Collaborative R&D Effort Buttresses Hanford Vitrification

An international team of researchers have collaborated to reduce operational risk and realize a vision of long-term success for the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant (WTP) at the Department of Energy’s Hanford Site near Richland, Wash.

For over a decade, the DOE’s Hanford Field Office (HFO) has been working with national laboratories, universities, and glass industry experts to establish capabilities and generate data to increase the confidence in a successful startup and transition to full-time operations at the WTP.

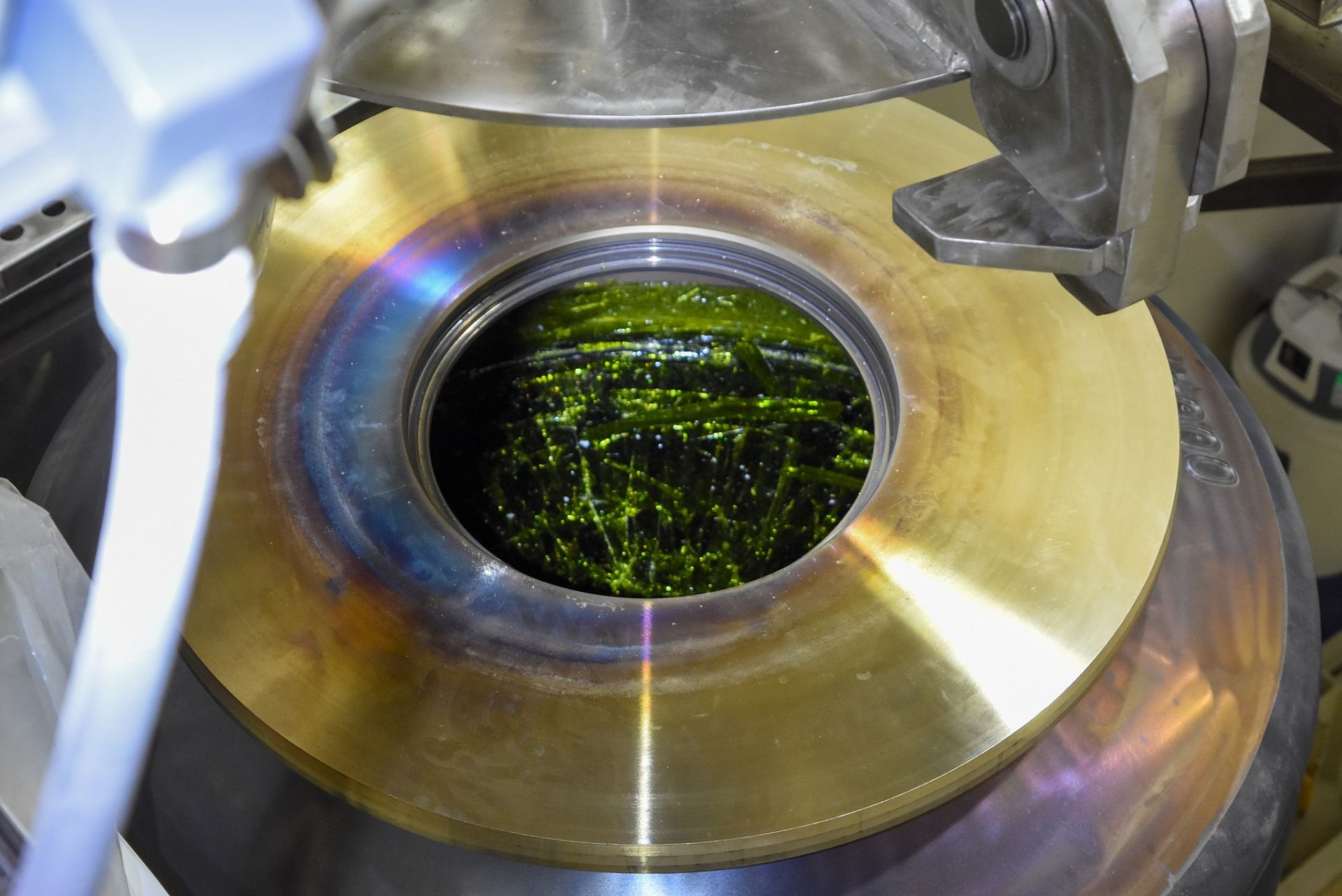

A container of test glass is poured at the Low Activity Waste Facility in 2023. (Photo: DOE)

Vitrification is the process of incorporating the waste into a durable glass structure. The waste components do not sit inside the glass, like water swishing in a bottle. Rather, they become part of the “bottle” itself, atomically bound in place until the glass dissolves.

