Document to preserve Swedish repository information across generations

The preservation of records, knowledge, and memory is recognized as an important component of nuclear waste management, preventing future generations from unnecessary interference with a waste repository and supporting future societies to make informed decisions about such sites.

Along those lines, Sweden’s Linköping University has created a 42-page booklet called the “Key Information File” (KIF) aimed at preserving information on nuclear waste as the country prepares to build a geologic repository for its spent nuclear fuel next to the Forsmark nuclear power plant.

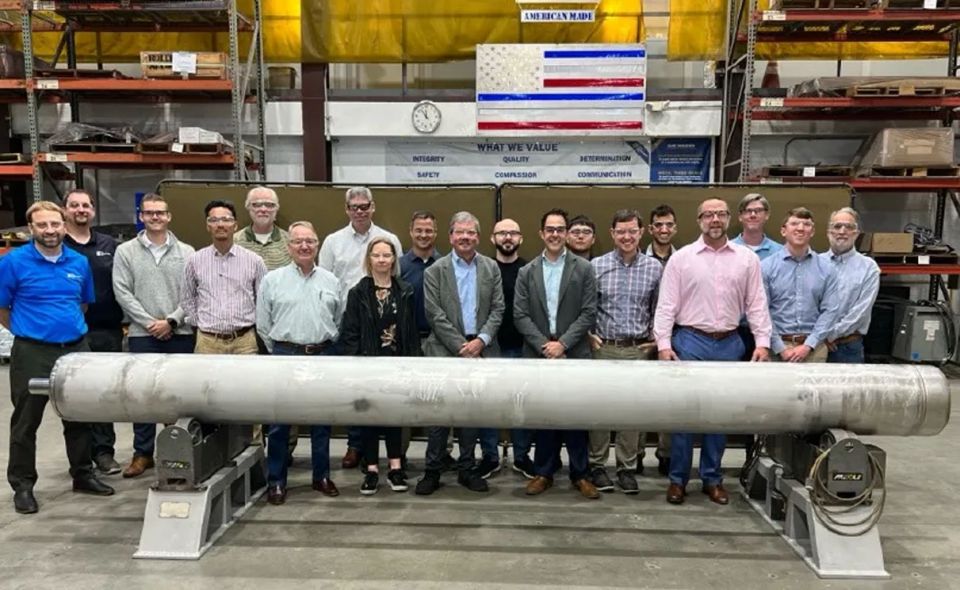

In January, the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, or SKB) announced that it broke ground on the Forsmark repository, which is planned to hold 12,000 metric tons of spent fuel in bedrock to a depth of 500 meters (1,640 feet). SKB expects the final repository will be ready for disposal in the 2030s.

KIF: According to the university, the KIF document, produced on behalf of SKB, contains the most important information that a future reader may need about the Forsmark repository. Currently available only in English, the booklet is divided into three parts: summary, critical information, and instructions for the future.

“We’re trying to do something that no one has ever done before. The person who eventually reads this might not even be human, but perhaps a kind of AI or something else,” said postdoctoral fellow Thomas Keating, who led the research project with Professor Anna Storm at Linköping University.

According to the university, the KIF document is the result of three years of work in which the researchers collected opinions from many sources: young and old, experts, and the public. The work is part of an international initiative in which several countries, such as France and Switzerland, are working on similar documents for their final repositories.

