As a population, we are getting older. Globally, the number of people over the age of 65 is projected to almost double by 2050, from 931 million to 1.6 billion.

As we age, we develop a more practical appreciation of what life extension entails. We make individual choices—to work out, eat better, and maybe get that knee replacement. We are forced to consider what we are willing to spend and endure to get the results we want. Eat less processed food? Absolutely! Give up that glass of red wine with dinner? Not so fast! We are also better at recognizing the gifts—and the limitations—of our genetic inheritance.

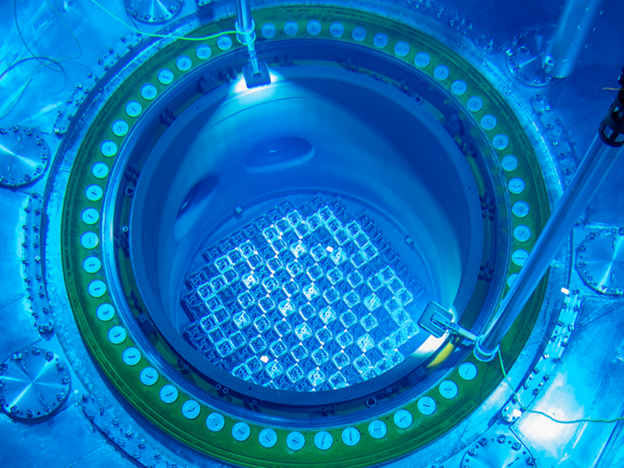

All of this puts the issue of subsequent license renewals for America’s nuclear plants in a much better public light.

I’m old enough to remember when the discussion of “life after 60” for U.S. nuclear plants first emerged in Washington. Suffice to say, the initial reception from policymakers was, well, guarded.

But a lot has changed since then. Today, we are not only extending the life of operating plants, but we are also bringing nuclear plants back from the dead to meet our nation’s newly voracious appetite for energy. There is no good reason to believe that there isn’t some subset of the current fleet that can go beyond 80 operational years.

Klaus Obermeyer is a legend in the skiing community. During WWII, he escaped Nazi Germany on skis, making it to Switzerland despite suffering a gunshot wound and a broken leg. After the war, he relocated to Aspen, Colo., where he worked as a ski instructor and eventually founded his eponymous ski apparel and equipment company. Among his long list of inventions are the quilted down jacket and the modern two-piece ski boot. He skied regularly into his 90s and is still alive—and heading into the office daily—at 105.

We can’t all be like Klaus Obermeyer. Our individual genetic inheritance and life circumstances play a large role in our longevity, for better or worse. But just as there’s no good reason to limit our own life’s expectations to a specific expiration date, there is no good reason to believe there isn’t at least some healthy number of plants in the current nuclear fleet that can operate beyond 80 years.

Whether humans or nuclear plants, age really is just a number, one that can be indicative, but should never alone be dispositive.