The 56 million gallons of chemical and radioactive waste stored in the underground tanks at Hanford are partially analyzed to confirm they meet minimal acceptance criteria for treatment as either low-activity or high-level waste. The treatment standard set forth by the Environmental Protection Agency and responsible parties for issuance of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act operating permits for low-activity and high-level wastes is vitrification.

Once the waste is staged for treatment at the WTP, more detailed analyses are performed to fix the amounts of glass forming-chemicals that will be added to make feed that will produce acceptable glass for disposal while remaining within the limits of operating the melters. Two of the more important such limits include the electrical conductivity of the melt (melting is accomplished by electrical resistance heating) and the viscosity of the melt (flow property of a liquid important for moving the glass out of the melter).

By having a small-scale mockup of the WTP, the HFO Enhanced Waste Glass Program hopes to collect experience allowing the transition from commissioning to full operations to minimize unanticipated events, such as when unexpected components are found during the final chemical analyses when the waste arrives at the WTP.

These components could present a need to monitor the melting process more closely. They include chemical species that could cause slower processing rates; generate greater or lesser quantities of gases that are part of the melting process, starting with drying of the feed as it is injected into the melter; and thermal destruction of the host of salts that generate carbon dioxide, nitrogen gas, nitrous oxides, etc.

Considerable resources are appropriately focused on completion and startup of the WTP facilities. However, the history of starting up vitrification plants around the world is instructive in anticipating process engineering and plant operations challenges to immobilize very chemically diverse wastes with all their associated variations in physical properties (i.e., liquids, salts, and sludges).

The HFO Enhanced Waste Glass Program is a comprehensive program designed to anticipate and address current and emerging challenges that may have a low probability individually, but collectively can impact success greatly. By investigating glass science for application to waste treatment, we enhance the flexibility to accommodate any anticipated tank waste stream needing treatment, doing so in a facility that exists and is in operation, by a simple and established variation of the glass forming-chemicals added while establishing greater treatment efficiencies for the WTP.

The Vitrification Off Gas Rig (VICTOR) in the test facility at PNNL is a simulant test platform designed to generate representative melter off-gas and have flexibility to test performance of various off-gas components and configurations. (Photo: DOE)

Separating waste streams

The WTP mission for treating the discharges of 45 years of plutonium production at Hanford is meant to address two major waste streams: low-activity waste and high-level waste. Historically, Hanford has managed the tank waste as high-level. The definition of “high-level waste” was tied to DOE O 435.1, “Radioactive Waste Management,” which mirrored the Atomic Energy Act (1954) and Nuclear Waste Policy Act (1982) definition of the term “high-level radioactive waste” as:

(A) the highly radioactive material resulting from the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel, including liquid waste produced directly in reprocessing and any solid material derived from such liquid waste that contains fission products in sufficient concentrations; and

(B) other highly radioactive material that the [Nuclear Regulatory] Commission, consistent with existing law, determines by rule requires permanent isolation.

In the 1990s, a series of exchanges between the DOE and the NRC established the understanding that a low-activity fraction of the high-level waste could be separated by certain unit operations. This understanding allowed for the conditioning of tank waste by filtration and ion exchange to separate 95 percent of the volume of the reported 56 million gallons with 5 percent of the radioactive components left.

The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, closest to WTP and directly connected to the Hanford Site, has been the integrator of this effort, maintaining the largest number of knowledgeable staff, a diverse list of laboratory equipment, and several key process testing platforms.

Hanford’s waste inventory possesses nearly every element on the periodic table of elements. All but a few of the greater than 200 elements on the table are present in the tanks. Expanding the acceptable glass composition region is key to reducing immobilization costs and improving waste loading.

Multiple laboratories including the Vitreous State Laboratory, Savannah River National Laboratory, and PNNL, have facilitated development of a massive database of glass properties from which PNNL has built property-composition models and a glass formulation algorithm to run the WTP’s Low-Activity Waste Facility more efficiently.

