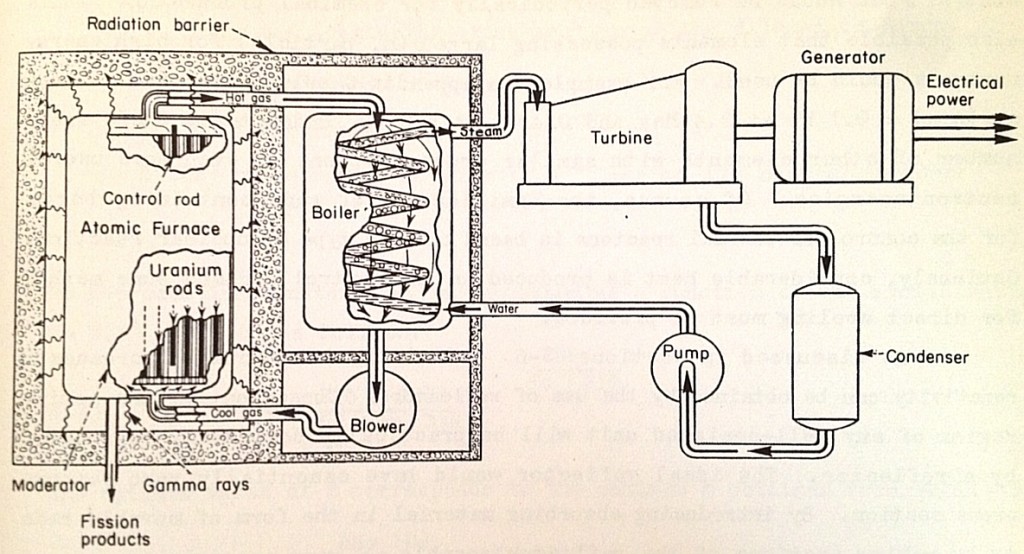

Diagram of projected gas cooled power reactor as perceived in 1947, to have been built at Clinton Laboratories at Oak Ridge (later known as Oak Ridge National Laboratory). The gas coolant was not yet determined, but helium, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide were being considered. Fuel rods would have been movable for control. Illustration from "The Science and Engineering of Nuclear Power," edited by Clark Goodman. Addison-Wesley, Cambridge Mass., 1947.

What was necessary now to launch a civilian-based nuclear industrial complex was to release the stranglehold that the US government and military had on all materials, research, experience, and personnel relative to nuclear energy. That restriction was well known to Eisenhower who shortly after (February 17, 1954) issued an official message to the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy laying out particular details and recommendations for a way forward. In that message, he said in part, referencing the limitations of the original Atomic Energy Act of 1946;

"...The practicability of constructing a submarine with atomic propulsion was questionable in 1946; 3 weeks ago the launching of the USS Nautilus made it certain that the use of atomic energy for ship propulsion will ultimately become widespread. In 1946, too, economic industrial power from atomic energy sources seemed very remote; today, it is clearly in sight-largely a matter of further research and development, and the establishment of conditions in which the spirit of enterprise can flourish."

This letter was the first actual executive communication-seen first naturally by the powerful Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, which oversaw all things nuclear-related in the legislative branch-that would lead to amendment of the original Atomic Energy Act to allow transfer of what had originally been government/military information, as well as materials to the civil sector. It would also lead directly to a great deal of documentation covering security requirements necessary to ensure that information was both properly transferred out of government/military auspices (by either straight declassification, or else by controlled transfer to entities entitled to possess it) and then, in the case of controlled transfer, properly controlled by those who had legally obtained it.

Eisenhower detailed his approach to the policy alterations that he felt would enable the development of a domestic atomic energy industry later in the same document of February 17, 1954. To wit:

"Domestic Development of Atomic Energy.What was only a hope and a distant goal in 1946-the beneficent use of atomic energy in human service-can soon be a reality. Before our scientists and engineers lie rich possibilities in the harnessing of atomic power. But, in this undertaking, the enterprise, initiative, and competitive spirit of individuals and groups within our free economy are needed to assure the greatest efficiency and progress at the least cost to the public.

Industry's interest in this field is already evident. In collaboration with the Atomic Energy Commission a number of private corporations are now conducting studies, largely at their own expense, of the various reactor types which might be developed to produce economic power. There are indications that they would increase their efforts significantly if the way were open for private investment in such reactors. In amending the law to permit such an investment, care must be taken to encourage the development of this new industry in a manner as nearly normal as possible, with careful regulation to protect the national security and the public health and safety. It is essential that this program so proceed that this new industry will develop self-reliance and self-sufficiency."

Most of what Eisenhower laid out in this concept came true-although many would observe that the self-sufficiency part was the longest to iron out, since few corporations (acting as either vendors of reactors or as architects, engineers, or constructors of atomic power plants) were initially willing to risk such large projects entirely on their own.