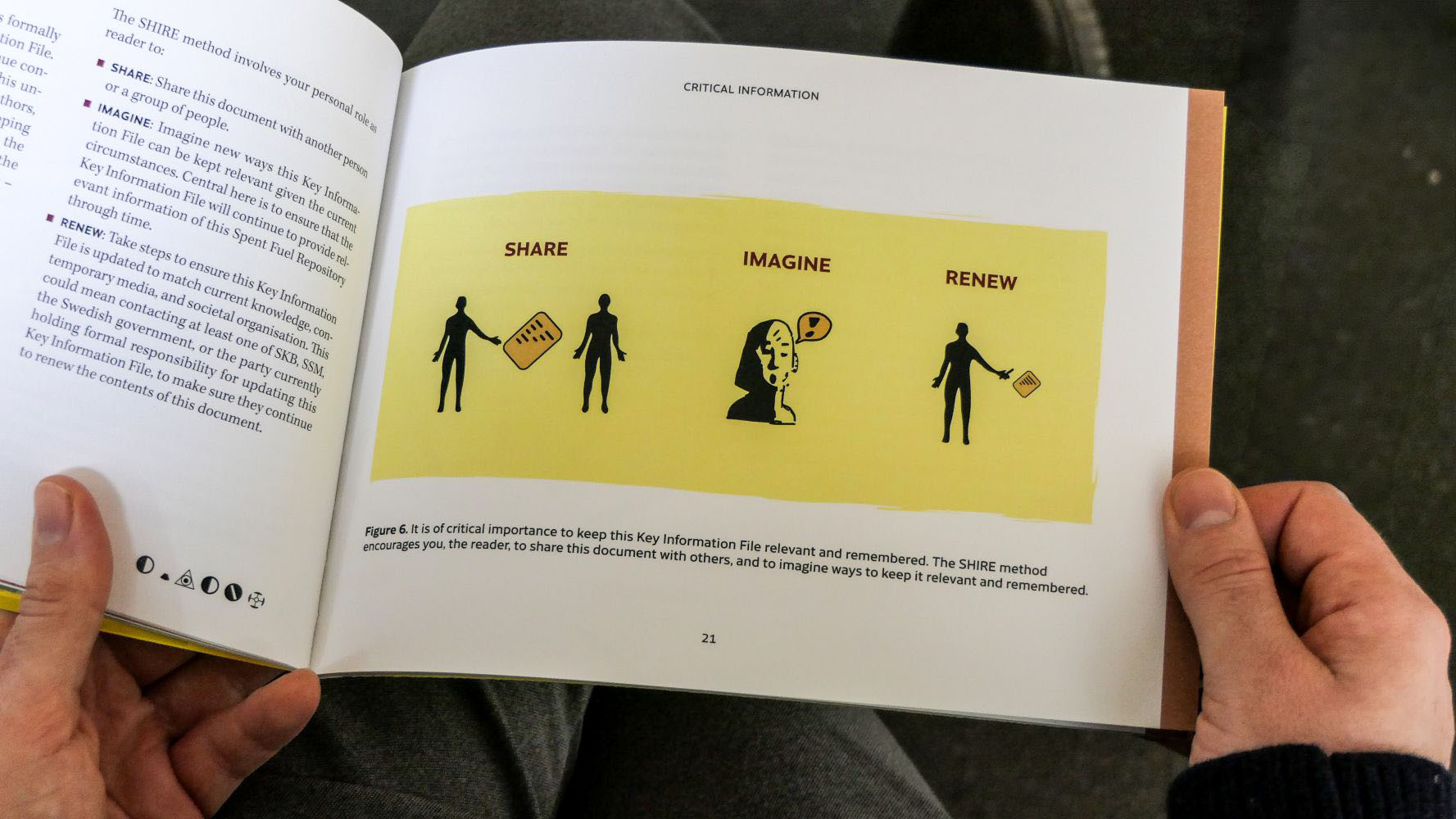

SHIRE method: In writing KIF, researchers tried to create a document that will entice the reader to reread it and share it with others, according to Linköping University. Professional illustrators were hired to make it aesthetically pleasing, and while the text is easy to understand, there are mysterious characters on the cover—a coded message for the reader to try to solve. Through playfulness, the researchers want to create curiosity and enthusiasm.

Language, however, changes over time, as does the interpretation of images and symbols. The document therefore tasks future generations with updating the information and transferring it to new storage media if necessary. It also provides suggestions on how knowledge can be kept alive, for example, by including it as a subject in school curricula or creating stories and other cultural expressions around it.

The researchers have named this method SHIRE (share, imagine, renew). It is an invitation to the reader to share the content and become actively involved in figuring out how it can be renewed so as not to be forgotten.

Preservation: The researcher team has proposed that the KIF document be updated every 10 years, but it is not yet clear who will be responsible for this in Sweden. For now, the idea is that it be kept at the Swedish National Archives.

In addition, Linköping University said that it has already been decided that the document will be part of the major archiving project Memory of Mankind. Founded in Austria in 2012, the Memory of Mankind archive aims to preserve humanity’s collective knowledge for posterity on material that will last for thousands of years.

“So it will be printed on ceramic tablets and placed in an old salt mine in a mountain in Austria,” said Keating.