The physical properties of a glass are the result of contributions of each component of a formulation to any particular property. Some of the chemical species have a meaningful contribution to a specific property (e.g., viscosity, electrical conductivity, wear of the melter refractory, and heat capacity), while many might have little to no influence on a property controlling the making of a good glass waste form.

The WTP facilities with melters are operated by the models of formulation components and their influence on the glass properties. The model is used in concert with the algorithm that enumerates all the hard constraints or bounding operational limits of the facility. A formulation for a glass is calculated based on the analysis of a batch of waste. The formulation is analyzed by the algorithm to ensure that no plant limits are violated or that no operational limits are at the edge of the specified range of the individual limit.

Understanding the structure of glass and how the structure controls the physical properties is fed back so as to inform the empirical data collection. Investigating the behavior of challenging waste chemical components in the feed stream helps define how to model the relationships controlling the efficiency of treatment. Fundamental work in this area is being carried out at Rutgers University, Sheffield Hallam University in the United Kingdom, and Washington State University.

The diversity of Hanford’s waste also challenges steady vitrification operations. The melter feed makeup affects the processing rate, evolution of conversion gases, and retention of volatile components.

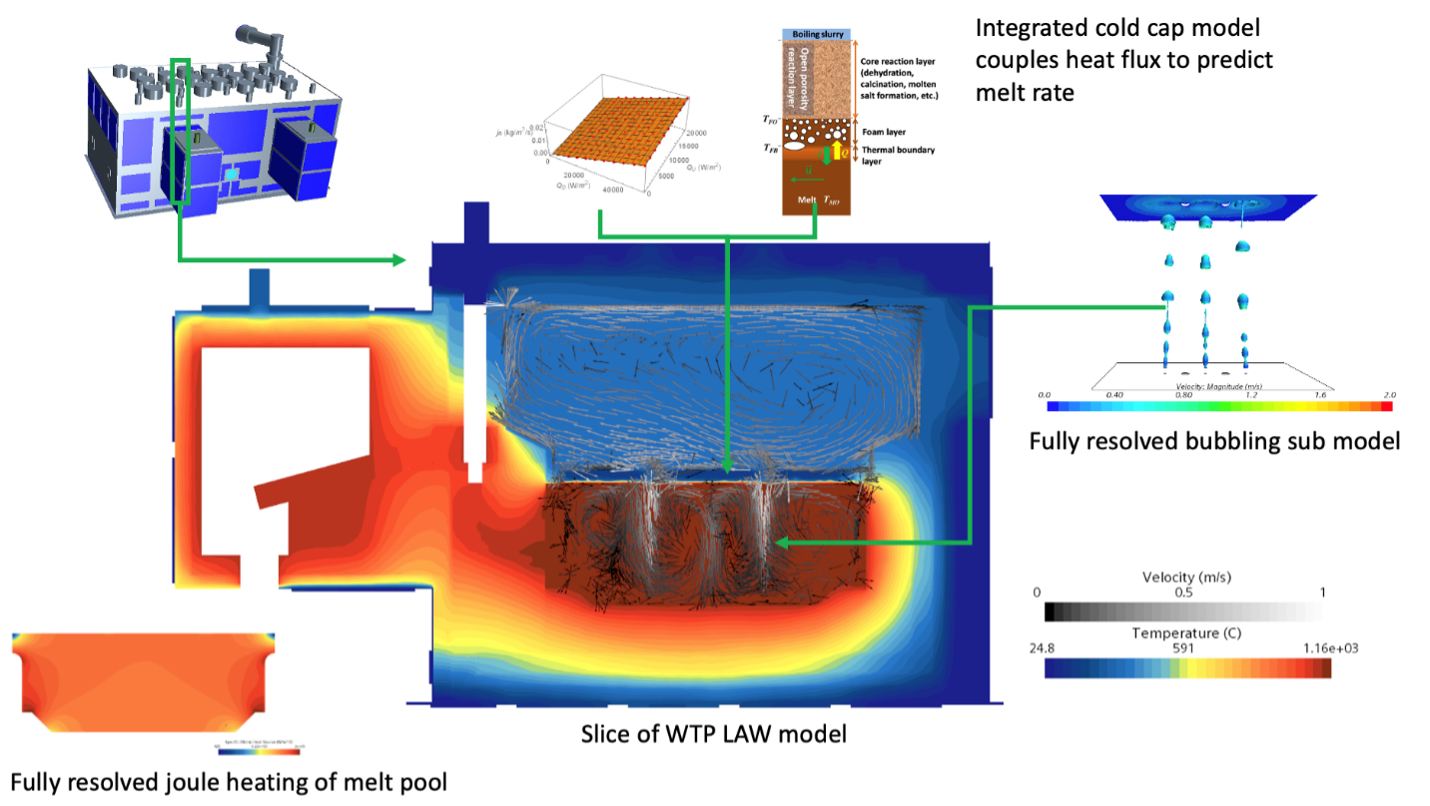

Diagram of integrated melter model: depiction of the integration of multiple submodels (e.g., heat transfer between the melter electrodes, heat transfer by bubbling, heat transfer from the pool of molten glass through the cold cap, and heat loss through the refractory) into a computational fluid dynamics simulation of the WTP Low-Activity Waste Facility melter. (Image: DOE)

The melter feeds are characterized by a set of simple laboratory tests at PNNL and the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague. The characterization tests typically include the determination of water content in the feed, thermogravimetric analysis to evaluate mass loss during heating, evolved gas analysis to determine quantity and composition of conversion gases as functions of temperature, differential scanning calorimetry to measure the enthalpy of conversion reactions, feed expansion test to assess the temperature intervals in which the primary foams evolve and collapse, and X-ray diffraction to determine the amounts of crystalline phases as functions of temperature and estimates of the viscosity of the amorphous phase.

The gathered data allows for the development of models and correlations for the feed-to-glass conversion process. The feed is a slurry of well-mixed components from the waste tanks and the proper amounts of each of the 13 glass forming-chemicals added to the waste at the WTP. The suspension is added through the lid of the melter onto the pool of molten glass already in the melter. The heat from the molten glass rises through the solid feed floating on the top. The floating island of feed is called a cold cap, or in commercial glassmaking, the batch blanket.

