Why don't we "mothball" shutdown nuclear plants?

In May 2013, the United States lost a perfectly functional and well-maintained nuclear power plant, the Kewaunee Nuclear Power Plant. Last week, Entergy announced that it would be shutting down a second such plant, Vermont Yankee, after its current fuel load has been consumed. In both cases, the owners indicated that the plants were no longer economical due to market conditions; namely, the low price of natural gas, the presence of subsidized renewable energy suppliers that can pay the grid to take their power and still receive revenue for every kilowatt-hour generated, and an insufficient market demand for electricity in the markets where the plants were attempting to sell their output.

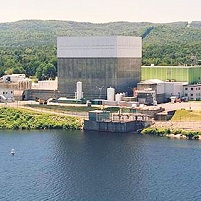

Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant

Under similar market conditions, conventional power plant owners might decide to shutdown the plant but make provisions to ensure that the plant could be restored to service if needed, or if the market conditions change by either increasing revenue opportunities, lowering operating costs, or both. However, in each of the nuclear power plant cases under discussion, the owners decided that their best course of action was to announce a permanent shutdown with the concurrent action of giving up the plant operating license. In both cases, the plant operating licenses had been recently extended for an additional 20 years.

Giving up an operating license for a nuclear power plant in the United States is a permanent choice with implications that run into the many billions of dollars; there has never been a situation where a plant owner gave up an operating license and was subsequently granted another license to operate that plant.

The closest precedent available is the Tennessee Valley Authority's Browns Ferry. All three units were shutdown in 1985, each was later restored to operating status (1991, 1995, and 2007). The difference at Browns Ferry was that the owner (TVA) never gave up the operating licenses.

Unfortunately, there are several aspects of current rules that discourage nuclear plant owners from choosing to mothball plants.

There are only two license choices available for the owner of a nuclear power plant. The owner can maintain an operating license, which costs a minimum of $4.4 million per year in fees to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, or the owner can choose to give up the operating license for a "possession only" license. That costs just $231,000 per year, plus the cost of any additional regulatory services, which are billed to licensees at a rate of $274 per staff hour. (Note: Some operating licensees pay more than the minimum because they have special conditions that require additional regulatory services. If that is true, those services are billed at the same $274 per staff hour rate.)

In addition to the annual operating license fee, a company that seeks to maintain an operating license must maintain a certain level of staff proficiency and must maintain a security force sized to prevent a design basis threat from gaining control of the facility and causing the plant to release radioactive material. Of course, a plant that is in a state of semi-permanent shutdown could probably make a successful case for maintaining a substantially reduced staff compliment; there might already be a reduced staffing precedent available from the long-term shutdown and eventual restoration of TVA's Browns Ferry.

The owners of a plant that is being held in a semi-permanent shutdown state could also make a good case to the NRC that they should be allowed to defer any required investments in new capabilities until such time as they decide that they are going to restart the plant. A semi-permanently shutdown plant would not need to purchase any new fuel or pay any additional contributions to the nuclear waste fund; those contributions are based on the amount of nuclear electricity generation.

However, during any period of semi-permanent shutdown, a nuclear plant will be consuming days of potential operation; nuclear plant operating licenses are issued on a strict calendar basis with no ability to reclaim days. Even if there is no stress or strain put on any plant components because the plant is shut down and cooled down, the calendar keeps turning pages. Owners are logically reluctant to keep up the spending on a plant that might only have a few years of life remaining after the market finally turns around.

Without access to the detailed financial analysis used by Dominion and Entergy to determine that the best course of action was to permanently shutdown Kewaunee and Vermont Yankee, I have to make an educated guess about the considerations that drove their decision. It seems highly unlikely that the operating license fee difference was enough to cause utilities to give up an asset whose replacement cost would be at least $3 billion-$5 billion. The ongoing personnel costs might have been high enough to tip the balance, but I doubt it.

I got a hint in a Bloomberg article about Entergy's decision to shut down Vermont Yankee.

The reactor was expected to break even this year, with earnings declining in futures years, the company said. Closing it will increase cash flow by about $150 million to $200 million through 2017.

(Emphasis added.)

That's right. Entergy has determined, and announced to the investment community, that closing down a production facility that produces about 4.8 billion kilowatt hours of electricity each year using fuel that costs just 0.7 cents per kilowatt hour will result in a substantial improvement in their cash flow. That is true even though the plant will not be producing any product and even though the company will incur some transition costs.

The jewel for Entergy is that the owner of a plant in a decommissioning status has access to the decommissioning fund that was set aside at the time that the plant was built and received additional funds over the years that the plant operated. In the case of Vermont Yankee, the decommissioning fund balance is $582 million. Tapping that fund will allow the company to book more revenue.

There is one more factor that is probably more important for Entergy than it was for Dominion. Removing production facilities in a market that is suffering from low prices as a result of insufficient market demand is a tried and true strategy for commodity suppliers. If enough production facilities stop producing the oversupplied product, it will enable the remaining facilities to raise prices to a more profitable level.

Since Entergy has a number of other facilities that sell into the Northeast U.S. electricity market, it will benefit when those price increases happen. Since Dominion's Kewaunee was its only facility in the Midwest, it is hard to see any direct benefit to Dominion in the form of increased market prices.

I hope that your reaction to reading this explanation is to start thinking about ways to change the situation, before we lose any more emission-free, reliable, low-cost nuclear electricity production facilities.

Kewaunee Power Station

______________________

Adams

Rod Adams is a nuclear advocate with extensive small nuclear plant operating experience. Adams is a former engineer officer, USS Von Steuben. He is the host and producer of The Atomic Show Podcast. Adams has been an ANS member since 2005. He writes about nuclear technology at his own blog, Atomic Insights.

-3 2x1.jpg)