Eisenhower's specifically-delineated recommendations for legislative amendment were as follows:

1. Relax statutory restrictions against ownership or lease of fissionable material and of facilities capable of producing fissionable material.

2. Permit private manufacture, ownership, and operation of atomic reactors and related activities, subject to necessary safeguards and under licensing systems administered by the Atomic Energy Commission.

3. Authorize the AEC to establish minimum safety and security regulations to govern the use and possession of fissionable materials.

4. Permit the AEC to supply licensees special materials and services needed in the initial stages of the new industry at prices estimated to compensate the government adequately for the value of the materials and services and the expense to the government in making them available.

5. Liberalize the patent provisions of the Atomic Energy Act, principally by expanding the area in which private patents can be obtained, to include the production as well as utilization of fissionable material, while continuing for a limited period the authority to require a patent owner to license others to use an invention essential to the peacetime applications of atomic energy.

This mention of patent legislation was followed by a statement that the corporations that already had access to privileged information and material could conceivably build a monopoly based on patent rights, squeezing out any potential new entrants. Eisenhower wished to prevent such an outcome by ensuring at least for five years that patent information was shared until "industrial participation in the utilization of atomic energy acquires a broader base." There stands much evidence in the record that there was considerable opposition to the AEC having unilateral rights to patents granted in this field, as surely would have been expected-and would be today.

Eisenhower wasn't the only person at that time who believed that it was not only important but essential that atomic energy information and technology be made widely available, and that generation of electric power by atomic means eventually become profitable enough to stand alone without massive government subsidy because of the great good it could do. He was also not the only person who knew what it had done to date. Henry D. Smyth, a member of the AEC, made the following remarks in the closing of a speech he delivered to the American Institute of Chemical Engineers in March 1954:

"To establish a nuclear power industry in this country will be a great achievement. If power becomes cheaper and more plentiful, our material standard of living will be raised. In other countries, the effect may be even greater. By the accident of history the first use of this great new discovery has been in the development of weapons of war, weapons of appalling magnitude. The nations of the world have today the means to destroy each other. They also have, in this same nuclear energy, a new resource which could be used to lift the heavy burdens of hunger and poverty that keep masses of men in bondage to ignorance and fear. Toward this peaceful development of nuclear power we have, all of us, a high obligation to work with all the ingenuity and purpose we possess."

The die had been cast; the United States was going to launch an atomic energy program, and the civil sector was going to do a lot of the heavy lifting. While private corporations were certainly interested, few would continue to participate only in self-funded studies (such as that in 1951 for dual-purpose reactors) when there was little or no chance of financial return. Something concrete would have to be established, and opportunity for real work presented. It would not be long.

"Perspective drawing of atomic energy power plant," from Pacific Gas & Electric/Bechtel Corporation report to the US Atomic Energy Commission, 1952. This is one of the dual purpose (power and weapons) studies performed for the AEC prior to Eisenhower's speech as described in the article; this consortium considered water cooled thermal and sodium cooled fast reactors for this plant, each rated 500 MWt. From Reports to the US Atomic Energy Commission on Nuclear Power Reactor Technology, US AEC, May 1953.

In our next installment, we'll look at the AEC's first Five Year Plan for Reactor Development. On July 31, 1953, the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy asked the AEC to come up with "an outline of the objectives it seeks to achieve in the field of reactor development over the next five years and of its program for accomplishment of these objectives." This plan would be integral with the Civilian Application Program, and together these two would shape the course of early commercial nuclear energy development in the United States.

Sources for this article include:

ATOMS FOR PEACE MANUAL-A Compilation of Official Materials on International Cooperation for Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. 84th Congress, 1st Session, Document No. 55. July 1955 US Government Printing Office.

THE ATOMIC ENERGY DESKBOOK. John F. Hogerton. Reinhold Publishing, New York 1963.

NUCLEAR PROPULSION FOR MERCHANT SHIPS. A. W. Kramer. Division of Technical Information, US Atomic Energy Commission, 1962.

REPORTS TO THE ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION ON NUCLEAR POWER REACTOR TECHNOLOGY. US Atomic Energy Commission, May 1953.

US SUBMARINES SINCE 1945. Norman Friedman. US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1994.

Sources for photos are quoted in photo captions.

_________________________

Will Davis is a consultant to, and writer for, the American Nuclear Society; an active ANS member, he is serving on the ANS Communications Committee 2013-2016. In addition, he is a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, is secretary of the Board of Directors of PopAtomic Studios, and writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is a former US Navy reactor operator, qualified on S8G and S5W plants. He's also an avid typewriter collector in his spare time.

Will Davis is a consultant to, and writer for, the American Nuclear Society; an active ANS member, he is serving on the ANS Communications Committee 2013-2016. In addition, he is a contributing author for Fuel Cycle Week, is secretary of the Board of Directors of PopAtomic Studios, and writes his own popular blog Atomic Power Review. Davis is a former US Navy reactor operator, qualified on S8G and S5W plants. He's also an avid typewriter collector in his spare time.