The tests were designed to provide a fuller understanding of the cold cap region, or the region of slurry-to-glass conversation above the melt pool—the region in which all the chemical reactions take place to decompose the chemicals in the feed that cause the gas-producing reactions and the creation of the chemical bonds that make glass. Models of the response of the feed to the supplied heat through the cold cap have been incorporated into well-established mathematics of computational fluid dynamic representations of the WTP melters.

Once established, the representations have been validated against the data collected at the range of scaled melter runs performed for the last two decades of work supporting the WTP. The scale melters used to support the design of the WTP melters benefited from an extensive temperature gathering capability all through the pool of molten glass, the region above the molten glass, and out through the melter lid. The computational fluid dynamics work is carried out by Idaho National Laboratory at their powerful computing center using creative simplification techniques to incorporate detailed submodels into the integrated melter simulations. Fortunately for the WTP, these are the same resources brought to bear on the understanding of heat transfer needed for the design of nuclear reactors.

A solid product

The VICTOR control station at PNNL. (Photo: DOE)

A primary objective of the vitrification process is to produce a durable waste form. As is said, the proof is in the pudding, and for Hanford’s glass, it is how durable and resistant it is to the effects of aging in the disposal facility.

Hanford imposes tests that aggressively age the glass in a short period of time (i.e., one to two weeks) at excessive temperatures to accelerate the loss of integrity. Additional tests are used to model the release of components of concern from the glass and subsequent migration through the environment over hundreds of years.

Incorporating the components of the waste stream into the glass network provides for a stable solid, ensuring the radioactive components are trapped and not released into the environment at an unacceptable rate. Therefore, significant effort has been dedicated to understanding and documenting glass durability with respect to waste and melter feed chemical variability.

Many laboratories have completed traditional waste glass corrosion testing, such as the product consistency test on simulant glasses from crucible melts to document corrosion for various compositions. In preparation for testing the corrosion of WTP commissioning and operational glasses, PNNL recently completed a side-by-side comparison of low-activity waste baseline simulant and radioactive glasses. The glass samples were produced in scaled melter systems using simulant and actual radioactive waste according to the baseline glass formulation algorithm.

Vanderbilt University, the University of Sheffield in the U.K., and PNNL have been evaluating standard EPA test methods for waste glass durability. Colleagues from Sweden and Israel have facilitated comparisons between waste glass durability and analog glasses that have existed in the environment for thousands of years.

Simply treating waste by making glass limited by a demonstration plant is not in the best interest of working off the inventory of waste in the shortest amount of time. The desire is to significantly enhance the capacity without creating the need for retrofitting an operating nuclear facility. Therefore, being able to fully understand the byproducts that will leave the melter environment and require trapping for recycling into the melter, or be sent to a secondary waste treatment facility, is needed to be able to introduce advances of the chemistry of the treatment process.

Creating this capability to predict and anticipate such components and their quantities is the purpose of the Vitrification Off Gas Rig (VICTOR) at PNNL. The unit starts with a melter that was designed to be exactly to scale of the WTP melters (for example, gas residence times and bubbling of the melt), but has the benefit of the off-gas train. That is to say, the best features of VICTOR are the off-gas components that mimic the off-gas treatment capabilities of the WTP’s Low-Activity Waste and High-Level Waste facilities.

Following the concept of “plug and play,” the flow of gas from the melter can be directed through a system that is a small-scale operation of either of the two treatment facilities. Capturing and analyzing the materials that are not participating in the formation of the durable glass network will inform and project the needs or secondary treatment capacity to deliver a comprehensive waste treatment mission.

Equipment performance

The performance of key materials is essential to the success of plant equipment and the vitrification process. In the absence of a full understanding of the wear of the refractory bricks and metal components in contact with the molten pool of glass and waste feed, the projected maintenance schedules, by necessity, must be conservative. In-service failures might well be catastrophic, while the needed conservatism greatly underestimates a useful lifetime.

Knowing how each recipe of glass for each batch of waste will age, the refractory and metal components will inform the operator as to when:

To best prepare the next $35 million melter or bubbler system for procurement actions.

To anticipate the six-month loss of production for a melter changeout.

To mobilize the other contractors for transportation and disposal of spent components.

Staff at PNNL, SRNL, the University of Chemistry and Technology, and INL are refining test methods and gathering data to better understand and be able to predict the glass composition and operations impacts on melter refractory and metal melter component life. In the off-gas treatment area, staff at University of Nevada-Reno are developing unique materials to successfully capture iodine.

Frequent and meaningful interaction with renowned staff from industry, government agencies, and universities have benchmarked this work against the state of the art in glassmaking with nuclear safety standards overlaid on the industrial safety requirements.

Communication with the glass company Corning ensures alignment with cutting-edge industrial glass manufacturing developments. Comparison of methods and results with the Czech Republic company Glass Service ensure modeling techniques meet the latest advances.

Discussions with counterparts at Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives (CEA) in France, as well as at the Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry in Japan, ensure parity with similar applications of research, where technologies, waste streams, and immobilization strategies are slightly different.

Continued success

The WTP has long been described as a first-of-its-kind and largest treatment facility in the world. Many of the performance standards and operational requirements imposed upon the WTP contractor were set in the mid-1990s. As such, the HFO Enhanced Waste Glass Program found its origins in the need to respond to the mission projections modeled in baseline documents produced.

These projections advanced the need for second facilities twice as large as the ones being designed at the WTP. Such facilities may require further treatment capacity, as missions lasting more than 100 years would necessitate additional capital construction in the near term.

If the government is to be successful at the WTP, it remains apparent to decision makers that flexibility and capability beyond the narrowly defined definitions for performance in the operator’s contract yield significant value. Starting full-scale radiological operations at WTP while being reliant upon limited sources of minerals for glass-former chemicals and absent of fully understanding how mineral variations will influence melter operation is shortsighted and presents unnecessary risk.

Through nearly three decades of design and construction, many of the chemical absorbents and commercial process chemical commodities have been taken off the market. The strategy of building a diverse technical team to better understand those challenges has also prepared resources that stand ready and have contributed to the resolution of issues that have arisen. Based on the history to date, additional challenges to the startup of the WTP and its long-term mission will emerge.

Albert Kruger is the Glass Scientist with the Department of Energy’s Hanford Field Office. This article accompanies Kruger’s article “Glass Strategy: Hanford’s Enhanced Waste Glass Program,” from Radwaste Solutions, Spring 2024.